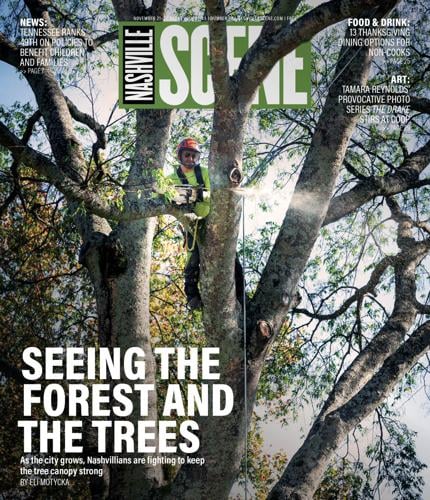

Tree people talk about the canopy like an existential struggle.

On one side, the irreplaceable nourishment of water, sunlight, open green space and air — all fundamentals. Troops, each a sort of caretaker, fan out across Davidson County on workdays and weekends. Caring about Nashville trees means the dual priorities of planting and maintenance. Mature, mighty maples and oaks have survived decades and must be protected from premature death. Nonprofits, the city and private homeowners are planting thousands of young saplings each year, particularly eyeing urban buffer zones dominated by concrete and pavement. Methodical arborists determine how to trim branches in a way that preserves a tree’s strength, or make the weighty decision to facilitate a tree’s death. The city has slowly begun building protections around its canopy, increasingly seen as among the city’s most valuable utilities.

Benefits flow generously from healthy trees. Wood stores carbon — which accounts for about half a tree’s dry weight — efficiently and cheaply. Leafy canopies filter air and function as carbon sinks, drawing down greenhouse gases spewed into the atmosphere. Mature trees increase property values and anchor the local ecosystem. Birds, caterpillars and squirrels share branches. Mighty oaks are places to rest. Climbers reach for low-slung magnolias. Some bear flowers and fruit.

Re-wooding cities with shady trees and green space helps battle what’s known as the urban heat island effect, the public health phenomenon describing how city dwellers suffer higher temperatures living amid concrete, glass and asphalt. Clinical data has shown trees’ capacity to relieve stress and lower blood pressure. Nashville physician and former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, newly convinced of trees’ measurable impact on physical health, compared them to medicine in Forbes a few weeks ago. From 2003 to 2007, as the nation’s most powerful senator, Frist fought environmental protections and supported extractive oil and gas interests. In 2022, he became global chair of the Nature Conservancy. In May 2023, he testified in front of the Senate Budget Committee about the devastating effects of a rapidly warming planet.

Like so much in Nashville, the tree canopy — and its benefits to health, wealth and happiness — is distributed unequally, a bottom-line conclusion of Metro’s 2023 “Urban Tree Canopy Assessment.” Downtown is unsurprisingly naked, with just 8 percent of its 1,667 acres boasting tree canopy. North Nashville and South Nashville, lower-income areas and centers of the city’s Black and Hispanic communities, slot in next with 21 percent and 27 percent UTC, respectively. The city’s overall average tree canopy — respectable 56 percent coverage — is inflated by a heavily wooded rural western edge spanning Joelton to Bellevue. While the canopy has technically grown 1.7 percent since 2010, the places where people live — East Nashville, Green Hills, North Nashville, Antioch, West Nashville — have stagnated or taken 1 to 2 percent canopy losses. In other words, Nashville’s forests are thriving away from its population growth. Lots of people and lots of trees are not mixing well.

On the other side, three primary factors threaten Nashville’s trees, all of which have gained strength in the past decade. Tree destruction has a small green champion: the tiny emerald ash borer, which came to Tennessee in 2010 from Asia by way of Detroit, assumed to have hitched a ride in packing crates. Signage at Percy Warner Park displays its image like a mugshot. North American arborists have completely submitted to the beetle. Insecticide treatment is expensive, ineffective shortly after infection and can destroy the surrounding ecosystem. Professional advice focuses not on saving trees but properly caring for an ash upon infection — the resigned response to a mass killing event.

“The Emerald Ash Borer is attacking all species of North American ash trees and will kill them all unless treated,” reads advice from the city. “No ash tree is immune to the devastating effects of this insect which has been in Davidson County since 2014 and Tennessee since 2010.”

Violent storms tore through the wooded South well before Fort Nashborough — built from milled logs — established white settlers’ expansionist footprint near the Cumberland River. But as the effects of climate change destabilize weather patterns, atmospheric scientists have observed certain increases in the frequency and intensity of tornadoes — the second threat to Nashville’s canopy. Data shows an eastward migration of “Tornado Alley,” putting Nashville in the highest-density patch of multi-twister events.

