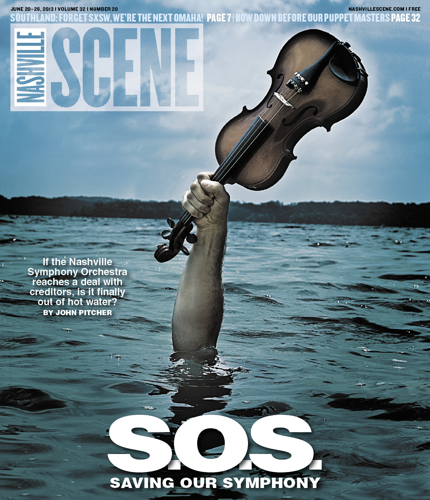

For the Nashville Symphony Orchestra — an ensemble that had previously weathered a recession, financial crises and even the weather itself — the phrase "face the music" has taken on unfortunate new meaning.

Eyebrows raised earlier this year when the NSO board announced that it did not plan to renew a letter of credit totaling some $100 million in outstanding bonds. The bonds had been used to build the symphony's gleaming new concert hall, the Schermerhorn Symphony Center, an edifice built to exacting acoustic specifications to match the orchestra's world-class ambitions. The symphony's finances took a massive hit from the flood of May 2010, four years after its opening.

If not renewing the letter of credit was intended to get the banks' attention, it worked only too well. Earlier this month, after negotiations stalled on repaying the Schermerhorn debt, Bank of America initiated foreclosure proceedings. The bank took the dramatic step of announcing a public auction of Nashville's magnificent symphony center. As of press time Wednesday morning, that auction was still scheduled for 10:30 a.m. June 28, at the main door of the Davidson County Courthouse.

As the Scene was going to press, sources familiar with negotiations between the NSO and the banks indicated that terms of a settlement were being worked out. If indeed the banks agree to retire some of the NSO's debt — a frankly magnanimous gesture that would silence accusations of predatory lending that followed the foreclosure announcement — and if the orchestra makes needed cuts that would improve its fiscal outlook, the NSO may have survived the biggest crisis in its 67-year history.

"Banks and donors are both going to want to see an orchestra put some skin in the game," says David Hyslop, a veteran orchestra administrator currently serving as interim chief executive officer of the Louisville Symphony, which has faced its own share of hardships. "To be taken seriously, you have to show you are willing to compromise and make cuts."

Yet even if an agreement is reached, the orchestra still faces a path strewn with obstacles. No sooner will one round of negotiations end than another will begin — this one with the NSO's own musicians, whose contracts are up July 31. Talks were scheduled to begin Wednesday between orchestra management and the musicians union, Nashville Musicians Association, which made a public statement earlier this month refuting arguments that musician salaries are part of the problem.

Beyond that looms a series of difficult questions about the future of the organization and others like it across the country. In a struggling economy, is a world-class symphony orchestra worth the resources it must have to meet its ambitions? And if it cannot meet those needs with patronage alone, should it be subject to the same economic Darwinism as every other arts organization struggling to pay the bills, and left to fail?

At the moment, however, assuming a settlement holds, the pressing concern is how the orchestra can avoid a repeat of its present predicament, and satisfy its supporters' demand for top-notch performances while eyeing the bottom line. For that reason, it's worth examining how the current situation began.

The extent of the NSO's fiscal trouble only became public in March, when the executive committee of the orchestra's board of directors refused to renew the letter of credit. But a review of the NSO's tax records and audit reports going back eight years reveals that the orchestra's financial difficulties had been going on much longer.

In an interview with the Scene in March, NSO President Alan Valentine noted that some of the initial problems were seen as normal growing pains associated with moving into a new and complex symphony center. "We learned that some things were going to be more expensive than we initially thought," Valentine said. "But we were not in a crisis in the beginning."

