On the night of July 20, 2002, Infinity Cat Recordings sprung to life by selling 11 copies of an album that hadn't even been made. Sure, their inaugural release had just been taped — live, for an audience of a few dozen at the long-since defunct Guido's Pizzeria. But the crude recording, made with a DAT machine taped to a back wall, hadn't been mixed, burned onto CDs or slipped into the photocopied sleeves that the band members would later hand-splatter with paint.

Selling records is sometimes referred to as "moving units." But in this case there were no units. And Tusky Mahloo by The Sex (ICR-01) wasn't an album so much as the promise of an album. In much the same way, Infinity Cat wasn't a record label, really, nor were the baby-faced brothers Jake and Jamin Orrall — then just 16 and 14, respectively — the electrifying, continent-hopping band they would eventually become. They were a pair of high school kids growing up on the West Side whose basement lair was as cluttered and chaotic as any teenager's hangout. Only theirs was heaped with stashes of experimental recordings and teetering towers of one-off music projects.

But the people who paid $5 that night, to have a just-recorded debut album by a trio of teens mailed to them whenever and however it was finally manufactured, did so because they believed one thing: Whatever the particulars of the finished product, it was going to be good.

And as The Sex became JEFF became JEFF the Brotherhood — a hard-touring duo with sold-out shows from Brooklyn to L.A. and a major-label record deal that's just kicking in — fans of the scrappy record label the brothers started out of their parents' basement a decade ago have continued to snap up just about anything they release for that very same reason. Jack White is often credited, and rightly so, with helping expand and deepen Music City's reputation. But long before Third Man opened its doors on Seventh Avenue, Infinity Cat had already become the heart through which Nashville's punk-rock arteries pumped their noisy, vibrant blood — helping make the city synonymous with a raw, restless strain of rock 'n' roll, and doing it on almost no budget.

How they got to where they are now is a story that could really only happen, at least the way it did, in Nashville.

A few blocks from Greer Stadium in the Wedgewood-Houston neighborhood, along a fairly unremarkable side street, sits a neat eggplant-colored house. A small etched metal sign beside the back door displays the company logo — a simple line drawing of a cat with a figure-eight floating halo-like above its head — but otherwise the low-slung ranch blends right into the neighborhood, a mix of single-family homes and commercial properties that includes nearby Gabby's Burgers and Fries.

Most days you can find Robert Ellis Orrall here, starting early in the morning and often late into the night. Although Jake Orrall is Infinity Cat's de facto CEO — no one has official titles — and makes the final decisions about releases, Bob (as most people call him) is the label's de facto general manager, answering emails, directing the staff, printing out orders and album one-sheets — sometimes all at once, while also fielding a reporter's questions across a counter that separates the kitchen from the business/songwriting/recording/chilling-out area, shouting over his shoulder as he stocks the fridge with sodas and flavored seltzer. With Jake on tour with JEFF the Brotherhood much of the year, managing the day-to-day operations falls to Bob. Not that he minds too much: "I love coming to work here every day," he says, beaming.

If you've ever promised yourself you'll never grow up, Bob Orrall is the kind of person you want to not grow up to be. On the wall above a desk that holds an iMac, a set of studio monitor speakers and a small bank of audio equipment, there's a large framed plaque commemorating 3 million copies sold. It's for Taylor Swift's eponymous debut, for which Orrall co-produced or co-wrote a total of six songs.

A few feet to the left hangs a bright orange Super Soaker water gun. Bowls of candy, antique toys, musical instruments, paintings, records, magazines and pieces of old cars litter the room, and a Daisy Red Ryder BB gun hangs from a window frame.

"I love the possibilities," he says. "I love hearing these kids making this great stuff. I feel real lucky."

Luck can be important. Part of the reason Infinity Cat is one of the few labels that can directly upload tracks to iTunes is that early on, Bob and Jamin crashed a party held to recruit labels for the new iTunes store. The kitten-size Infinity Cat hadn't made the highly exclusive guest list, but Bob feigned disbelief at the omission. Standing nearby, Jeff Walker of AristoMedia quickly caught on and played along with the ruse. Feigning outrage, he called Infinity Cat "one of the most important labels in town" to the unwitting Apple gatekeeper, who promptly waved the Orralls in.

The brothers say they don't hit up their dad for business advice very often. "A lot of Dad's experience, in that world, doesn't really translate," Jamin says. Likewise, Bob doesn't try to force his viewpoint — not that he could — and Infinity Cat is no shell corporation for his royalties. "There's no investment," he says. "I'm not putting money into this."

