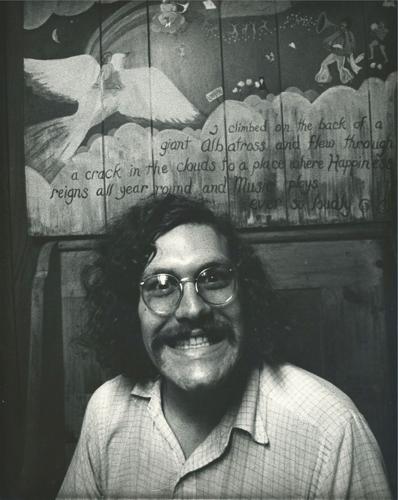

Stephen Cook Arwood

Beloved collaborator, practitioner of The Cowboy Way

After arriving in Nashville from his hometown of Oak Ridge, Stephen Cook Arwood trudged knee-deep into the heart of Music City’s cowboy culture, getting to work on numerous projects including his bestselling Don’t Squat With Yer Spurs On book series. For his most popular work, though, he traded his pen for a microphone, creating a number of TV programs, public radio shows, albums and a book for Western outfit Riders in the Sky. To the Riders, Arwood will always be known by his cowboy radio persona, Texas Bix Bender.

“He was a genuine human being, a kind heart,” said Douglas Green, aka the Riders’ Ranger Doug, after Arwood’s passing. “[He was] a lover of people, and so creative. He was just a very funny man.”

While Arwood became longtime buddies with all three core group members, he and Rider Fred LaBour, aka Too Slim, shared long writing sessions and unending fits of laughter. On Dec. 29, 2023, LaBour met Arwood for what would be their final lunch together. They reminisced about times on the radio, continued what LaBour describes as the “World’s Longest Running Football Bet” and reiterated their longstanding love for each other upon goodbyes. Arwood went home to his wife, Sally Moore Barton, before passing away later that night. —Bailey Brantingham

Melanie Safka

A legendary voice of pop

If you triangulate among three versions of Melanie Safka’s 1970 song “What Have They Done to My Song Ma” (released, as ever, under her mononym Melanie), you create a guide to that long-ago moment in pop culture. Safka’s version shows off her flexible, cutting — and self-mocking — voice. Ray Charles riffs on it on his magisterial 1972 version. Charles even changed the song’s name, rendering it as “Look What They’ve Done to My Song Ma.” Still, the most moving take on Sakfa’s song — and the biggest hit of the three — is The New Seekers’ 1970 single, which they deliver as subversive, commercial pop.

Melanie’s other hits — 1971’s “Brand New Key” and 1970’s “Lay Down (Candles in the Rain)” — sound great today. But the bluesy drag of “What Have They Done to My Song Ma” connects her with the left-leaning milieu of her early years in Astoria, Queens. Her mother sang jazz and blues and worshipped Billie Holiday. Melanie worked closely with her husband Peter Schekeryk throughout her career until his death in 2010. After his death she discovered she’d lost some of her most valuable songwriting royalties, but she continued to write songs and play the occasional show, including a brief 2021 appearance at Main Street Porch Fest in Hendersonville. Melanie had lived in the Nashville area since 2005 and moved to Hendersonville in late 2020. One of the great voices and songwriters of the era, Melanie died on Jan. 23. She was 76. —Edd Hurt

Tony Laiolo

The host with the most

Antonio “Tony” Laiolo died Jan. 31 at age 74. Born in Carmel, Calif., Laiolo had a love for music that progressed from studying piano and tuba in primary school to a fascination with the guitar. He found his calling in songwriting, and in 1981, he settled in Music City. During his 42 years here, he raised his family; he spent extensive time with McCabe Park Little League, coaching his daughters’ softball teams. He also served as a substitute teacher in local public schools and worked in advertising at Ericson Marketing, eventually launching Tony Laiolo Enterprises, his own independent communications firm.

While he never became a hit songwriter, Laiolo was a fixture in Nashville’s music community as he organized and participated in countless writers’ rounds, and from 2014 to 2020, he shared his humor, warmth and talent as host of Uncle Tony’s Townhouse at Brown’s Diner. Laiolo’s legacy lives on through his music, his family and the many lives he touched. —Jayme Foltz

Toby Keith

Exceptional singer, complicated man

Toby Keith was one of the most popular country singers of the past 30 years: Almost half of his 41 Top 10 hits made it to No. 1. He was a 2015 inductee into the Songwriters Hall of Fame and an often-underrated singer. His unfussy vocals and storyteller’s phrasing, plus his generous good ol’ boy tone on hits like “I Love This Bar,” landed like a modern Bobby Bare.

At the same time, Keith was, to put it gently, complicated and difficult. He cultivated a visceral sense of grievance in nearly all of his best-known numbers. Sometimes those beefs centered, infamously, around politics and the military or, less often and less explicitly, on class prejudices. Most often, though, they were gender-based and — to his credit and our benefit — songs such as “How Do You Like Me Now” (country radio’s biggest hit in 2000) and “I Want to Talk About Me” were played at least somewhat for laughs.

It was hard to feel generous toward Keith’s abhorrent responses to 9/11. His “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American),” a full-throated call for revenge, and the Willie Nelson duet “Beer for My Horses,” about the good old days when lynching parties had after-parties, embraced the worst of America. These were embraced by America in return, with both records crossing over to the pop charts.

It’s a straight line from Keith’s cruel anthems to the work of Big & Rich and Montgomery Gentry — who seem to split between them the joking and earnest halves of Keith’s persona — and from there to contemporary cultural bullies like Jason Aldean. Keith’s role as an accelerant in that progression will be his legacy, no matter how memorable and fun his earlier singles were. —David Cantwell

Roni Stoneman

Banjo heroine, Hee Haw cast member

Roni Stoneman was one of 23 children born to Hattie Stoneman and bluegrass musician Ernest V. “Pop” Stoneman (only 15 of whom reached adulthood) and was the banjo player in The Stoneman Family, which billed its vaudeville-inspired live shows as “The Rompin’, Stompin’, Pickin’, Singin’ Stoneman Family!”

In 1957, Roni’s instrumental version of “Lonesome Road Blues” made her the first woman to play modern bluegrass banjo on a phonograph record — a compilation album of three-finger, five-string banjo numbers in the style popularized by Earl Scruggs. In 1967, the group was named CMA Vocal Group of the Year, and when her father died in 1968, Roni Stoneman broke off to pursue a solo career. The family band’s live shows surely prepared her for the role that brought her adulation and fame as a mainstay cast member of the nationally broadcast prime-time country music variety hour Hee Haw.