The symphony's tax returns bear out that statement. On its 2008 tax form, the orchestra reported income of $51 million and expenses of $38 million. But those healthy figures proved to be deceiving. In early 2008, the orchestra was still living off robust ticket sales, grants and donations from the prior season. Once the effects of the economic meltdown and global recession finally kicked in, the NSO's budget numbers crashed.

The orchestra's 2009 tax returns show income nosedived to $14 million, while expenses decreased only slightly to $33 million. Of course, all nonprofits in America suffered considerably at the time. But the Nashville Symphony's situation was somewhat unique in that its finances were extraordinarily leveraged due to its new concert hall.

It was at that point that the orchestra's letter of credit on the Schermerhorn first came up for renewal. According the NSO's 2009 audit report, completed by the firm Crowe Horwath, the letter of credit issued by Bank of America was renewed on Jan. 9, 2009, for one year "at a significantly higher cost to the [orchestra]," with fees on the letter of credit soaring 235 percent.

After that, the symphony's woes went biblical.

Crowe Horwath's audit of the NSO's 2010-11 fiscal year noted that the Schermerhorn was located "in a 500 to 1,000 year flood zone, and therefore, [was] not particularly susceptible to flooding." The Cumberland did not receive the memo. The May 2010 flood that crested 11 feet above flood stage came as both a surprise and a painful blow to the Nashville Symphony, destroying instruments and submerging its lower floors under 24 feet of brackish river water. Damage to the Schermerhorn was estimated at around $40 million.

"The 2010 flood was incredibly bad luck for the Nashville Symphony," says Drew McManus, a Chicago-based consultant who writes the orchestra business blog Adaptistration. "I am convinced that if it hadn't been for that flood, the Nashville Symphony wouldn't be in its current financial predicament with the banks."

The symphony was able to recoup most, though not all, of its losses with funds from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and from other insurance. But that didn't shield the orchestra from the initial monetary tsunami. "People may think FEMA comes out and writes you a check for $40 million, but that's not the case," Valentine told the Scene in March.

Although the NSO and its music director, Giancarlo Guerrero, continued to win accolades and Grammy Awards for their recordings of contemporary American music, the orchestra never recovered financially. The NSO's most recent audit report, in fact, shows the organization had been out of compliance with its letter of credit for much of the 2012-13 season. The orchestra entered into a forbearance agreement with Bank of America in November 2012 while the parties continued to negotiate the debt.

In March, when the NSO board opted not to renew the letter of credit, it said the action was intended to focus the bank's attention on the need to come to terms. The board got everybody's attention, but it also prompted Crowe Horwath to question the orchestra's ability to remain a "going concern." For those who scoff at the resources it takes to build a great orchestra, their concerns won't end with an agreement that settles the NSO's present dilemma.

[page]

While the NSO's financial crisis has caused a lot of uncertainty and confusion, one thing is guaranteed: Orchestras that have gone through these ordeals in the past have always emerged as leaner, meaner organizations.

Last year, the Detroit Symphony completely resolved a $54 million debt on its Max M. Fisher Music Center. Paul Hogle, the DSO's executive vice president, noted that it took the orchestra at least three or four years to finally hammer out an agreement with its banks, which included Bank of America. And before that agreement could be reached, Detroit made a series of painful cuts that included the elimination of 39 staff positions and a 23 percent reduction in musicians' pay.

"We were able to negotiate successfully with the banks because we proved we were willing to engage in a serious give and take," Hogle says.

Although the DSO's worst days are now behind it, the orchestra did not emerge unscathed. The ensemble experienced a 26-week musicians' strike that was remarkable for its acrimony. A number of the orchestra's top musicians, including its former concertmaster, left for other orchestras or academia. Understandably, the orchestra's brand — the DSO is widely considered to be one of the country's top 10 ensembles — took a beating.

The NSO's current management, in contrast, has up to now had an enviable relationship with its musicians. That relationship will now be put to the test.

"I imagine the NSO will do everything it can to stay on good terms with the musicians," says Hyslop, the Louisville Symphony's interim CEO. "That will make it easier for the organization to move forward in the future."

