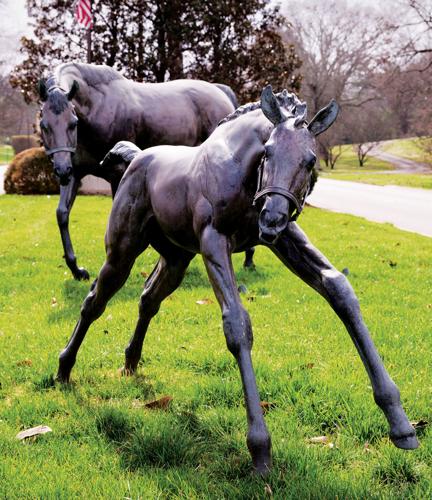

Belle Meade Plaza sits just outside the Belle Meade city limits. A few hundred yards away, two metal horses mark the beginning of Belle Meade Boulevard, which branches off Harding Pike near Belle Meade City Hall and runs nearly four miles to the base of the stone steps at Percy Warner Park. Like the horses, the Allée Steps are a city symbol, a celebration of its beloved backyard.

Belle Meade’s charter bans commercial activity inside city limits, part of a list of land use prohibitions that includes duplexes, open carports, rental properties, trucks and billboards. Aside from five exceptions — three churches, William Giles Harding’s plantation home (now a tourist attraction and winery) and the country club — Belle Meade’s three square miles consist of single-family residences.

The Kroger at Belle Meade Plaza is the closest grocery store. There are a few storefronts down the strip, and Starbucks is a preferred coffee shop, passively competing with a new Dunkin’ and an old Bruegger’s Bagel Bakery farther down Harding. While local chains like Crema, Barista Parlor and Frothy Monkey expand across Nashville, the Seattle-based international chain earned local loyalty.

Belle Meade Boulevard

Real estate developers AJ Capital, based in Wedgewood-Houston, have slated the entire Belle Meade Plaza strip for an overhaul. The project faces staunch opposition by residents who have already scored reductions in building height and living units, a mixture of condos, apartments and hotel rooms. Concessions have followed months of tense meetings between architects, planners, traffic engineers, District 24 Councilmember Kathleen Murphy and the opposition, an increasingly organized group of residents who speak out of turn and keep the gallery loud.

“Don’t ‘Gulch’ my West Nashville,” said one opponent at a community meeting at Montgomery Bell Academy in January. AJ Capital plans to change the site’s uses from purely commercial to a mix of residential and retail, and needs Murphy’s support for a zoning change to allow a complete redevelopment of the corner parcel at White Bridge Road and Harding — a busy intersection that, residents fear, can’t take more traffic.

“The noise, process and duration of demolition and excavation is bone-rattling,” says another resident, providing a blanket criticism of large-scale construction. The opposition comes from surrounding neighborhoods like West Meade, Forest Hills, Sylvan Park and Belle Meade. Speakers insist they aren’t against change in general; they oppose this project’s specifics. In rowdy Q&As, they skewer AJ’s proposal as reckless density motivated by greed, alternatively calling for fewer units and units below market rate. (Per state law, it is illegal to force developers to include affordable housing in new builds.) At any mention of a traffic study, they attempt to discredit engineers’ methodology. The same West End corridor — Belle Meade specifically — helped kill Let’s Move Nashville in 2018. The $5.4 billion transit plan would have put a dedicated transit line down West End ending at the same plaza Kroger, depriving drivers of a critical turn lane on West Nashville’s major arterial. Back then, opponents said the same thing: It’s the specifics, not the idea.

No neighborhood is positioned to stop change quite like Belle Meade. It is perhaps Nashville’s most affluent three square miles, and residents have the time to engage in their surroundings. There’s a common if abstract understanding of Belle Meade’s character built on wide green pastures, old-growth trees and tasteful, classical architecture, all on the shared grounds of a historic plantation estate where the world’s finest thoroughbreds once grazed. The city has complete authority over zoning and building codes, allowing planners and residents to work hard to insulate the area from Nashville’s explosive growth. Belle Meade is armed with a new historic zoning commission that can impose additional restrictions on building, reinforcing a sense of control for longtime residents witnessing change across the city. Even though the plaza lies just outside Belle Meade city limits, locals come to outgoing city manager Beth Reardon hoping to stop it.