She not only played banjo and sang but made her mark as a down-home country comedian in the style of Minnie Pearl. Her most enduring character on the show was the gap-toothed “ironing board lady” Ida Lee Nagger, a beleaguered housewife whose feckless husband never lifted a finger to help. It was — said Stoneman, who was five times married and divorced — a case of art imitating life. Roni and her sister Donna Stoneman, who played mandolin, continued to perform into the 2020s, and both were inducted into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame as part of The Stoneman Family in 2021. Donna is the last surviving member. —Kay West

Emily Bradley

Party starter, friend to many

Emily Bradley, 44, was an OG head — a Nashville raver and party promoter whose roots stretched back to the days of shell-toes and oversized polo shirts, when promoting parties meant putting flyers in hands as the sun rose and the party favors lost their potency. It meant being everywhere, all the time. It took bravery, charm and commitment, and is often invisible work in the eyes of history. But those folks — the ones who shoved a handbill into your paw as light dawned on your loose-marbled head — built the networks and created the close-knit dance music community we have today. Analog-era promotion was an art form in itself, and Bradley a fondly remembered practitioner. When she was reported missing in February, it sent shivers through the scene, and the network she helped build came together. When her body was discovered in Whites Creek weeks later, the outpouring from the typically upbeat dance music community was a flood of grief and anger. Her ex-boyfriend has been indicted for second-degree murder and is being held awaiting trial. —Sean L. Maloney

CJ Flanagan

Outlaw chronicler

Photographer and outlaw country community pillar Catherine “CJ” Flanagan died at 76 in March, leaving behind a rich legacy of stories and images that paint her as a one-of-a-kind character and friend to musical luminaries like Waylon Jennings and Billy Joe Shaver. Born in Washington, D.C., in 1948, Flanagan was one of nine children. Her time in Nashville found her growing close with artists like Cowboy Jack Clement and documenting pivotal moments of the outlaw country movement, like when Clement hosted Charley Pride to record new music at his Cowboy Arms Hotel and Recording Spa.

As a photographer, she captured images of Jennings, Johnny Cash, Townes Van Zandt and many more iconic figures. Her obituary describes her as having been “very vocal” in “defense of her outlaw friends,” and she was allegedly banned from Brown’s Diner following an “especially loud argument” involving her pals. Thanks to those friends it was only a temporary ban, though, and Flanagan’s family and loved ones gathered at the famed establishment in September to celebrate her wild, colorful life. —Brittney McKenna

Malcolm Holcombe

Malcolm Holcombe

Singer-songwriter, mountain mystic

The first time I saw Malcolm Holcombe play, in the late 1990s, I was flabbergasted. He rocked back and forth on a folding chair dangerously close to the tipping point, eyes closed as if in a trance, the occasional strand of saliva hanging from his mouth, his scratchy yet melodious baritone croaking over his singular fingerpicked guitar work. His songs somehow straddled a line between down-home country storytelling and divine mystic visions — concise, vivid, poetic, resistant to easy interpretation.

He was deep in the throes of a notorious drug and alcohol habit at the time, teetering on the brink of oblivion. Still, the set was hypnotic and utterly transcendent. As I described Malcolm in a 2005 Scene story, he was “part troubled soul, part front-porch sage.” Eventually Malcolm left Nashville and returned to his roots in the mountains of Western North Carolina. Much to the surprise of his many friends, he somehow managed to right his rapidly sinking ship, giving up booze and drugs. He toured relentlessly and recorded an extensive catalog of consistently inspired music, often with longtime collaborators Jared Tyler or Ed Snodderly. The front-porch sage somehow wrestled the troubled soul to the ground, thanks in no small part to his beloved wife Cyndi.

I got to know Malcolm over the years. He’d occasionally call out of the blue, just to say hi or offer to bring me a bottle of his homemade hot sauce, invariably rattling off at least one or two of his hilariously offbeat backwoods aphorisms. (Check out his 2011 performance of “Becky’s Blessed” on YouTube, where he tells a tale about Mama and her Red Man tobacco: “Her fingers gets up to her lips and she could knock the eye out of a cow at 50 yards.”)

Malcolm Holcombe died on March 9 at 68. Despite battling aggressive cancer, he was recording and performing till the end. You can watch his final livestream from Feb. 25, with oxygen tank by his side, on YouTube. —Jack Silverman

Mark Rubel

Recording legend, beloved teacher, Blind Rivet

Long before he came to Music City, Mark Rubel was already highly regarded as a recording engineer and producer, as well as an educator at Eastern Illinois University and staunch supporter of the local music community in Champaign, Ill. He was well-known for helping Champaign rockers Hum craft their influential stunner Downward Is Heavenward at his Pogo Studio; he launched the business in 1980, the same year he and friends started a rock band called Captain Rat and the Blind Rivets that remains an area institution. Other studio clients ran the gamut from Alison Krauss to Ludacris to Fall Out Boy to Adrian Belew.

Rubel struck up a friendship with John McBride, husband of country star Martina McBride and founder of the world-class Blackbird Studio, who offered him an opportunity he couldn’t resist. In 2013, Rubel and his wife Nancy moved to Nashville, where Rubel took on building the Blackbird Academy recording school from the ground up (while still operating a new iteration of Pogo). The academy is known for values that Rubel is remembered for: the pursuit of excellence and the recognition that you get the best out of people by treating them kindly. The Goffin & King Foundation (that’s Gerry Goffin and Carole King) has organized The Mark Rubel Memorial Fund in his honor. —Stephen Trageser

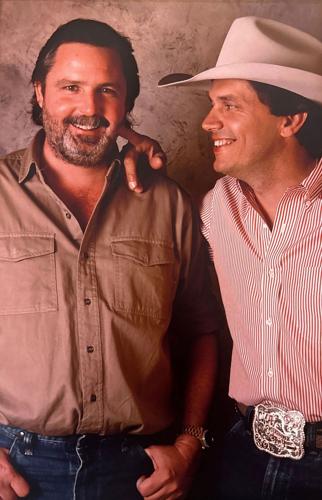

Erv Woolsey and George Strait

Erv Woolsey

Confidant, advocate, legendary artist manager

George Strait was not Erv Woolsey’s only client, but Erv Woolsey was George Strait’s only manager — a relationship that lasted more than four decades, and went far beyond business. Both Texans through and through, they were men of few words, and men of their word. Woolsey’s entire career was spent in the music business, and he worked in regional record promotion before moving to Nashville in 1973 for ABC Records’ newly opened country division. At the same time, he and his wife Connie owned The Prairie Rose in San Marcos, Texas. There he first saw Strait perform in 1975, and regularly booked the young, charismatic traditional country singer.

