Ellen Lehman of The Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee

The water was still rising in Houston earlier this year when the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee announced it had set up a Hurricane Harvey Recovery Fund. The massive hurricane crashed ashore on Aug. 25, dumping more than 40 inches of rain on southeast Texas and killing at least 82 people in the state, on its way to becoming one of the costliest natural disasters in American history.

Amid the chaos and devastation, the fund served as a trustworthy portal through which locals dismayed by the suffering they saw on television — and unsure of where to contribute financially — could give money to nonprofit organizations working on the ground in Houston. Not a single cent was held back for overhead or someone’s salary. All of it went to Texas.

A little more than a month later, the foundation marshaled its resources in the direction of a man-made disaster — the mass shooting at the Route 91 Harvest country music festival in Las Vegas that left 58 people dead and nearly 550 people injured.

The foundation, started in 1991, has been “connecting generosity with need” in response to disasters since an ice storm crippled Nashville in 1993, leaving many people without power and in need of shelter. The organization’s ability to respond to catastrophes far and wide, funneling financial gifts directly to local organizations in the affected areas, has been honed over the years — through responses to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Nashville flood in 2010 and last year’s deadly fires in Gatlinburg. That sort of rapid charitable response might be the reason you know the foundation exists. But it represents just a small piece of the foundation’s overall mission.

For more than 25 years, the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee has been like a loving parent to Nashville’s nonprofit sector. It provides training and services to nonprofit organizations, both fledgling and established ones, and has led an effort to eliminate redundancies and increase efficiency in the nonprofit community, by offering, for example, the kind of back-end services that could drain a small charitable organization of time and money. The foundation is now home to hundreds of individual funds, each with its own specific purpose, from which money is directed to myriad charitable causes.

“Think about the Community Foundation as a gigantic wall of charitable cubbyholes,” says Ellen Lehman, the foundation’s founder and president. “We’re the outside edge and the back. We provide the systems and the structure and the stability, and we provide the stewardship. But each one of those funds can have its own name, can have its own charitable purpose, can have its own story.”

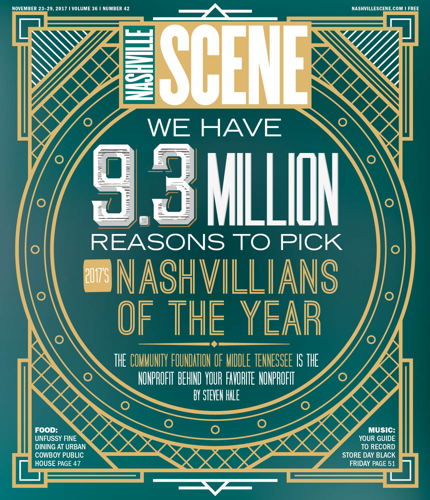

In 2014, the foundation launched The Big Payback, an annual 24-hour charity-palooza that takes Middle Tennessee’s charitable impulse and aims it at a sprawling list of local nonprofits. More than 781 nonprofit organizations participated in this year’s event on May 3, which raised nearly $2.6 million. In four days of giving since its inception, The Big Payback has raised $9.3 million for local nonprofits supporting everything from retired elephants to teenage mothers.

For all these reasons — for working to improve the health of Nashville’s nonprofit sector and empower the generosity of Middle Tennesseans — the people behind the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee are our Nashvillians of the Year.

Lehman does not skip a beat when asked how she got into this line of work.

“Fools rush in where angels dare not tread,” she says. “That’s it.”

She’s not thrilled about being photographed and seems reluctant to be the subject of an interview, but sitting at the foundation’s office in Green Hills, Lehman is eager to talk about the job she’s had for 26 years now — at an organization that started in her garage.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, she says, there was talk in nonprofit circles about why Nashville was one of the few remaining cities of its size or bigger not to have a community foundation. The model was born in Cleveland in 1914 when Frederick Goff, a prominent banker and lawyer, brought to fruition his vision for an organization that would pool the resources of the city’s philanthropists so they could be used to contribute to charitable work in the city for the foreseeable future. (More than 100 years later, The Cleveland Foundation is still doing just that.)

Lehman was at lunch with Ida F. Cooney — the first executive director of the HCA Foundation, which would later become the Frist Foundation — airing, Lehman says, her frustrations with some of the ways the city’s nonprofit sector operated. Cooney told her she needed to start a community foundation, and soon gave her a stack of books on the subject.