In 2010, Bob left Music Row, at least in the physical sense. For four years he had written songs, recorded demos and, in his spare time, helped run Infinity Cat out of the 1010 Music offices on Music Square West. In January 2011, he and the label moved to the house just off Chestnut Street. The relocation was not a big maneuver in itself, but soon after, as the steady climb of the label's flagship band began approaching some lofty peaks, things would begin to grow faster than anyone involved had imagined possible when they started.

"We were really inspired by Asian Man Records at the beginning," Jake says, referring to Mike Park's label out of Monte Sereno, Calif., as he reclines on a couch at the Infinity Cat house. "Just this guy putting out tons of punk records out of his mom's basement."

"And Dischord, obviously," Jamin adds from across a glass coffee table.

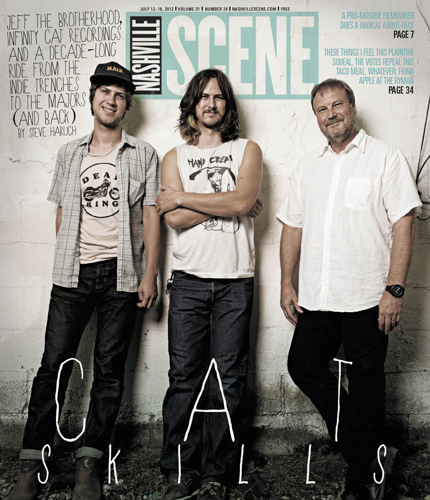

Jamin is the more talkative of the two, though neither is particularly talkative, at least around media types. Even offstage, Jake cuts an imposing figure, with his broad shoulders protruding assertively from under long locks of hair. While Jamin has caught up in height, he still looks every bit the younger brother. When the two interact, often in short, terse phrases, it sometimes seems there must be a telepathic connection filling in the gaps. Theirs is a bond strengthened by years of playing music together almost every day. Online haters have tried to characterize them as spoiled showbiz kids who never paid their dues, but don't believe it for a second: In their mid-20s they've already logged a lifetime's worth of shows — in living rooms, mostly empty clubs, dingy pizzeria basements and most recently, on a barge in the Pacific Ocean during a surfing competition.

"We were listening to a lot of Fugazi at that point," Jamin recalls. "And any punk band that came through town, any show we could go to, we'd buy as many records as we could afford. We'd take them home, look at the labels and order stuff through the mail."

Like many of the record labels they admired — often little more than names devised and slapped onto records to lend them some air of importance — Infinity Cat started as an outlet for Jake and Jamin to release their own music and their friends' music, with few ambitions beyond that. The purpose at first was to put whatever money they were able to make into their next release. If they liked a band, they'd put out a record if they could afford it.

"We're still at the same point," Jake snorts.

But running a relatively small operation lets Jake be nimble. According to Seth Riddle, general manager of Serpents and Snakes Records, the imprint owned by Kings of Leon, "The key for small labels [like Infinity Cat] is they react really quickly. They get things done." And that spontaneity is an asset.

Case in point: During a recent break from touring, Jake asks Jamin about taking some copies of their new single, a split 7-inch of Hole covers with the band Hell Beach, and making special tour-only sleeves for them. Although Jamin long ago relinquished his responsibilities — "I realized I don't want to run a record label," he says — he still acts as a sounding board for his brother's ideas.

"You want to?" Jake asks.

"Sure," Jamin answers quietly.

"What did you do with the Third Man single? Just cut out the letters?"

"Yeah, just printed it off on the computer, cut the letters out and Xeroxed it."

"Let's do 150."

They'll almost certainly sell every one, and by making a version of the single that was only available on one tour, they've created another necessary acquisition for their rabid fans, who will post about it on "The Brohood" or other Internet forums. There, aficionados like JEFF superfan John Cosby might go hunting for a copy, perhaps offering another record variant or piece of band- or label-related minutiae for trade. Those limited-edition sleeves with the hand-cut letters, and the differently colored vinyl for various editions of a single, are all part of the label's quirky appeal for Cosby, who lives on a farm with his parents in Tattenhall, England — what he calls "a sleepy little village" of fewer than 2,000 people about 35 miles southeast of Liverpool.