In the early ’80s, Woolsey was named VP of promotion at MCA Records, and convinced label head Jim Fogelsong to sign Strait. His debut single “Unwound” rocketed out of the gate, and a superstar was born. In 1984, Woolsey left MCA to officially manage the singer; they signed a contract at the time, and never signed another. Woolsey launched the Erv Woolsey Agency and was as loyal to his small staff as he was to his clients, a roster that included Clay Walker, Dierks Bentley, Lee Ann Womack and Ronnie Milsap. He opened Losers — a laid-back hole-in-the-wall just outside Music Row favored by publishers, producers, songwriters, musicians and the great, late Titans quarterback Steve McNair — and had his own designated seat at the bar.

It was rare to see Strait without Woolsey nearby: on the road, in the studio, at awards shows and on the set of Pure Country, the 1992 major release film Woolsey negotiated for his client to star in. Strait was well-known for his refusal to live in Nashville and his aversion to doing press; his friend always had his back.

Woolsey’s celebration-of-life service was held in the CMA Theater at the Country Music Hall of Fame. Onstage, an all-star band of studio musicians backed Jamey Johnson, Lee Ann Womack and finally Strait himself. He struggled to make it through one of his signature hits, “I Can Still Make Cheyenne,” a fiddle-drenched rodeo-cowboy ballad co-written by Aaron Barker — and Erv Woolsey. —Kay West

Norah Lee Allen

Singer’s singer

Norah Lee Allen was married for 54 years and eight months to country music superstar Duane Allen, the lead singer of The Oak Ridge Boys since 1966. Never did his fame deter her from her work, diminish her impact or dim her light. She began singing onstage with her family’s gospel group as a child, touring with them for 17 years before being hired by The Chuck Wagon Gang in 1968. She and Allen married in 1969, and she moved to Nashville, where she first worked for Benson Publishing. Her exceptional talent shone through on their demo tapes, and she was in demand for background session work with country, bluegrass and gospel artists.

That versatility led to her career-defining role as a 40-year member of the official Grand Ole Opry background vocalists, known first as the Carol Lee Singers, then the Opry Staff Singers. Saturday night after Saturday night (and often Fridays and Tuesdays) the quartet mastered the arrangements for dozens of songs, remained onstage through the entire show, perched on tall stools during breaks, then stepped in unison to their microphones to accompany that evening’s Opry legends and guest artists. They put the same effort into settling the nerves of a small-town teenager making their Opry debut as they did the biggest names in all genres of music, performing for thousands of fans in the building and millions on radio worldwide. —Kay West

John “Buck” Wilkin

Ronny Dayton

Songwriter-guitarist John “Buck” Wilkin of Ronny & the Daytonas fame passed away on April 6 at age 77. “He was one of Nashville’s unsung trailblazers,” says pop-rocker Bill Lloyd, who became friends with Wilkin in the latter part of his life.

The son of songwriter Marijohn Wilkin, he had already made a name for himself by the time his family moved to Nashville in 1958. At age 8, he began appearing on the Ozark Jubilee alongside classmate Brenda Lee and was often billed as “The Little Boy With the Big Guitar.” Wilkin entered the national spotlight as Ronny Dayton of the surf-rock group Ronny & the Daytonas. The group released two albums in the mid-’60s that yielded a pair of Top 40 hits — the million-seller “G.T.O.,” which reached No. 4 on the Hot 100 in 1964, and “Sandy,” which went to No. 27 in 1966 — and three other chart singles, all of which were written or co-written by Wilkin. In the early ’70s, he recorded a pair of albums under his own name and wrote a number of songs for Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie.

Wilkin’s songs have been recorded by a variety of artists, including Kris Kristofferson, Ray Charles, Odetta, Bobbie Gentry, Bobby Goldsboro, MC5 and Alex Chilton. He also worked as a session guitarist for Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, Joan Baez, Kinky Friedman and Steve Goodman, among others. —Daryl Sanders

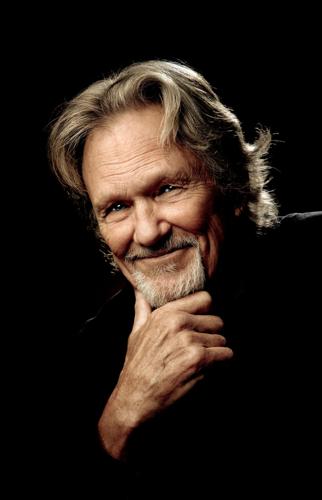

Kris Kristofferson

Kris Kristofferson

“A walkin’ contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction”

Kris Kristofferson’s biography includes so much that’s notable: He was a Rhodes scholar, a boxer, a helicopter pilot, a self-described peacenik who spoke truth to power, a movie star (who won a Golden Globe for his 1976 performance in A Star Is Born) and a family man. But his songs are poetry and prose tuned perfectly to the notes they paired with. When he was in the Army, the music of Bob Dylan made him believe becoming a songwriter would be a “respectable ambition.” Dylan himself later said that Kristofferson was responsible for shaping a new era in Nashville music.

After Kristofferson had been in Nashville a few years, Ray Stephens and Johnny Cash both released recordings of his “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down.” Now a revered classic, this piece by a songwriter who was then a relative unknown became the Country Music Association’s Song of the Year in 1970. Also in 1970, Kristofferson recorded that song (and other gems like “Me and Bobby McGee”) on Kristofferson, the first of more than 20 albums.

In the mid-1980s, he was part of the supergroup The Highwaymen, alongside Cash, Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson. At Nelson’s 90th birthday party in 2023, Kristofferson gave one of his final performances, singing “Loving Her Was Easier” with Cash’s daughter Rosanne.

“I’ve never known anyone as authentically themselves as Kris,” Rosanne Cash wrote in an article for Rolling Stone. “His very thoughts had an armament of courage.” —Nicolle S. Praino

Larry Garris

Corner Music founder, working musicians’ friend

As a college student, North Carolina native Larry Garris channeled his fascination with music into a job as a regional rep selling Aria guitars to music stores all across the Southeast. When he got his fill of traveling, he used his extensive hands-on knowledge to open the first iteration of Corner Music in his new hometown of Nashville in 1976. In the early 1980s, the store moved from Berry Hill to what’s now called 12South — convenient to Belmont University and the studios of Music Row — and more recently relocated to the East Side.

In a 2020 video interview with Guitar.com, Garris describes how he was bowled over by the exceptional musical talent in Nashville. Despite serving an array of stars and future stars over the years — and even employing a few, like Brad Paisley — he kept the business’s focus on gear and service that session and touring players came to rely on. “We position ourselves as a tool store for working musicians,” Garris said. “It goes back to the old Chet Atkins joke. A guy says, ‘That’s a great-sounding guitar!’ And Chet puts it down and says, ‘How’s it sound now?’” Garris died of cancer in May at 75, leaving behind his family, friends and staff as well as generations of grateful musicians. —Stephen Trageser

Pat Rolfe

Publishing power player, Music Row trailblazer

In 1966, Pat Rolfe got a phone call that changed her life. On the line was Lamar Fike, a member of Elvis Presley’s famed inner circle known as the Memphis Mafia. Fike was working at Hill & Range publishing, which controlled material recorded by The King, and he asked Pat to come on board. She said yes and began a career that took her to the top of Music Row. In 1972 she was named general manager and became one of the first women to head a major publishing company on Music Row. Chappell Music purchased Hill & Range in 1975, and Pat stayed on through a remarkable run that saw the company named ASCAP Publisher of the Year seven times.