“With the change in Nashville, its growth so sudden, we got a lot of influx of developers buying houses, demo-ing properties, and putting up houses as quickly as they could,” says Reardon, who’s ending a 32-year career at Belle Meade City Hall. “You’re not going to find tall-and-skinnies in Belle Meade. Our subdivision regulations are not going to allow that.”

Nowadays it’s nearly impossible to increase the city’s density. Andrew Pieri, Belle Meade’s building codes consultant, calls it “conceivable” but mired in variables. Even if homeowners had a lot big enough (the city has a minimum lot size of 1 acre), they’d face all kinds of restrictions on road frontage, driveways and setbacks. When asked about subdividing a lot, Reardon shakes her head and laughs.

“Even though it’s in the middle of this metropolitan, urban, fast-growing city, Belle Meade has been insulated from that change,” Jennifer Moody, Belle Meade’s incoming city manager, tells the Scene. Moody’s first day as city manager was Feb. 27. Reardon’s still helping with the transition and expects to be gone by April 1. “That special sense of place — that small-town feel — is at the heart of what we’re trying to preserve. Residents have local control. They have an elected body governing them of residents who live right here. It adds to a sense of feeling represented, of being able to protect your interests.”

Belle Meade Plaza

Davidson County voters passed a referendum to combine city and county governments in 1962. Belle Meade, along with five other “satellite cities,” didn’t join. A sixth, Lakewood, merged in 2011. Some municipal services, like trash and zoning control, stop at the city limits. Metro provides others, like the fire department.

In the years that followed consolidation, many of Nashville’s wealthy white families withdrew from the city center, moving to enclaves like Belle Meade as well as Oak Hill and Forest Hills, both of which also retained city charters through consolidation. Belle Meade kept control over a small police force, a part-time judge with a part-time courtroom, and land use. For 60 years, the area has stayed committed to a distinct array of social institutions, cultural landmarks, outdoor recreational opportunities and a network of exceptional private schools. Meanwhile, Nashville has changed around it.

Residents’ desire to preserve Belle Meade’s look, feel and character can be so fierce that, at times, it even baffles city administrators. Twenty years ago, residents killed a sidewalk master plan meant to make the boulevard more pedestrian-friendly. A scaled-down version that would have put walking paths in the boulevard’s median died a quiet death last year after widespread pushback.

“We had a landscape architect design a great plan for the city,” Reardon explains to the Scene. “It was shot down by residents who said, ‘We don’t want sidewalks here, you’ll change the whole look of the boulevard. This is going to destroy everything we have now. We don’t want people walking all over the place.’ Last year we put in a temporary gravel path in the median as a demonstration project. Again people said, ‘Absolutely not, you’re destroying the look of our beautiful median.’ There was a huge level of engagement — 750 comments in a town of about 3,000.”

Steve Roche moved to Belle Meade in the winter of 1998 to be closer to Harding Academy, where he planned to send his children. At a meeting about last year’s proposed sidewalk demonstration, Roche remembers one resident voicing concerns that people would start parking along the boulevard and hosting barbecues on the median.

“I had to ask her to repeat it — I thought she was joking,” Roche tells the Scene. “It was a fine plan. I thought it was great. A lot of people were complaining, and all the people who were upset made their case known. That’s what’s sad — I think those people are a fifth or a seventh of the population. The people who wouldn’t mind it, they don’t ever come out.”

A rash of construction in the 2010s prompted tighter restrictions on what can (and can’t) be built in Belle Meade. In summer 2019, the city engaged the Tennessee Historical Commission to produce a “Historic Resources Survey,” which proposed three special districts — East, West and South — and a district that would blanket the entire city. These maps codified Belle Meade’s architectural character, structuring what would become the city’s Historic Zoning Commission a few months later. Such districts come with additional building specifications, exterior guidelines and an approval process in which the historic commission makes construction permits contingent on aesthetic and architectural guidelines. Metro Nashville has a similar process in neighborhoods like Richland, Germantown, Hillsboro-West End and Edgefield.

Residents complained that too many new houses didn’t fit the Belle Meade character and disrupted the feel of the neighborhood, citing details like brick color, materials and architectural cohesiveness. Officials responded. At the time, then-director of Belle Meade building and zoning Lyle Patterson told media that the city was responding to demo permits and homes built “on spec” — construction done by a developer rather than a future resident.

The new HZC now issues a “Certificate of Appropriateness” allowing builders to move forward with their designs. The application asks for details like chimney material and gutter dimensions, all keeping with the commission’s explicit purpose to “encourage development that is compatible with the city’s historic character.”