"They understand the value of scarcity and DIY," says Jay Millar, marketing director for United Record Pressing, whose back door is just a couple hundred feet from the Infinity Cat house. On any given day you might see him guiding a hand truck laden with boxes of freshly pressed records down the street.

"I think they've done an exceptional job carving their niche," Millar says. "They've got a diehard group of fans that will pick up anything they put out, and it's not just blind allegiance ... it's good, and they've earned the trust of their fan base."

Cosby says he's lost track of exactly how many Infinity Cat albums he owns. Many are on loan to friends around the world who belong to record-swapping clubs formed online. "Apart from the killer music, the artwork is always brilliant," he adds. "A lot of the early releases came with handmade/hand-stamped artwork, giving every [record] an individual touch — you feel like you've got a one-off!"

Even with brand loyalty so fierce and so far afield, Infinity Cat isn't quite where Jake wants it to be. Over his shoulder, his father's eyes, decades younger, peer out from an oversized cardboard poster that sits behind the couch — a blown-up cover of Contain Yourself, Bob's 1984 album for RCA.

"For a label our size, it's all about being a cool label," Jake says, offering Mexican Summer — home to recent tour companions Best Coast — as one example. "We've just never been one of those."

He has trouble defining "cool" — "listened to by art school students," he jokes at one point — but he's sure it has eluded Infinity Cat to this point, even as influential outlets from Brooklyn Vegan to Vice dutifully announce every new JEFF video, every new tracklist, every new "unveiled" piece of album art.

Cool or not, the label landed on a 2010 Billboard list of the top 50 indie labels in the country, alongside art school mainstays like Matador, Merge and Jagjaguwar. Jenn Pelly, now a Pitchfork staff writer based in New York, compiled that list. "Infinity Cat might not be fashionable," she says, "but in my eyes they're pretty radical." Demurring on the whole notion of "cool," she says, "Infinity Cat and the bands on that label are probably what make me want to visit Nashville more than anything else."

For his part, Riddle — who moved to Nashville 16 days before Jake and Jamin collected their first preorders that night at Guido's — doesn't mince words: "They're one of the coolest labels in the country," he says firmly. Then, to drive the point home, he adds: "Fuck, man, those are my favorite bands — period."

[page]

On a recent afternoon, the I-Cat house is a hive of activity. Piles of promo CDs, scraps from recently cut record sleeves and other evidence of hand assembly occupy a table in the kitchen where Heavy Cream singer Jessica McFarland is hanging out. Ian Bush, a 20-year-old intern from Appleton, Wis., and a distant relative of Sugarland singer Kristian Bush, has just arrived. "I've only been here two weeks, and I haven't done the same thing twice," he says, "which is pretty sweet."

Ale Delgado is Infinity Cat's social media coordinator — i.e., the main tweeter and Facebook updater — and de facto webmaster. A 21-year-old Belmont music business major originally from Cincinnati, Delgado decided she had to work at Infinity Cat after talking to a former intern who said he'd spent an entire day spray-painting old cassettes. "That pretty much made the decision," she says. Delgado also runs the milkshake truck Moovers and Shakers in the summer with fellow Bruin Hayden Coleman.

"It's like hanging out with your family, but better than your regular family," Halle Ballard says of the loose, fun vibe the label has cultivated. "And [Bob] stocks up the fridge with mini ice cream things."

At 18, Ballard is somehow both the label's youngest employee and its longest tenured non-Orrall, though she likens working at Infinity Cat to being adopted. Headed to Belmont in the fall to join Delgado and Bush as a music business major, the Nashville native has been at the label for five years, ever since taking an internship on a whim, after a friend who had signed up for it turned out to be too young.

These days, Ballard is also the lead singer in Art Circus, one of Bob's projects and a vehicle for his more whimsical pop songwriting. (The Art Circus album Apples and Oranges is out on Infinity Cat's sister label, Plastic 350.) And she designed the newest Infinity Cat T-shirt, now in its second printing. This is not a particularly hectic day, but it's busy enough that when local photographer Emily Quirk calls to see if there's any work she can do to pick up a few hours' pay, Bob gives the green light.

"When I first started here, I'd do like three orders every couple days or something, and the rest of the time I would just hang out and watch Bob write songs," Delgado says. "And all of a sudden I remember I came in one day and there were so many orders, and there was nobody else working at the time so I had to do them all myself. It was crazy. We blew up really fast, pretty much out of nowhere."