Pat rose to the position of vice president and held that post until 1987, when Warner Bros. Music purchased Chappell. Connie Bradley, the longtime ASCAP Nashville head, snapped Pat up to serve as her director of membership relations. During Pat’s 23 years with ASCAP, she rose to vice president and brought in a full house of writers including Hillary Lindsey, Josh Kear, Chris Tompkins, Gerry House, Dierks Bentley, Brad Paisley and Wynonna.

With publishing colleague Judy Harris and record label executive Shelia Shipley Biddy, in 1991 Rolfe created SOURCE, an organization focused on fostering relationships and opportunities for women in the entertainment industry. Rolfe, who fiercely championed and generously mentored multiple generations of women in the business, was inducted into the SOURCE Hall of Fame in 2012. —Kay West

Jack Kingsley

Guitarist, songwriter, composer

Music was more than just a vocation for Jack Kingsley. It was his chosen language. Born John Michael Kinsella in New Jersey, he was raised and educated in Venezuela and Brazil, and often credited that early immersion in South American cultures for his versatility as a musician. He spent many years in the Boston music scene before moving to Nashville in 2011.

In 2016, Kingsley composed a song for Nashville Shakespeare Festival’s marvelous production of The Comedy of Errors, and played in the show’s “Jailhouse Band.” He also provided original music for Hamlet in 2018 and would go on to co-produce and contribute to The Music of the Nashville Shakespeare Festival — a beautiful album featuring songs from various shows and showcasing the talents of David Olney, John Hadley, Stan Lawrence, Lari White, Rolin Mains, Natalie Bell and more.

“Jack spoke English, Spanish and Portuguese fluently,” says Denice Hicks, Kingsley’s devoted partner and longtime artistic director for NSF. “But when thyroid cancer took his voice in 2020, he relied on his fourth language — the guitar. Through his music, he spoke volumes about the love he lived until his dying day. He loved teaching English language learners and shared his guitar skills with many students. He lived and loved with all his heart, and left a legacy of enrichment for all who knew him or heard him play.”

Kingsley died June 3 at 59. —Amy Stumpfl

Jon Wysocki

Drummer, modern-rock standard-bearer

Jon Wysocki, founding drummer of the rock band Staind, passed away earlier this year. He was 53. Wysocki’s rhythmic precision and passion helped define the sound of modern rock. His contributions spanned from Staind to his later work with Soil, Save the World and most recently Nashville band Lydia’s Castle.

Born in Westfield, Mass., in 1971, Wysocki joined Aaron Lewis, Mike Mushok and Johnny April in 1995, and his forceful playing helped propel Staind to worldwide fame. “From practice in Ludlow, Mass., to touring around the world,” reads a note on the band’s Instagram account, “Jon was integral to who we were as a band. Our hearts go out to Jon’s family, and fans around the world who loved him.”

Nashville became Wysocki’s creative home in recent years, and he left a lasting impression on the city’s music scene. He was more than a friend to many — his kindness and “infectious laugh” brought warmth to everyone he encountered, family and fans alike. He is survived by his fiancée, son, parents and sister. —Jayme Foltz

Mary Sack

Mary Sack

Artist manager, do-gooder, force of nature

To say Mary Sack came into my life is like saying a tornado dropped by for a visit. She was a walking triple espresso, knew the music business inside and out, could talk the chrome off a doorknob — and if she was in your corner, you truly had somebody in your corner. In our time together, she mainly managed David Olney and me. But not one to limit herself to only two full-time jobs, she worked in differing ways with many other artists. She was also the force of nature behind the annual Get Behind the Mule benefit. Then she was in the clubs four or five nights a week — and she slept every other Thursday. We parted company business-wise but stayed friends, and at one of my gigs last year she offered an offhand mention that she had Stage 4 lung cancer — with a smile. I’ll never forget what she said. “It’s only overwhelming, that’s all.” Sack, you were loved, you are missed, and I’m not entirely convinced that you’ve completely gone away. Our loss is only overwhelming, that’s all. —Tommy Womack

Buzz Cason

Buzz Cason

Nashville pop trailblazer

James E. “Buzz” Cason passed away June 16 at 84, leaving behind a legacy as a pioneering pop producer, publisher, songwriter and studio owner. “Buzz always had both feet in the world of pop and rock music,” says producer-engineer Brent Maher, who recorded his first master sessions with Cason. In the mid- to late ’50s, Nashville native Cason was a member of pioneering rock band The Casuals. As a solo artist, he scored a pop hit (“Look for a Star”) in 1960 under the name Garry Miles. He also was a member of Ronny and the Daytonas, co-writing their 1966 hit “Sandy.” But Cason made his biggest mark as a publisher and producer.

Some of the hit songwriters Cason helped develop as a publisher include Bobby Russell, Mac Gayden and Jimmy Buffett. Among his first hits as a producer were a pair of songs written by Gayden — Clifford Curry’s R&B hit “She Shot a Hole in My Soul” and Robert Knight’s pop smash “Everlasting Love,” which Cason co-wrote. In 1970, Cason opened the first studio in the Berry Hill neighborhood, Creative Workshop. It soon became a hot spot for pop and rock sessions and remains so to this day. “He was such a huge influence on me as far as how he conducted his sessions,” Maher says. “He would have a firm concept of what the record was going to be while giving every musician in the room as much latitude as they wanted.” —Daryl Sanders

Zachary Boetcher

Father, rapper, inspirer of greatness

When he picked up the mic, Zachary Boetcher took on the moniker K.I.N.G. the MC. The acronym stands for “Knowledge Inspiring New Greatness,” and that’s something he took to heart in every aspect of his life. Beginning at a very young age, he developed superb skills in spoken-word poetry and rapping, showcased on his 2019 album The Good. The Bad. The Ugly. and its Part 2 follow-up from 2020. He pulls off the challenging feat of delivering eloquence articulately at speed, especially in the standout track “Crazy World,” in which an overwhelming array of social ills test the faith that was so important to him.