Belle Meade Historic Site and Winery

For a century, Belle Meade had one official residence: a grand plantation home established by John Harding of Virginia in 1807. The estate passed to his son William Giles Harding in 1839, growing in size, wealth and prestige as Nashville flourished in the antebellum years. Forced labor staffed the house and grounds, which swelled from the 250-acre tract purchased by John Harding to 5,400 acres under William Giles. By the eve of the Civil War, 136 Black residents were enslaved across the estate, including 63 children younger than 10, according to census records.

Historian Brigette Janea Jones has helped bring a fuller picture of the estate’s history to the Belle Meade Historic Site and Winery, Harding’s original plantation home currently serving as a tourist attraction with guided history tours (and wine). Jones started at Belle Meade in 2015 and became its first director of African American Studies in 2018. Her work has brought a renewed focus on the complex, often forgotten lives of Black residents enslaved at Belle Meade, including their histories of escape and resistance.

William Giles Harding was a brigadier general in the Tennessee State Militia and used his wealth to finance the Confederate rebellion. When the Union took Nashville early in 1862, Harding was sent to Fort Mackinac, a Union prison in Michigan. After swearing allegiance to the Union, he returned to the South. Harding maintained ownership of Belle Meade after the war and welcomed the 1866 marriage of his daughter Selene Harding and William Hicks Jackson, a fellow high-ranking Confederate brigadier general. Jackson took control of the land in 1883, by which point Belle Meade had gained an international reputation for its horses. Shortly before his death in 1902, Jackson, saddled with debt, started selling off the estate.

Private residences began popping up across Belle Meade a few years later. Hastened by a new streetcar line laid out down Belle Meade Boulevard in 1913 and Belle Meade Country Club’s relocation in 1916, mansions gradually replaced meadowland. The area went from 22 buildings in 1920 to almost 400 by 1940 — the area’s first building boom.

The ethics of preservation, conservation and neighborhood character have long defined Belle Meade politics. Moody mentions a tale about how the city incorporated in order to keep a gas station from moving onto the boulevard. Reardon recalls the election of former Mayor Elizabeth Proctor, who — in the early 1980s — won her seat by successfully harnessing residents’ frustrations with homes built in a cul-de-sac on Bonaventure Place. Current Mayor Rusty Moore tells constituents that he is “committed to preserving the uniqueness of our community, maintaining our property values, and helping keep our neighborhood safe for future generations” in a brief city bio.

In exchange for an extra property tax levied on residents, the city promises a few special services. One lifelong resident describes these to the Scene as “perks,” slight upgrades on the Metro treatment enjoyed by the rest of the city. About half the Belle Meade city budget goes to a local police force staffed by eight officers, four sergeants, a lieutenant and a police chief. Tasked with covering just three square miles, Belle Meade cops are notorious for catching speeding drivers often unaware that they’ve entered a tightly monitored satellite city. Residents praise BMPD for quick response times and keeping a vigilant watch over the city, aided by automated license plate readers since 2017. Belle Meade clears brush, maintains green space, manages water and sewer lines, and collects “backdoor” trash pickup — Belle Meade residents don’t have to roll garbage bins out to the street. While Metro officially runs Percy Warner and Edwin Warner parks, local fundraising helps bypass city bureaucracy to secure improvements and maintenance. In 2021, Friends of Warner Parks, a nonprofit set up to improve and maintain the 3,100-acre woods, completed a $15 million capital campaign to fully repair and relandscape the Allée Steps. A similar effort helped secure $2 million for a course redesign at the Percy Warner Golf Course.

A network of elite private schools substitutes for a public education system. In the 1970s, “segregation academies” popped up to absorb demand from white families fleeing integrated public schools. Still predominantly white, many of these schools — Franklin Road Academy, Harding Academy, Brentwood Academy — are fixtures in and around Belle Meade, Green Hills, Forest Hills and Oak Hill.

The ZIP codes that span the same wealthy suburbs, 37205 and 37215, account for 7 percent of Nashville’s population and 2 percent of students enrolled in MNPS schools. Today just 70 students within the Belle Meade city limits are enrolled in Metro Nashville’s public schools, according to MNPS. Neighbors favor private schools like Ensworth, Montgomery Bell Academy, Harpeth Hall and University School of Nashville, where yearly tuition sits at or above $25,000. They’re also conveniently located, reflecting a historic tie between Nashville’s prestigious prep schools and the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods. Harding and Harpeth Hall are almost inside Belle Meade proper. MBA is just down the road. Christ Presbyterian Academy and Brentwood Academy are 10-minute drives out of town, as is Ensworth High School. Such education preferences were on display in Belle Meade in the spring and summer of 2020, the era of yard-sign graduation announcements.