Or maybe not out of nowhere, exactly. On Delgado's first day of work, JEFF the Brotherhood had just finished recording their sixth album, We Are the Champions. "It was just cool because I got to see that whole thing happen," she says. By "that whole thing" Delgado means JTB's signing a deal with Warner Music Group, through which Champions is distributed by the conglomerate's sizable Alternative Distribution Alliance. She also means that thing where the preorder link for Champions went live and almost immediately crashed the Infinity Cat website — which led to that thing where the site finally came back online, but a glitch in the system made it impossible to limit the number of orders, so they ended up selling almost 300 more than they had planned for. "And people can still buy it — it's really weird," Delgado says. "We should probably fix that."

Champions was JEFF the Brotherhood's first album with Warner, though you could be forgiven for not noticing that aspect of the release. Warner sent out no official press release, and there is no Warner logo on the album sleeve. Aside from a catalog number on the spine, there is no evidence that Champions has anything to do with Warner at all. In fact, even as the final details of the deal were being ironed out, Infinity Cat pre-emptively released Champions themselves, and the band took a limited edition clear vinyl version with them on the road.

"The album was done," Jake recalls matter-of-factly. "Things were moving too slowly for us."

It was a gutsy move (or suicidal, depending on your viewpoint) to potentially jeopardize an unusually sweet and artist-friendly deal with one of the world's biggest label groups. But Jake and Jamin are no strangers to following their gut. Besides, they didn't need a record deal. They already had one — with themselves.

In the end, everything worked out, and future albums — including the new Hypnotic Nights, due July 17 (see review on p. 33) — will be released under the Warner/Independent Label Group umbrella. The band demanded full creative control, and they got it.

"Labels have been after them for years," Riddle says. "But they waited for a deal that made sense." As someone who's tracked the band's progress, Riddle admires the approach they've taken — not signing to a larger indie, not taking on too many support roles for better-known acts. "If you're gonna build a big house, you've got to build the foundation right," Riddle says. "They've been very diligent and taken the right steps. They are ready to be a big band."

A highly sought-after band on its roster inking a deal in the record-label big leagues and seemingly poised to become stars? Infinity Cat has been here before.

Not far from the railroad tracks that run just beyond the Nashville Sounds' guitar-shaped scoreboard, and a stone's throw from the Infinity Cat house, sits another notable, if unassuming, property: producer Roger Moutenot's studio.

It was here that Moutenot, who's worked with the likes of Sleater-Kinney, Paula Cole and Yo La Tengo, served as recording engineer for Infinity Cat's 17th title, an EP released in 2005 called Damn Damn Leash — seven minutes and 25 seconds of unhinged punk 'n' roll that blew out of the speakers like a tornado with a mile-wide sneer. It introduced Nashville, and later the world, to Be Your Own Pet, one of the most compelling and polarizing bands ever to call Music City home.

You can't really talk about Infinity Cat without talking about Be Your Own Pet. You also can't really talk to Jake and Jamin about Be Your Own Pet, a band they're both happy to leave in the past — or at least their roles in it. Jake had already left BYOP, and the country (for a year abroad in Iceland), by the time those first seminal tracks were recorded. But it's Jamin lashing the drums behind Jemina Pearl's snarled vibrato and Jonas Stein's careening guitar stabs.

It was a band made up of kids whose parents had served in Music Row's trenches, in one capacity or another. But the BYOP kids weren't your typical sign-me-up-for-corporate-band-camp types eager to be fitted with whatever haircut was selling best that week. "Everyone in that band is so talented, and so smart," Riddle remembers thinking. "They're hard-working, unusual in all the best ways — you just knew that whatever happened, they would have interesting careers." They were destined to blow up, and everyone knew it.

"They would have been the American Arctic Monkeys," Riddle says.

At the time, Riddle worked for Rough Trade, which later released Damn Damn Leash in the U.K. He would eventually put it in the hands of legendary BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel, who quickly played it on his show, conferring it with his estimable approval. Britain's taste-making music press picked up the drumbeat, and major U.S. publications followed suit.

From that point on, it's hard to overstate the fervor — both laudatory and hostile — that surrounded this group of preternaturally charismatic teenagers for the short time their flame burned impossibly bright. The band became a beacon for those hoping to awaken interest in Nashville's non-country music scene, and a resentment magnet for those who saw the band as proof of everything wrong with contemporary music's youth obsession and trend-chasing ways.