Boetcher is remembered even more for how much he gave of himself to his family and others around him. A devoted father of five, he was a beloved youth softball coach, known to go to great lengths to support that community and to nurture kids in ways that went far beyond the mechanics of the sport. He leaves behind a large and loving family as well as a wealth of people he made to feel like family. —Stephen Trageser

Joe Scaife

Producer, publisher, song matchmaker par excellence

If “Achy Breaky Heart,” Billy Ray Cyrus’ 1992 crossover megahit, has ever gotten stuck in your head, you can thank (or blame) Joe Scaife. The line-dance sensation was on Cyrus’ debut album Some Gave All, co-produced by Scaife and Joe Cotton. The song had been turned down by The Oak Ridge Boys and previously released, to no note, by the Marcy Brothers as “Don’t Tell My Heart.” Scaife brought it to Cyrus, and it rocketed to No. 1 on the country charts, blasting Cyrus to mullet-topped fame.

Scaife was known for recognizing potential in unknown performers and pairing them with the perfect country songs. Producing, engineering and publishing were in his blood; he spent much of his youth in his father Cecil Scaife’s Hall of Fame studio. He attended Belmont University and majored in music engineering and recording. Post-college, he and his wife Danielle ran Joe Scaife Productions and four publishing companies. Scaife’s name can be found as producer, publisher and/or engineer in the liner notes of songs and albums by Alabama, K.T. Oslin, Montgomery Gentry, Lionel Ritchie, Loretta Lynn, Shania Twain, Glen Campbell, Gretchen Wilson, Lou Rawls, Vince Gill, The Oak Ridge Boys, Toby Keith, Reba McEntire, Rhett Akins, Charlie Daniels, Trace Adkins and many more.

Joe Scaife’s formal education at Belmont inspired his father to advocate for the establishment of a school of music industry there, which evolved into the Mike Curb College of Entertainment and Music Business, and Joe Scaife continued that support after his father’s death in 2009. —Kay West

Mary Martin

Artist whisperer

On July 4, Nashville lost one of its music industry mavens, whose legacy will carry on through the careers of artists like Van Morrison, Vince Gill and Bob Dylan. Grammy winner, glass-ceiling shatterer and all-around music industry virtuoso Mary Martin catapulted herself to the top of a male-dominated industry with her knack for nurturing the careers of established artists, as well as her eerily accurate eye for up-and-comers in country, folk and what we now call Americana.

Born in Toronto in 1939, Martin dove into the deep end of the bustling music-business environments in New York, Los Angeles and Nashville. Her determination helped her quickly climb the corporate ladder at companies like Warner Bros. and RCA. Martin’s career blossomed on account of her own self-determination. As a female music industry professional in the 1960s — when that glass ceiling was still shatterproof — Martin was driven by her supreme instinct. She was often crafty in executing her plans, demonstrated when she secretly hired country radio promoters for one of her budding discoveries, Emmylou Harris, after Warner Bros. refused to. This led to Harris’ first country No. 1.

Martin was awarded the Americana Music Association’s lifetime achievement award in 2007 and was honored by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in 2009 — both recognizing the deep roots she placed in Nashville. —Bailey Brantingham

Joe Bonsall

Oak Ridge Boys MVP, multiple Hall of Famer

Joseph Sloan Bonsall Jr. was just 25 years old when he became the newest member of the then-30-year-old vocal group The Oak Ridge Boys in 1973. The fast-talking Philly native who never lost his accent or his fanatic passion for the Phillies would seem an unlikely match for a Southern gospel group. But he had spent many years with The Keystone Quartet, and it was a smooth transition for him.

With his great mass of black curls and bushy black mustache (both later gray), Bonsall bounced onto the stage as a kinetic ball of energy, from first song to encore, through all the early years of grueling tours and well into his 60s and early 70s. His clear tenor voice was the signature on many of the Oaks’ biggest hits, including “Elvira,” “American Made” and “Bobbie Sue.” Bonsall often served as spokesperson for the group, respectful of the media and appreciative of their work. He was also an author, writing 11 books, including his deeply introspective and grateful memoir I See Myself, published in 2023.

In 2019 Bonsall was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS) but continued performing, often seated on a stool, until he was forced to retire in early 2024. He was unable to participate in the group’s American Made Farewell Tour. Bonsall was a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Gospel Hall of Fame, the Vocal Group Hall of Fame and the Philadelphia Music Hall of Fame. Only membership in the Baseball Hall of Fame eluded him. —Kay West

Peter Collins

Producer, “Mr. Big”

When Peter Collins died of pancreatic cancer in late June, Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls wrote, “Peter Collins was the producer who raised the musical bar for us and showed us how to be musically ambitious.” She spoke for many of the artists who worked with him.

Collins was a native of Reading, England, and got his start in the record business in London in the mid-’70s, landing a record deal with Decca as a singer-songwriter. He soon realized he was more interested in production than being an artist, and took a job with the label as an assistant producer. He moved to Nashville in 1985, and he found his greatest success with Music City as his home base, producing significant albums for a diverse array of recording stars from rockers like Rush (whose members called him “Mr. Big”), Queensrÿche and Bon Jovi to singer-songwriters such as the Indigo Girls, Jewel and Nanci Griffith.

“Peter was just magical in how he did things,” says engineer and mixer Paul David Hager, who worked extensively with Collins. “His brilliance was taking a band that had a sound, not getting in the way of what they sounded like, but focusing their sound better.”

Joe Baldridge, who mixed Jewel’s No. 1 hit “You Were Meant for Me” for Collins, echoes that point: “His genius was he could focus a track for an artist without making them feel artistically encroached upon.” —Daryl Sanders

Randy Davidson

Guiding light in record retail

Randall Lee Davidson Sr. put his music business savvy to work in multiple aspects of record sales and saw it bear fruit many times over. Born and raised in Nashville, Davidson co-founded Central South Music Sales in 1970. The company’s successful distribution business expanded to include 85 Sound Shop record stores and a slew of Music 4 Less record outlet shops. The firm served as wholesaler to more than 1,000 independent record stores and serviced more than 10,000 jukeboxes, and it became one of the largest privately held companies in the city.

Among other endeavors, Davidson was part of the group that launched radio station WHVT, also in 1970; the station changed hands several times and has been known and loved as 92Q since 1984. From 2002 until his death in July, Davidson was CEO of Central South Distribution, one of the first companies to distribute gospel records nationwide, and one that has paid special attention to helping artists control their own music catalogs. —Bailey Brantingham

David Allen Loggins

Country-pop balladeer

Dave Loggins, who grew up in East Tennessee and was second cousin to fellow songsmith Kenny Loggins, penned more than five decades’ worth of much-loved songs and garnered a reputation as one of Nashville’s most esteemed songwriters. He had a knack for sentimental ballads, and Three Dog Night had a smash with his “Pieces of April.” Among songs he recorded himself, his lone pop hit was 1974’s “Please Come to Boston,” which explores complexities in long-distance relationships; it secured him his first of four Grammy nominations, and Joan Baez and Willie Nelson are among the luminaries who’ve covered it. In interviews, Loggins credited “Boston” to divine inspiration. He was also inspired by the natural beauty of the Augusta National Golf Club to write “Augusta.” Though the song’s lyrics are seldom heard, he also wrote the music, and the instrumental track has been the theme of the Masters golf tournament since 1982.