Each storm tests trees for strength. Brittle branches snap easily; high winds pull weak trees from the ground. Living, flexible fibers survive duress better than desiccated branches, helping strong, healthy trees withstand storm conditions. During heavy rain, a robust leafy overstory mitigates flooding by pacing the flow of stormwater. Still, direct hits can clear-cut a neighborhood or hillside in minutes, throwing mature trees into homes, schools, roads and cars. Twisters uprooted canopies across Madison and Hendersonville in December 2023, and tore over North and East Nashville in March 2020.

Often from fear, ignorance or negligence, the trees’ third enemy — humans — destroys the canopy. Some decisions happen quickly. Homeowners, stoked by cautious neighbors or jarred by storm damage nearby, begin to see the trees in their yard as dangerous liabilities.

“They’re just majestic, non-heart-beating creatures, and they’re typically not hurting anyone,“ says Mike York, the arborist owner of TreeSavvy Nashville. On the day he speaks with the Scene, he’s on site just across the Williamson County line taking down a damaged hackberry in a residential front yard. “I just try to think about if it was my tree. I talk myself out of business all the time — people are afraid of their trees and tell us, ‘Just take it down.’ And I have to say, ‘That’s not what you want to do.’ Especially with the construction boom going on. There are usually other options.”

The industry is full of bad advice and unnecessarily aggressive recommendations, York explains. Tree work can be extremely expensive, and certain methods — particularly the practice of abruptly trimming major branches into stumps, known as “topping” — sacrifice tree health and stability for short-term convenience.

Tree topping in East Nashville

A lucrative real estate bonanza, followed by disruptive development across the county, arrived around the same time as the emerald ash borer. In the context of profit-seeking construction plans, mature trees on a wooded lot can quickly turn into obstacles. Satellite imagery from 2010 shows a densely wooded tract between I-24 and Cane Ridge Road that is now home to the Nashville SC training center, Century Farms Apartments and Tanger Outlets.

“There has always been a tension between the most efficient building processes, which helps with affordability of rent and housing we need, and preserving the natural environment around us,” says Burkley Allen, one of Metro Nashville’s five at-large councilmembers. “I get so many calls from constituents saying developers just cut down every single tree on a property. It’s painful to watch.”

Land use is one of a few areas over which the Metro Council wields direct power. Allen — along with former Councilmember Kathleen Murphy and current Vice Mayor Angie Henderson, a former district councilmember — has helped lead the chamber’s efforts to build a layer of legal protection over Nashville’s canopy.

Starting in the late 2010s, Allen was involved in several pieces of legislation that make up local tree law. BL2022-1121 and BL2022-1122, passed in May 2022, laid out a basic bill of tree rights. Metro law now includes requirements for new trees to replace those that are uprooted, a complicated schedule converting trees to tree “units” and a tree density requirement of 22 units per acre. The city now keeps lists of recommended trees (more than 100, including oaks, elms and maples) and prohibited trees. The entire ash species has made the prohibited list, as have several types of invasive, fast-growing trees that choke the natural canopy. Many, like the purple-pink mimosa tree and the ailanthus, also known as the tree of heaven, currently thrive around Davidson County. The bills also created a new category with even tighter protections: the “Heritage Tree.” Once specific mature tree varieties reach a certain diameter, they may qualify as a Heritage Tree, adding more “unit” value, a stronger protection against their disposal.

Allen is currently drafting new legislation aimed at minimizing incidental but preventable tree damage on active construction sites. As new problems arise in the city, she says, pressure builds on the government to respond.

“Eventually, a certain amount of time passes, and we decide that what we have in place is good, but not enough to preserve existing trees,” Allen tells the Scene. “When we cross the line from incentivizing to punitive measures, that’s where we see tension with builders. Right now, the focus is on strengthening incentives to save existing trees.”

Tree removal permits — required when large-scale developments, including commercial and commercial-residential, clash with mature trees — provide some picture into recent deforestation. Tree removal permits are not required for single-family homes. Since 2020, Metro data shows permits concentrated along major roadway arteries like Dickerson Pike and Gallatin Avenue and inside the I-440 loop. Map the permits and certain hot spots emerge, like the densely wooded plots along West Trinity Lane and commercial corridors in Madison and Antioch.