Census data puts the city’s annual median income at $208,304 — more than three times the Davidson County average. Residents skew older and 94 percent are white. Just seven homes are on the market as of this writing, including a 16,000-square-foot chateau on Westview listed for $15 million. An English tudor across the street is listed for $4.2 million. City policies also safeguard an unofficial city service that Mayor Rusty Moore makes explicit. Like Jackson and Harding before them, Belle Meade residents store tremendous wealth under their feet.

Belle Meade Country Club

Belle Meade is home to the Frists and the Ingrams, Nashville’s highest-profile billionaire families. They’re neighbors on Chickering, keeping stately residences near Percy Warner Park. Ingram Industries set up headquarters just down the street, and HCA Healthcare was incubated by the Frists in and around the power centers of the big small town in the late 1960s. Down the road lives Republican junior U.S. Sen. Bill Hagerty. Writer Jon Meacham, celebrated for his commitment to chronicling the nation’s history, lives in a Georgian mansion on 4 acres between Tyne and Chickering. Al Gore keeps a home on Lynnwood, and former state House Speaker Beth Harwell lives across the boulevard facing the fairways of Belle Meade Country Club.

“The Club,” as it is known, sits at the physical center of the city. It’s a hub of social life and Belle Meade’s only commercial dining option, featuring an upscale dining room, a robust takeout operation and a kid-friendly summer snack bar. A full guide to etiquette at the club’s seven restaurants can be found online. The club’s one-time initiation fee hovers around $150,000 and requires sponsorship from current members, all part of an admissions process shrouded in secrecy. There were a little more than 1,200 memberships on file as of last year, spread over several categories: resident, non-resident, associate (ages 30 to 34), associate (ages 35 to 39), associate resident, senior resident and lady — the latter a distinction for unmarried women.

An internal directory obtained by the Scene does not include demographic data, but the club has long been scrutinized for having few non-white members. In 2008, the Scene wrote about David Ewing’s long wait for acceptance into the club. In 2011, a judicial ethics panel reprimanded Judge George Paine, then chief justice of the Bankruptcy Court of Middle Tennessee, for membership in an organization that practices “invidious discrimination.” Paine retired later that year. Recently, club decision-makers reckoned with a prominently displayed portrait of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. After surviving a couple relocations, the painting was taken down.

“There is no portrait of Robert E. Lee currently hanging in this building,” a club manager told the Scene in early March. As for the portrait’s recent whereabouts? “I cannot speak to that.”

A commitment to tradition in Belle Meade has coincided with reactionary politics. Trump won the city in 2016, though he was Republican primary voters’ second choice behind Marco Rubio. Trump won the city again in 2020, just barely, while Joe Biden won Davidson County 2 to 1. Hagerty won his neighborhood handily in 2020.

As development creeps closer, residents are anxious, and conservative, about the future. At a packed Feb. 15 community meeting, attendees asked about the office park across the street from Belle Meade Plaza. Neighbors had gotten used to Ingram’s 11-story office building, which went up in 1985. Metro’s zoning department respected Ingram as a height precedent for the area, and AJ Capital planned to match it. What would stop the same thing from happening up and down Harding?

“Fortunately for me, I’m out of office in August, so that won’t be coming up in my term,” Kathleen Murphy told the room. “I can’t predict what will come there, and neither can the planning department.”

Through a decade of tall-and-skinnies, urban infill, boutique hotels and trendy coffee shops, the city of Belle Meade and its skirt of commercial strips have survived mostly untouched. While the rest of the city struggles to pay rent or beat out all-cash offers, large wooded lots from Oak Hill to West Meade steadily gain value, boosted by a market too short on supply. While the rest of the city struggles to book a table at the latest James Beard nominee, Belle Meade has Sperry’s, a wood-paneled steakhouse on Harding Pike preparing to enter its 50th year. While trends in city planning begin to prize walkability and density over cars and single-family estates, Belle Meade hopes to preserve its own way of life.

After three decades with the city, Reardon sums it up.

“We are what we are, and what we have been, since we were incorporated in 1938.”

The Allée Steps at Percy Warner Park