When the severity of the Nashville Symphony's financial crisis first came to light in March, there was hope the orchestra might avoid the sort of labor strife that has plagued other troubled ensembles.

"The Nashville Symphony musicians support our management team and board of directors and are thankful and grateful for the support from all of our patrons," the Nashville Musicians Association said in a conciliatory statement in the spring. "It is our hope that the current discussion with the banks will ultimately be about the importance of great art and music."

With negotiations looming, though, the musicians have sounded a decidedly more dissonant note. "This financial problem was not caused by the musicians nor is it because the musicians make too much money," the union said in a statement issued earlier this month. "We will not concede to a tug of war between attorneys, bankers and bean counters."

Yet orchestra experts say that’s exactly what the musicians may have to do to resolve the current crisis, which could reach a crescendo next week. For its part, the NSO has already sought cuts elsewhere in hopes of appeasing the banks. On Tuesday, the symphony announced it will discontinue its in-house food service operation at the Schermerhorn effective Aug. 4. NSO spokesman Jonathan Marx wrote Tuesday in an email that the move would affect 16 full-time food service positions, two full-time events employees and 21 part-time on-call staffers, although the symphony will continue to offer food and beverage service through outside vendors.

It's perhaps no coincidence that the announcement of the food service cuts came the day before the musicians were scheduled to start contract negotiations. The move put added pressure on the musicians to be flexible. But it still won't be easy for them to make concessions. The musicians, after all, are the orchestra.

Indeed, the players justifiably take credit for much of the ensemble's recent artistic success under conductor Guerrero. In a statement released Monday, the musicians noted, "During the term of this [six-year] contract the NSO rose into the ranks of America's great orchestras, and the results are tangible: seven Grammy Awards, acclaimed sellout performances at home and at prestigious venues such as Carnegie Hall."

Everything in that statement is unassailably true. Furthermore, the symphony was among 19 orchestras honored this week for bold program selections at the prestigious League of American Orchestras National Conference in St. Louis. The NSO picked up an ASCAP Award for Adventurous Programming, with special recognition for its support of contemporary composers such as Richard Danielpour, John Adams and Edgar Meyer.

Moreover, Nashville Symphony musicians don't have as much to give back as many of their peers in other premium orchestras. Under their current contract, the players earn a base salary of $60,000 for a 44-week season. That's a respectable sum, to be sure. But it doesn't approach the head-spinning six-figure amounts earned by musicians at many other top-flight ensembles.

"Our musicians already receive the lowest salaries in the budget category," NSO President Alan Valentine told the Scene in March. And orchestras, by definition, are difficult to trim because of the nature of the music they play. After all, the Mahler piece the NSO performed last year to large audiences and acclaim is called the Symphony of a Thousand, not the Symphony of a Dozen.

Valentine, who was instrumental in building the NSO's new reputation and standing — and who did not respond to requests for an interview — has expressed a strong distaste for cutting his musicians' compensation. His preferred solution to the current crisis has been to search for new sources of revenue. Toward that end, he has altered the mission of the Schermerhorn from being primarily a classical symphony hall to becoming a performing arts center that routinely books such big-name acts as Bill Cosby and Lyle Lovett.

The changes won't stop there. Starting in the fall, the NSO will cut back on its classical programming, eliminating seven of its Thursday-night classical concerts and replacing them with a shortened "Coffee and Classics" series. The NSO will also put a greater emphasis on its pops programming. "People who go to our pops series are entertainment buyers who are attracted to the hall for different reasons," Valentine told the Scene in March. "We think those concerts can be more profitable."

Unfortunately, Valentine’s grow-our-way-out-of-distress approach has yet to satisfy lenders. In a terse prepared statement to the Scene earlier this week, before word of a potential settlement, Bank of America spokeswoman Shirley Norton noted that the NSO “is in default and has been unwilling or unable to repay the debt. Left with no other alternative the bank group has been forced to file for foreclosure, always a last resort.”

But if an alternative has indeed been found, the orchestra's challenges in a sense are just beginning.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.