Update (5:50 p.m.): After plans to cut down the trees were met with widespread outrage, Mayor David Briley has announced they will be removed…

Very few regulations were in place when the NFL planned to cut down 20 mature cherry trees on First Avenue ahead of the 2019 NFL Draft on Broadway. Butch Spyridon — then the city’s tourism kingpin as the head of the Nashville Convention & Visitors Corp — quickly brokered an apology from the NFL and publicized the league’s new relocation plan. Residents bristled at the episode, seeing it as another symbol of the city’s sacrifice to tourism.

Throughout our hourlong conversation, Ginger Hausser regularly refers to this short-lived semi-scandal as “Cherrygate.” A veteran of state and local government, Hausser became executive director of the Nashville Tree Conservation Corps in January.

“We are an exciting, vibrant, economically powerful city that continues to grow,” Hausser says. “This is a place people want to be, and the development community can make a lot of money here. That’s pressure on losing the canopy. For about 25 years, there was no real voice at the table externally saying we need to look at our canopy. A few really public removals of trees, like the [2019 NFL Draft] and Cherrygate, got the community engaged.”

The NTCC and the Nashville Tree Foundation are the two major tree nonprofits in Nashville. Their mission statements are interchangeable — promoting, planting, protecting, preserving — and they’ve grown to complement each other. The corps focuses on government efforts — a play to Hausser’s strengths, leveraging public money, drafting legal protections and administering grants. The NTF leans into education with its annual Big Old Tree Contest, in-school programs and arboretum designations.

“Our program — Tree Buddies — starts with helping kids just notice the trees are there. Recognizing that they’re alive, they change colors and they drop little acorns that are actually their seeds,” says Caroline Willett, the outreach coordinator at NTF. “Mostly they just like going outside.”

Both organizations work with Root Nashville, a city-funded project launched under former Mayor David Briley that aims to plant 500,000 trees in Nashville by 2050. The Cumberland River Compact oversees Root, which has 60 trained neighborhood tree captains across Davidson County. The captains liaise between Jason Sprouls, Root’s campaign manager, and residents who want to plant a tree.

As of this month, Root has planted 50,000 trees since the first young oak went in at Metropolitan Interdenominational Church six years ago.

The first tree planted by the Root Nashville campaign

“It’s a beautiful tree and a wonderful gift,” says Edwin Sanders II, the church’s founding pastor.

Before his congregation built its current home on 11th Avenue North in 1981, they would worship outside in a nearby park on sunny days. In a photo dated Oct. 10, 2018, commemorating the planting, Sanders stands with Sizwe Herring, a legendary local environmental justice organizer who died in January of this year.

“Buena Vista, our neighborhood, it means ‘beautiful view,’” says Sanders. “We want to surround ourselves in that spirit.”

Sanders points to the athletic fields behind John Early Middle School, the church’s neighbor to the east; he remembers when the site was covered in woods. Nearly every residential lot on the block has been redeveloped. Through the brush, Sanders spots a backhoe grading a plot across the street.

No one wants to pick a fight against tree planting, a tangible and symbolic act of hope and optimism. Taken together, sustained tree reforestation can come to resemble communal healing.

“Everybody feeds off trees in a different way — for me, it’s reconnecting to nature, which helps me tap into a deeper creative space,” says Jaffee Judah, founder and leader of Recycle and Reinvest, a local nonprofit that runs a youth tree-planting program called Soil Soldiers. “For them, it’s like a form of therapy and rehabilitation. It’s healing. Our youth learn actual employment skills, but also build connections to the community, and grow their sense of belonging.”

The tree canopy’s survival depends on spreading this gospel. Nashville’s high canopy standards for public land go only so far in a county dominated by private property. Most wooded lots belong to individuals who choose what to keep and what to fell. According to Nashville Tree Conservation Corps’ Hausser, straying too close to the property line could risk preemptive legislation from the state. During this year’s Tennessee Urban Forestry Council conference, Metro Water’s urban forestry coordinator Mike Jameson and Vice Mayor Henderson joined city attorneys Lora Barkenbus Fox and Tara Ladd to discuss the latent litigation threat. The Nov. 13 panel discussion was titled “The Lorax’s Dilemma.”

“Between toxic court decisions construing tree ordinances as unconstitutional takings, pervasive risks of preemption, and inherent difficulties enforcing tree regulations, the message from academia is to focus on incentives,” Jameson tells the Scene during the conference. “Everything from tax exemptions for tree canopies to density bonuses to expedited permitting.”