At this point in our conversation, Lehman points to a bookshelf in the conference room, noting that all the books Cooney had told her to read are represented there.

“I came back to her a week later, and I said, ‘Do you have any more books?’ ”

Soon, what was then called the Nashville Area Community Foundation was born.

“This is exactly what we needed,” Lehman says. “We had United Way, which is sort of the charitable checking account of a community, where the money comes in and the money goes out. What we didn’t have was a charitable savings account for the community. That’s what the Community Foundation really is, in essence. It is a place where money comes, it is invested, it is stewarded, and it goes out to do the things that the donors wanted to have done.”

All these years later, the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee serves 40 counties in Middle Tennessee and three in Southern Kentucky. The hundreds of individual funds it now hosts — think of Lehman’s wall of cubbyholes — illustrate the breadth of charitable work that can be supported through this kind of model.

Want to give money to support children with incarcerated parents? There’s a fund for that. Want to contribute to the maintenance of the historic Nashville City Cemetery? There’s a fund for that, too. Contributions to these funds build their endowments, which support the funds’ specific causes.

Recently, the foundation announced that a total of just more than $2 million in grants had been awarded to 346 nonprofit organizations in Middle Tennessee, more than 100 of which are working in Nashville. Local grant recipients include: Thistle Farms, to further its work with incarcerated women; Oasis Center, to provide counseling and advocacy for LGBTQ youth; Musicians on Call, to facilitate live bedside music performances for veterans being treated in local hospitals; and Chick History, to digitize original photographs and letters related to the political activity of African-American women in Middle Tennessee prior to 1930.

The wall-of-cubbyholes model also allows the foundation to further one of its broader goals — making charitable work more efficient in Middle Tennessee. Lehman cites the Crittenton Fund, established in 2001, as a particular example. After nearly 130 years of providing support for teenage mothers, the directors of the Florence Crittenton Home for Unwed Mothers looked around and realized that many other organizations were doing the same work. So they made the decision to find organizations to adopt their existing programs, and close their doors. What they did next is a big part of what makes the Community Foundation special: They established the Crittenton Fund, which has been awarding grants to organizations and programs working with pregnant, parenting and at-risk youth for more than 15 years.

Less money spent on overhead and duplicative efforts, and more resources aimed directly at their particular mission. And it’s made possible by the Community Foundation.

The Big Payback training sessions, Feb. 16 at the Nashville Airport Marriott

The Big Payback, an online giving marathon, has become one of the foundation’s marquee events, and it’s so impressive because it’s so simple. It’s one day when as many nonprofit organizations as choose to participate are gathered in one digital place, allowing Nashvillians to go on a charitable giving spree. It’s also a good bit of fun, with a leaderboard showing live results throughout the 24-hour period.

As is the case with the foundation’s collection of funds, The Big Payback takes the guesswork out of giving for charitably inclined people in Middle Tennessee. Transparency is essential, so every participating organization is required to have an up-to-date profile on GivingMatters.com, a database created by the foundation that features more than 1,600 nonprofit organizations and includes information about their financials and governance.

It’s been a big success, due in no small part to the Community Foundation team’s dedication — and its ability to overcome technical difficulties.

In 2015, Lehman recalls, with about two hours left in the 24-hour event, the power went out at the foundation’s Green Hills offices. She called home and got the answering machine, indicating her house still had power. So she and the team, which had been huddled at the foundation’s offices, gathered their laptops and moved the operation to her home.

“There were a lot of empty wine bottles at the end of that experience,” she says. “And then we broke the internet the next year.”

No, really. In 2016, the event’s website was hosted by a company called Kimbia, which was hosting sites for 54 online giving events on the same day across the nation. The traffic was too much. Donation boxes on The Big Payback’s site stopped functioning, and eventually the decision was made to end the event four hours early. Despite the speedbumps, the event brought in $2.6 million.