"Then the majors came calling, and it got weird," Bob Orrall recalls. At one point, as label headhunters took turns courting the young band over fancy expense-account dinners, Bob saw a familiar face: Seymour Stein, the A&R rep who had tried to recruit him to Sire Records 25 years before. "Do you know you're trying to sign my son?" he asked, the layers of his life suddenly collapsing around him.

Eventually it was on to XL Recordings for the young rockers, and their faces on magazine covers, their names on music blogs and all the attendant pressure to play the major-label game. In the middle of it all, with everyone's star seemingly on the fast-track to fame, Jamin quit the band.

"It wasn't what he signed up for," Bob says.

Riddle remembers watching the teenage band as it buckled under the pressure — including battles with their label about turning down the Warped Tour, which the band members saw as cheesy but was expected of young, punkish bands trying to make it big. Riddle saw BYOP's penultimate show at the Reading Festival in England, where he says he could just feel the band ripping apart at the seams, a memory that still resonates with him. "It is so stressful, and it freaks you out," he says. "Going from just being a normal kid to being a rock star — and they were — it is a big leap."

Be Your Own Pet may have burned up on re-entry, but everyone has gone on to do interesting things. Guitarist Jonas Stein made Turbo Fruits his main gig, and Riddle eventually signed them to Serpents and Snakes. Stein also started the seafaring indie-rock festival The Bruise Cruise with booking agent Michelle Cable. Jemina Pearl and drummer John Eatherley teamed up for an album on Thurston Moore's Ecstatic Peace imprint, and Pearl now plays in the heavy-blues outfit Ultras S/C. Nathan Vasquez has continued to play with the criminally underappreciated Deluxin' and other projects. Eventually Jamin wound up with a bigger record deal than the one his dad called him crazy for walking away from — though that isn't the reason he left.

In some ways they were just another young band that couldn't keep it together, but they were also much more than that. As Riddle puts it: "You can still track the influence of that group of kids throughout the whole Nashville scene today."

[page]

In 2008, soon after Jake and Jamin put everything they owned in storage and quit their jobs to pursue music full time, the brothers sat down with Bob and told him they would be limiting Infinity Cat releases to young, hard-charging bands like their own. That meant no more albums by Monkey Bowl, Bob's solo project that had caused a minor stir with a song called "Al Gore."

"I got kicked off my own label," Bob says with an amused grin that only a proud parent — and one with a 3-million-seller plaque on his office wall — could conjure.

That same year, Infinity Cat issued another pivotal release: MEEMAW's Glass Elevator EP showcased the feral stylings of Jessica McFarland, the off-kilter, catchy songwriting of Daniel Pujol and the hangdog goofs of former Cowboy Dynamite frontboy Wez Traylor. Like Be Your Own Pet before them, MEEMAW was entirely too good for how young its members were. And though they never shot to the heights BYOP did, they unraveled almost as fast. Bob couldn't believe it when they split up. "You're like The Clash," he remembers telling them. "You're that good — and you haven't even made your Sandinista yet!"

Like BYOP (and unlike The Clash), MEEMAW yielded offshoots that continue as productive touring bands today: McFarland fronts the raved-up punk quartet Heavy Cream; Pujol lends his whip-smart songwriting to the eponymous PUJOL; Traylor cracks wise on bass and vocals with the Stones-y party band Natural Child. Both PUJOL and Natural Child have since moved on, to Omaha's Saddle Creek and Fullerton, Calif.'s Burger Records, respectively.

Lately, Jake has been thinking about how to make Infinity Cat smarter and more efficient.

"We tried to put out too much stuff [last year]," he says wanly. "We could have been a profitable label."

Before he can finish that thought, his phone lights up with a text from Richie Kirkpatrick, aka Ri¢hie, the wily, mustachioed guitarist perhaps best known as the former frontman of Ghostfinger, or as the guy who played the guitar parts on Jessica Lea Mayfield's 2011 album Tell Me that many critics assumed were Dan Auerbach. Jake looks up at his brother inquisitively.

"You wanna do a Ri¢hie 7-inch?" Jamin nods almost imperceptibly.

Jake glances back down at his Blackberry. "I'd love to do a Ri¢hie 7-inch," he says, gritting his teeth. "I love his music. But this is exactly the kind of record I'm trying to stop putting out."

That's because singles are expensive, and Ri¢hie doesn't tour enough to help drive sales. "You can't make money on the first pressing of a 7-inch," Jake explains. "The unit cost alone is $4."