He applied his fine-tuned sensitivity to songs for country artists, like Tanya Tucker’s “You’ve Got Me to Hold Onto,” Johnny and June Carter Cash’s “Where Did We Go Right,” Reba McEntire’s “One Promise Too Late” and Kenny Rogers’ No. 1 hit “Morning Desire.” Though Loggins did not write “Nobody Loves Me Like You Do,” he won a CMA Award for his 1984 duet on the song with Anne Murray. Among 25 ASCAP awards, he was named the organization’s Country Songwriter of the Year in 1987. He was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1995. Loggins died July 10 at Alive Hospice. He was 76. —Madeleine Bradford

Summer Shakespeare Festival; Kenny Dozier (left), Tom Mason

Tom Mason

Songwriter, actor, beloved pirate

In a city full of country music pickers and head-banging rockers, there are but few swashbucklers, and Tom Mason stood tall among them. A songsmith, musician and actor who died Aug. 31 at 65, Mason is remembered by the Nashville community as a joy-filled entertainer. Founder of pirate-themed band The Blue Buccaneers, the Minnesota native prided himself on his passion for nautical history and pirate lore, and his ability to turn it into a successful musical enterprise.

The Buccaneers toured the U.S. and beyond, playing the pirate festival circuit and garnering enough attention for Mason to be inducted into the International Pirate Hall of Fame. His renown in the community reaches further: He worked extensively with the Actors Bridge Ensemble and the Nashville Shakespeare Festival, taking on roles like Feste the Fool in Twelfth Night and even writing his own musical. His willingness to embrace fun and silliness is remembered fondly by many. —Katie Beth Cannon

Mark Moffatt

Producer, music businessman, mentor to Keith Urban

How does one record punk music without delving into pure chaos, sheer noise and unintelligible madness? Mark Moffatt answered these questions on “(I’m) Stranded,” wrangling the neurotic tendencies of Australian punk band The Saints into a phenomenally crafted 1976 recording. The producer, only 25 at the time, took their buzzsaw guitars and haywire vocals and channeled them into a studio setting, creating a wall of sound by double-tracking vocals and recording some instruments from the hallway outside the studio. In Brisbane, hundreds of miles away from The Clash or the Buzzcocks, Moffatt harnessed a distinctly Australian brand of punk.

Across his career, Mark Moffatt continued to produce Australian artists across genres, from Yothu Yindi, who incorporated Aboriginal tradition with pop music, to New Wave artists like Tim Finn. Moving to Nashville in 1996, he bridged the divide between Australia and Music City, developing Keith Urban’s career and mentoring his fellow Aussie. Moffatt was a founding member of the Americana Music Association, and through APRA AMCOS, he helped Australian artists license and distribute their music in Nashville. No matter the genre or style, Moffatt worked tirelessly to push his country’s music to the spotlight. —Ben Arthur

Deandre Haynes, aka DJ Svnny D

Deandre Haynes aka DJ Svnny D

A ray of sunshine in Nashville nightlife

Farewell to a person who was truly loved. I was blessed to have time to connect with someone so special. Deandre Haynes, aka DJ Svnny D, was not only funny, hungry, ambitious and motivated, he was also like a brother to me. After his passing I realized he had that same kind of impact on almost everyone he came in contact with. His energy was unmatched, his smile and laughter were contagious. That’s why the name “Svnny D” fit him so perfectly — he was a ray of light who would walk in a room and brighten it up with just his presence. He came to Nashville as a student not knowing that he would change the face of the nightlife scene and leave his mark on the city forever.

Deandre Haynes was a true one-of-one — there will never be another DJ Svnny D. Moving forward I promise to apply the same energy Svnny had for life to mine, and hopefully it will spread to my loved ones and to their loved ones, and Svnny’s energy will live forever. His untimely demise has left us brokenhearted, but even in the darkest times the sun still shines. So in the words of everyone’s favorite person, “PEACE, LOVE & BELLY RUBS,” yeeee!!! —@concretecapo, Small Axe Agency

Will Jennings

Literate lyricist

Producer Norbert Putnam will never forget when he first met hit songwriter Will Jennings, who passed away Sept. 6 at 80. It was at Quadrafonic Studios in 1971. “He came into my office and said, ‘I’m Will Jennings, and I’m from Tyler, Texas,’” Putnam recalled recently. “‘I’m a terrible musician, but I think I can write lyrics.’”

That turned out to be a monumental understatement, as the English professor turned songwriter would become one of the most celebrated lyricists in the history of popular music. Putnam and David Briggs signed Jennings to their publishing company Danor Music, and according to Putnam, Jennings “immediately wrote a hit for somebody.” A three-time Grammy winner, a two-time Academy Award winner and a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, Jennings penned six No. 1 hits, beginning with Barry Manilow’s recording of “Looks Like We Made It” in 1977. He topped the Billboard Hot 100 four more times in the 1980s, including a pair of hits he co-wrote with Steve Winwood — “Higher Love” in 1986 and “Roll With It” in 1988 — as well as Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes’ duet on “Up Where We Belong” in 1982 and Whitney Houston’s cover of “Didn’t We Almost Make It” in 1987. His final chart-topper came in 1997 with Celine Dion’s recording of “My Heart Will Go On.”

Jennings also penned hits for Eric Clapton, The Crusaders, Dionne Warwick, Tim McGraw, Jimmy Buffett and Diana Ross. B.B. King, Roy Orbison, Johnny Cash, Mariah Carey and Emmylou Harris are among the other artists who recorded his songs. —Daryl Sanders

J.D. Souther

J.D. Souther

Singer-songwriter, actor, honorary Eagle

Songwriters Hall of Famer and former Nashvillian John David “J.D.” Souther passed away at his home in New Mexico Sept. 17 at age 78. Souther, who has been called a principal architect of the Southern California sound, rose to prominence in the 1970s, co-writing some of the biggest hits for the Eagles, including a trio of No. 1s — “The Best of My Love,” “New Kid in Town” and “Heartache Tonight.” He also wrote a number of songs for Linda Ronstadt, including “Faithless Love” and “Prisoner in Disguise.”

Souther had success as an artist too, releasing a number of critically acclaimed albums. The title track from 1979’s You’re Only Lonely went to No. 1 on the Billboard Adult Contemporary chart and No. 7 on the Hot 100. He also teamed with Chris Hillman (The Byrds, The Flying Burrito Brothers) and Richie Furay (Buffalo Springfield) in The Souther-Hillman-Furay Band for two albums in the mid-’70s, with their eponymous debut reaching No. 11 on the Top 200.