This year’s event was a big success, free of melting servers or other crises. On May 3, a record 781 nonprofits participated in The Big Payback, which once again raised $2.6 million. Donations ranged from $10 to $15,500, with the average gift coming in at $104.59. And again, the results showed the diversity of charitable endeavours the Community Foundation’s efforts support. Animal welfare organizations finished at the top of the leaderboard, with The Elephant Sanctuary in Hohenwald ($125,913 raised) in first place, and the Old Friends Senior Dog Sanctuary ($76,250 raised) in second. Other organizations in the top 10 included Second Harvest Food Bank of Middle Tennessee, Planned Parenthood of Middle and East Tennessee, Alive Hospice and Nashville Children’s Theater.

The Big Payback training sessions, Feb. 16 at the Nashville Airport Marriott

But a deeper dive into the data reveals another sign that the foundation could indeed have the lasting impact that its team hopes for. Of the donors who made financial gifts during 2017’s Big Payback, 6,606 said they were giving to a particular organization for the first time. Since 2014, more than 18,000 people have said that they made a first-time gift during the event.

“Nobody ever makes their last gift to us,” Lehman says. “But people do sometimes make their first gift.”

Through The Big Payback, the Community Foundation is dealing a gateway drug to charitable giving — introducing charitably inclined citizens to nonprofit organizations that need their support. It can be life-changing for the donors, and transformational for the organizations. Some local nonprofits bring in a significant chunk of their annual revenue during that one 24-hour period, but the foundation’s goal is to boost the organizations while teaching them how to be sustainable for the long haul.

“All too often, people think that The Big Payback is all about a 24-hour online giving event to pay back Middle Tennessee nonprofits which have decided to participate,” says Kelly Walberg, a communications manager with the foundation who works on The Big Payback. “And it is. In preparation for The Big Payback of 2018 and during the years that have preceded it, thanks to our generous sponsors, Middle Tennessee’s nonprofits are now conversant in engaging donors through social media, using digital tools they formerly feared — or at least about which they were skeptical.”

The tools and skills that nonprofit organizations acquire through participation in The Big Payback can put them in a more stable position long term, and also expand the kind of work they are able to do.

Take Operation Stand Down Tennessee, which serves veterans and their families in a variety of ways, from housing to career services. Lori Ogden, a certified fundraising executive who joined Operation Stand Down Tennessee almost five years ago, tells the Scene that training and support from the Community Foundation — through The Big Payback — helped the organization diversify its sources of funding.

Operation Stand Down Tennessee had been about 90 percent funded by federal grants, she says. That’s an unstable position for a nonprofit, and one of her first goals was to change it.

“If you’re reliant on one revenue stream, like the federal government — well, every four years the president changes, and so initiatives within the federal government change,” she says. “So you can see where funding can just go away.”

The organization started participating in The Big Payback when it launched in 2014 and brought in $1,955 from 38 individual gifts. The next year, with more training from the Community Foundation, the team brought in $4,315 — a 121 percent increase. In year three, following the foundation’s recommendation to also seek matching funds (gifts from donors agreeing to double the funds raised up to a certain point), it made a massive jump, bringing in $19,195.64 — a 345 percent increase.

This year’s Big Payback was no different. Operation Stand Down Tennessee secured more matching funds and brought in more money — $36,297, an 89 percent increase over 2016. The organization also won $5,000 from the Community Foundation this year for being the most improved organization, an award it success inspired.

“If you go to their training, and you follow what they tell you to do, you can really bring in some great individual gifts,” Ogden says. “They provided great training, we followed their advice, and it worked.”

But bringing in more money through collaboration with the Community Foundation didn’t just help Operation Stand Down Tennessee’s coffers and support its existing work. By diversifying their sources of funding, the organization was able to expand the work it does. Federal funds are reactive, Ogden says. They allow the agency to serve veterans who are already homeless, for instance. But with new money from private sources, Operation Stand Down Tennessee has been able to beef up its efforts to prevent veterans from becoming homeless in the first place.

The work of the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee could easily go unseen — it is the nonprofit behind the nonprofits.

“The thing that has kept me in the same job for 26 years is that I don’t go to people generally and say, ‘You have money, I have a vision, I want your money to accomplish my vision,’ ” Lehman says. “What I always say to people is, ‘What do you want to do, and how can we help you do it?’ ”

Those efforts go on year-round, and the mission is manifest in various ways. Meanwhile, The Big Payback’s site features a large live countdown until the next 24-hour giving marathon.

As of this writing, the clock is at 167 days, 15 hours and counting.