The decision seems to weigh on him a bit, but he's got plenty else to think about. The band's longtime live sound tech won't be joining them on what Jake calls "probably our most important tour," leaving the band's signature massive sound at the mercy of a different front-of-house engineer every night.

The tour is big because Hypnotic Nights is the first album to come out fully under the auspices of the Warner label group — complete this time with an official press release from Warner calling Infinity Cat a "family-owned, super cool, vinyl-centered record label ... which has been a pillar of support for Nashville bands." And all the attendant album promotion includes the Infinity Cat logo, presenting the Orralls with their best chance yet at reaching a much wider audience.

"The logo is a hyperlink!" the elder Orrall interjects from the other room. "It directs people to the website."

"Hyperlink," Jake says with a mocking grin, thrusting his arm as if to send it rushing through an imaginary series of tubes.

"That's part of the idea with the Warner deal," band manager Holland Nix explains, "to bring attention to the label." (Nix also owns a partial stake in Infinity Cat.) Under the agreement, Infinity Cat retains all rights to the band's back catalog, which Jake calls "pure profit." And the partnership with Warner doesn't change the label's basic structure — Infinity Cat remains purely independent.

And if JEFF the Brotherhood really does continue to blow up the way many think they could, they might have to retrofit their pop-and-bros business to run on a larger scale. "I remember really distinctly in 2009 thinking that in a few years this band and their label would probably be much bigger than they were," Pitchfork's Pelly says. She describes a recent JTB performance in Brooklyn as "one of the best shows I have ever been to in my life."

In any event, the impact the label has had on indie rock in Nashville, and its reach around the country and the world, is undeniable — a perspective shared by Metro Councilman At-Large Ronnie Steine, who introduced resolution No. RS2012-339, which proclaims: "It is fitting and proper that the Metropolitan Council recognizes Infinity Cat Recording on its 10th anniversary as one of Nashville's best independent labels." To celebrate, the I-Cat crew is throwing a pair of birthday shows: July 20 at Exit/In — with a reunited Skyblazer featuring Jake, Jamin and Lindsay Powell, aka Cake Bake Betty — and July 21 at The Zombie Shop.

It's nearly impossible to draw the connections between bands and band members in Nashville's indie-punk underground without starting at, passing through, or ending up somewhere on the Infinity Cat family tree. Thinking it would be fun to literally draw those connections, Bob hung a sheet of paper in the hall and asked everyone to help fill it out. Both Jake and Jamin rejected the idea outright.

"We didn't want to do that," Jamin says. "We don't feel like, 'We started all this,' or anything like that." And the brothers don't want to give anyone the impression they think that way. They're quick to credit promoters like Matt Walker and Chris Davis, who booked them early on. But what they did start on their own has proven to be a crucial conduit, if not the only one, for a thriving DIY subculture.

Over the past decade, the label has released some of Nashville's defining indie-rock records, their roster reading like a who's who of the rafter-shredding scene that has thrived in basements, small clubs and makeshift venues while also vaulting onto some of Nashville's most storied stages. (After years of playing parties anywhere that could hold a P.A. and a few dozen people, JEFF the Brotherhood made their debut at The Ryman on Sept. 15, 2011, opening for The Raconteurs.) And while Be Your Own Pet didn't make Infinity Cat a household name, the band did land some of the first punches against that old Music City bugaboo — the notion that Nashville is nothing but cowboy hats and country songs — while also laying the groundwork for an updated image of Nashville as a place fueled by young, hungry bands and suffused with a fiercely independent spirit.

"Who knows where Infinity Cat and the artists on its roster will be in another 10 years," Pelly says, "but regardless, they've done a great job documenting a very specific scene that to my knowledge, wouldn't have been documented otherwise. That kind of work doesn't lose value."

If Jake thinks about things like legacy, he doesn't talk about it. And he laughs when asked about the Infinity Cat logo: "That's just something I used to draw on all my notebooks at school. My teacher said, 'That drawing will make you a million dollars someday,' " he recalls, unable to contain his amusement at the very thought.

But considering their track record, their steadfast adherence to their aesthetic guns and their uncanny instincts, it would be hard to bet against the Orralls. Could JEFF the Brotherhood be what Helmet was to Amphetamine Reptile, or what Nirvana was to Sub Pop, and break the whole thing open for their little homespun record label? Impossible to say. But fans of the label with the quirky, monosyllabic slogan — "come like it now with us" — have come to believe one thing: Whatever the particulars, it's going to be good.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.