Souther was also a part-time actor who appeared in films like Postcards From the Edge and the TV series Thirtysomething. He moved to Nashville in 2002 and became a beloved member of the community. He continued to write and record here, cutting a pair of studio albums including 2008’s If the World Were You, his first album of new material in 24 years. He also had a recurring role in the first season of the series Nashville.

“One of the greatest songwriters ever,” says artist manager Burt Stein, who first met Souther in the early ’70s. “I think the emotion and the feeling and the melodies in J.D.’s songs were second to none.” —Daryl Sanders

Owsley Manier

Owsley Manier

Exit/In co-founder, producer, artistic director

Exit/In opening in 1971 was a seminal moment in Nashville’s music history, and its founders Owsley Manier and Brugh Reynolds aren’t given enough credit for its impact. For the entire first decade of the venue’s existence, Owsley used his eclectic taste in music to guide his booking of the diverse range of bands that made Exit/In a destination venue. When Exit/In opened, there were surprisingly few options for watching live music in Nashville, and even fewer options for a musician to play. As a teenager Owsley was a member of the influential local band The Lemonade Charade, and from the very beginning the venue championed artists with its “listening room” concept. Less than a year in, Owsley teamed up with BMI’s Rick Sanjek to create Nashville’s first songwriter’s night.

Vector Management founder Ken Levitan recalled: “Owsley was a genius with programming, often combining local artists coming into their own with critically acclaimed national touring acts. Where else could you see John Hiatt opening for Billy Joel or back-to-back nights of Emmylou Harris and Jimmy Buffett? He also created a bar atmosphere where young people working in music could gather and not only discover new songwriters and artists but also learn the business. He did that for me. Most importantly, Owsley became a friend. It laid the groundwork for so much of what I did with my career.”

Exit/In became a countercultural center, acting as a movie house, featuring comedians and holding benefit shows supporting the local community — so many of the things we hold dear in local music today.

When I talked to Owsley in person during the past few years, his eyes would dance when retelling old Exit/In stories. But his association with music continued long after he left Exit/In in 1981. Over the following decades he continued as a promoter, mixing engineer and an artistic director and music video director. He also started the Winter Harvest record label in the mid-’90s and was executive producer on Steve Earle’s Grammy-nominated comeback Train a Comin’ in 1995.

“The older I get the faster I move,” he said to me in a 2022 email. “It’s to the wall right now, but let’s carve out a time to get together. It’s all part of my rock ’n’ roll dream.” We should all chase our rock ’n’ roll dream. —Stephen Thompson

Johnny Neel

Champion of the blues — and more

Multi-instrumentalist, vocalist and songwriter Johnny Neel made memorable contributions in many different settings. The blues were always at the core of his sound, although his songs were also recorded by rock, soul, country and pop musicians. He began writing and playing early, cutting his first single as a 12-year-old and getting regional airplay near his hometown of Wilmington, Del.

Neel, who passed Oct. 6 at 70, was a gifted soloist on keys and harmonica, and a fine, soulful singer. He was a Music City resident for more than three decades, making his first major impact here with his playing on Dicky Betts’ solo LP Pattern Disruptive. That led to joining Gregg Allman’s road band, and from there he’d become part of a reunited version of the Allman Brothers Band at the tail end of the ’80s. Not only did Neel perform on the group’s Seven Turns LP, but he also co-wrote the No. 1 hit “Good Clean Fun,” along with three other songs.

Neel was prolific in the 1990s and beyond. He wrote songs cut by Montgomery Gentry, Delbert McClinton and more; performed with the Allman Brothers, on his own solo albums, on Nashville studio sessions and in collectives like Blue Floyd; and ran both his Straight Up Sound studio and his Breakin’ Records label. In later years, Neel frequently returned to the blues, including with his group The Criminal Element. Among the highlights of their gigs around town: a phenomenal slot opening for Gary Nicholson and the Change in 2023 at 3rd and Lindsley. —Ron Wynn

Joe Dorn

Joe Dorn

Drummers’ drummer, brotherly mentor

“Is Joe in the back?” These five words have been uttered by countless drummers from across the globe — many times with undertones of desperation. They would have come into Fork’s Drum Closet, confident that a difficult repair would be carried out by one of the friendliest and most resourceful people on the planet.

Joseph Michael Dorn, a native of Clinton, N.Y., moved to Nashville in 2000 to further his musical journey. Growing up on bands like Deep Purple (his favorite drummer was Ian Paice) and King’s X, and possessing an inquisitive mind and endless curiosity, Joe developed an encyclopedic knowledge of music and craftsmanship that made him an integral part of the Nashville music community and Fork’s in particular. Joe performed in many live and recording situations with national acts, as well as up-and-comers. A staple at the Nashville Drummer’s Lunch, Joe would be there any time a new player moved to town. They were often introduced to Joe with a “You’re gonna dig this guy”; whoever was making the introduction was right.

Joe’s passion for graphic arts, model cars and hockey were always topics for conversation, and his ability to relate to anyone gave many in his life the feeling that he was the brother they never had. He also seemed to know all of the best places to eat, in which many of us had the opportunity to join in fellowship with him.

We will all miss our friend more than words can say, and there will be a hole in our community’s heart forever. We know you’re out there soaring, and looking down on us all and smiling. You did good for so many, and we’re all grateful to have known you. Godspeed Joey.

“El Tap?” —Dan Douchette

Pastor Darryl Frierson

Nashville gospel music hero

Gospel duos aren’t commonplace, and those consisting of twins less so. Nashville’s The Joy Boyz were standouts in every way, and the spiritual music community mourns the loss of the magnetic Rev. Darryl Frierson, who was one-half of the ensemble alongside his brother Donnie. Rev. Frierson passed in September at age 60. The Nashville-born duo made their debut in 1982. Though they were known to riff on their short stature, their powerful harmonies and solo vocal work made them an immediate hit on the gospel circuit.

In the mid-’90s, they shared a stage with The Gospel Keynotes, and a Baltimore Records representative was so impressed that he signed them to an album deal. A later signing to Malaco Records’ gospel imprint 4Windz yielded their signature record, 2011’s Stand Tall in the Lord. Cut live at Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church in North Carolina, the LP established The Joy Boyz as contemporary standouts with the dynamic, flamboyant style of classic quartet shouters.

Rev. Frierson was also an evangelist, with the Glenn Tabernacle United Primitive Baptist Church being his home place of worship. He was one of the first recipients of a Nashville Gospel Music Honors award in 2020 from the Nashville Gospel and Sacred Music Coalition. His memory and impact are now an established part of gospel legacy. —Ron Wynn

Kerstin Rupprecht

Uplifter in residence

Kerstin Rupprecht, a gifted photographer originally from Germany, left an indelible mark on the music community and everyone fortunate enough to know her. Kerstin moved here for her fiancé, Nashville musician Mike Bibbs (of the band Modern Convenience), but she had fallen for the underground music scene as well. As a visitor, she had filmed a documentary at Betty’s Grill in the late 2010s, reflecting her deep appreciation for the easy-to-miss creative zeitgeist outside of Nashville’s commercial music industry.