A recent federal court case looms large in the tree legal space: F.P. Development sued Canton, Mich., over tree protections imposed by the city in 2006. The company argued that local tree preservation laws violated its private property rights. The 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, which includes Tennessee, sided with plaintiffs in October 2021. In the case, a strong legal signal for municipal tree protections, the landowner compared the city of Canton to the British Crown on the eve of the American Revolution. The Texas Public Policy Foundation and the Cato Institute, two significant libertarian groups, argued the case for F.P. Judges ruled for the plaintiffs in part because the city didn’t demonstrate “rough proportionality” — that is, trees’ positive impacts on the environment did not seem to outweigh costly private penalties for removal. Jameson says he expects new legislation in the statehouse next year that uses tax and permitting incentives to promote tree conservation on private property.

TreeSavvy’s Adrian Wagner dismantling a hackberry

“Trees are not your private property,” says Adrian Wagner, Mike York’s colleague at TreeSavvy. “They do not care about property lines, especially the ones that have been there for 400 years. We just have to get past that idea. You just happen to have a house that’s nearby. You can choose to work with them, and they will make your life safer and more enjoyable.”

The day before speaking with the Scene, Wagner spent the day in a 60-foot hackberry. The tree had split near its center, a rupture that prompted owner Janet Lanier to call TreeSavvy’s York. (He recommends landowners consult with an arborist every few years about large trees near their homes.) With sawdust flying, Lanier and her two golden retrievers watched the tree come down piece by piece.

Wagner harnessed, then severed, thousand-pound chunks of trunk, canopy and large branches (which he refers to as “picks”). As the “climber,” he ascends into the canopy, relying on experience, ropes, his chainsaw, an instinctive grasp of physics and a crew of four — including a crane operator — to dismantle the hackberry in pieces. The crane slowly lowers each to the pavement, where York and others wait with chainsaws. Over the course of hours, the tree disappears into a wood chipper.

Wagner’s East Nashville home is decorated with ficus and bonsai trees. He uses these small models to point out branch structure and mimic incisions as he describes the process of taking down a mature tree.

Across the street, Wagner points to a younger Bradford pear — an invasive flowering species on the city’s no-planting list — and an older hackberry. Both had been “topped” during their lives, an outdated process of paring back a tree by lopping off its strong central branches. Small flowering trees can respond well, but topping permanently deforms big trees like the hackberry. A branch structure dominated by these offshoots makes the tree geometrically unstable, weak, unhealthy and unsafe.

“It couldn’t be structurally any more dangerous than it is right now,” Wagner says, pointing through the rain. “Twenty-five years ago, there was no management, just a one-size-fits-all solution to tree work that has degraded the entire canopy. They start to fall apart, and a kind of hysteria sets in. When storms come through, people get scared and preemptively take down their trees. It just becomes this downward spiral as nature disappears.”

Shoddy work poses immediate threats to residents and taxpayers. Topped trees and poorly managed brush create weak ecosystems, forcing avoidable future cleanup work. It’s a lucrative industry, Wagner says. To his trained eye, the “buzzcuts” he sees along Ellington Parkway and in Shelby Bottoms mean wasted taxpayer dollars on unnecessary, ineffective tree work.

“I think if we focused as much effort on keeping the trees up — doing the right kind of pruning at the right time, not topping them as we do — as we do planting new trees, we wouldn’t have to plant as many new trees,” Wagner says. “One way might be a fund to help people manage their trees who don’t have the financial ability to do that. I think we just gotta slow down. It’s like trying to get to Mars or something, and forgetting we’re on Earth.”

Kay Quinn’s male Osage orange tree, Maclura pomifera, is growing sideways across the front lawn of her new home on Ashwood Avenue. The females are known for dropping bumpy green fruit about the size of a softball.

Osage orange tree on Ashwood Avenue

“The tree canopies the whole front yard,” Quinn tells the Scene. “It shadows everything. For many people that’s off-putting, right? And I thought that was where I was on it.”

She bought the house, and the tree, from its longtime owner in May. The tree had fallen decades ago and become a kind of neighborhood folk symbol. In the interest of a smoother deal, the seller’s real estate agent put in a clause that the seller would pay for its removal upon closing.

“But then you kind of get to know the tree, and I bonded with it,” remembers Quinn. “This tree fell, it has lived, and it is thriving. I could not cut up this tree. Once I realized it had to stay, I called the realtor, I told the seller, and we stopped that process.”

Today Quinn pays a tree service to regularly replace cylindrical supports to keep the Osage’s heavier branches off the ground.

“If it goes naturally, it will go naturally,” she says. “If it doesn’t — and it is thriving — I’ll just keep taking care of it. As its guardian.”

Treesavvy’s Adrian Wagner dismantling a hackberry