Kerstin’s enthusiasm for her friends’ artistic pursuits was unrivaled. She was the person who danced while everyone else had their arms crossed. She was 1,000 percent down to attend your dinky Monday night dive-bar show — and on top of that, she’d take photos making you look cooler than you had any right to. She uplifted, celebrated and truly believed in the people she cared about. Even her own artistic expression — the outlet through which she shone, her photography — was about others.

Kerstin was kind to her core, generous without hesitation, and joyful. Her fiancé, family, friends, and cats were her greatest treasures, and she made sure they knew it. In the tragic haze of losing her so young and so suddenly, her incredible spirit still shines bright. —Ziona Riley

Mike Martinovich

Music marketing magician

Like other exotic transplants to Nashville’s insular Music Row in its vinyl era, Mike Martinovich was likely greeted countless times with the rhetorical question, “You’re not from here, are you?”

The obvious answer was no. Of Serbian heritage, he was born and raised in St. Louis, graduated from the University of Missouri with a degree in political science and threw it all away to pursue a career in the music business. Starting as a sales representative for CBS in St. Louis in 1969, he spent the next three decades moving up the ladder and around the country, with promotions taking him to Atlanta, Cincinnati and eventually (as VP of merchandising) to CBS headquarters in New York City. In that role, he was instrumental in marketing such artists as Bruce Springsteen, Michael Jackson, Pink Floyd, Journey and James Taylor.

In 1989, he switched horses and went to Sony Records Nashville, where he worked the Martinovich magic for a stable of country stars that included Mary Chapin Carpenter, Dolly Parton, George Jones, Merle Haggard, Rosanne Cash, Patty Loveless, Rodney Crowell and Charlie Daniels. He had a special affinity for female artists, and a deep love for Tammy Wynette. As a manager, he developed the careers of several emerging artists, including Jason Aldean, but had the most enduring bond with torch singer Mandy Barnett.

Martinovich was a founding member of Sveta Petka Serbian Orthodox Church in Nashville, where the service was held in the Serbian language. His death was noted in every entertainment industry publication, but only the Serbian Times referred to him as he would have loved: “Majk Martinović.” —Kay West

Amelia White and Andy Rubin

Andrew Rubin

Itinerant music manager

It was always an unexpected surprise to run into Andy Rubin. Despite not officially living in Nashville, he managed several local bands and would somehow just appear at many last-minute gigs. You’d know he was there when you heard his laugh. So it was poetic that Rubin passed away unexpectedly at a music conference in November at age 59.

“Andy did his work with artists out of passion and love rather than financial gain,” says Amelia White, an East Nashville folk-pop singer who worked with Rubin for years. “In many ways, he was more like an artist himself, and that was sometimes hard on the business end, but on the spiritual, big picture, it was pretty great.”

White felt seen as an artist by Rubin, and … well, ready for the unexpected.

“At times, it felt magical, like the time after a gig in New York City with really low attendance [when] he whisked me off to Carnegie Hall to hear his mom Judy sing [in a choir],” White remembers. “It might be the best few hours we’ve ever had.” Later that evening, White sang for Judy and her friends.

Rubin championed women in music, in politics and in his personal life. He thought White should work with a woman producer and helped fund Love I Swore, which White made with Kim Richey and released earlier this year. In addition to White, Rubin championed woman-led acts including Hello June, Ashleigh Flynn & the Riveters and Lilli Lewis.

“He was a true advocate for independent musicians,” says Flynn. “He was the fan in the front row!”

Rubin loved everything about Nashville, except that Amtrak doesn’t run here and that The Wild Cow closed. He attended AmericanaFest annually, couch-surfing, staying up late drinking bourbon and talking about music, baseball or politics. When he realized he was coming up on his 13th fest, he named his showcase “Andy’s Americana Mitzvah.” He kept with the theme, throwing Andy’s Americana Mitzvah IV at Love + Exile in 2024.

Perhaps Mike Grimes says it best: “He was our people.” —Margaret Littman

George Ingram

Masterful mastering engineer, champion lacquer cutter, shepherd of dreams

The tonal characteristics of vinyl records and the high-quality tangible interaction they provide help remind us of all that music can be and can do. George Ingram started practicing the fine balance of art and science that is cutting acetate master discs — the first step in mass-producing vinyl copies of recorded sound — circa 1970 as an apprentice at Nashville Record Productions, a pioneer mastering facility that was independent of record labels. NRP founder Kenneth Place died just a few years later, and Ingram and a couple colleagues took over the business. When CDs reigned prior to the storied “vinyl resurgence,” this essential knowledge could have been lost if not for engineers like Ingram keeping it alive and passing it along to others like Wes Garland, his fellow engineer and partner in NRP since 2006.

Ingram had a warm sense of humor, a knack for staying cool under pressure, and a love of spending time with his family and taking motorcycle rides. Another credit on his extensive list was helping Third Man Records get their live-to-acetate program off the ground. Following Ingram’s death in December at 77, TMR co-owner Ben Blackwell posted a remembrance to Instagram. He recalled asking Ingram how many records he’d mastered; it took some time to put the estimate at over 10,000. “That’s ten thousand dreams brought to life,” Blackwell wrote. “Ten thousand visions fulfilled. Ten thousand chances to make someone’s day, put a smile on their face, earworm a melody in their head … it all starts with a record.” —Stephen Trageser

Larysa Jaye

Songsmith, mother, pathbreaker

Singer-songwriter Larysa Jaye was a longtime local music stalwart and a rising star associated with the Black Opry. Born in Missouri, the mother of four had Nashville roots that stretch back to Hillwood High and the alternative folk and R&B scenes of the Aughts and 2010s. Her songwriting tapped into the whole pantheon of Music City history — from Jefferson Street to Music Row to the Rock Block and beyond — in a way that was cosmopolitan when Nashville wasn’t, and she stayed down-home when this town’s britches got a little too big. Her songs are built from the connective tissue that holds genres together, makes them move, makes them jump.

She carved out a unique sonic space, brave and bold, that the rest of the world was just beginning to catch up to. Her dedication to the craft despite life’s travails landed her residencies on Lower Broad and at BNA, welcoming weary travelers with a stellar example of Music City’s social and artistic potential. The fact that the world seemed finally ready to embrace her artistic vision makes her sudden passing in a car accident all the more shocking and sad. Her voice and her energy, which had carved out a special place of respect among this city’s working musicians, will be sorely missed. —Sean L. Maloney

Remembering many of the irreplaceable Nashville figures we lost in 2024