Gov. Bill Lee’s reelection happened right on schedule. The Associated Press called the race at 7:02 p.m., two minutes after the polls closed on Nov. 8. Lee took the stage at his victory party in Cool Springs around 7:45 and walked off to “Rocky Top” 15 minutes later, wrapping up a tidy celebration around 8:30. Some lingered to watch Fox News election night coverage. By the official tally, Lee won his second term by 32 points — nearly 600,000 votes — over Nashville physician Jason Martin, marking a decade-and-a-half of Republican dominance in statewide political races.

Lee was elected as a political newcomer in 2018, forging a high road past current University of Tennessee President Randy Boyd, former U.S. Rep. Diane Black and then-House Speaker Beth Harwell in a Republican primary remembered for its attack ads. Lee Company, the regionally competitive home services company based in Franklin, has been the family business for 80 years and supplied natural name recognition. At times, the lines between HVAC commercials and campaign ads got blurry. Nashville-based Christian publishing house Thomas Nelson released Lee’s faith-heavy memoir, This Road I’m On, in May of that year. It centered largely on the trauma of losing his first wife, Carol Ann, in a horseback riding accident.

On the campaign trail, the future governor made it a point to stay above the fray. Lee took the Republican nomination with 37 percent of the vote. In the general, Lee trounced Democrat and former Nashville Mayor Karl Dean by 20 points, and has enjoyed a Republican supermajority in both legislative chambers for the four years since. Occasionally, Lee has butted heads with House Speaker Cameron Sexton and Senate Speaker Randy McNally, both of whom are expected to return to their positions in leadership in the upcoming legislative session. He’s faced no real threat to his position atop the state’s party hierarchy. While backing some of the country’s most hard-line policies on abortion and organized labor and overseeing some of the nation’s worst income inequality and health care access, Lee has cultivated a reputation as a benevolent pragmatist, faithful to free markets and God.

“The voters of Tennessee have rewarded him twice,” Scott Golden, chair of the state’s Republican party, tells the Scene a week after Lee’s reelection. “They are attracted to his genuineness. What you see is who he is.”

Gov. Bill Lee greets Jake McCalmon at The Factory at Franklin on the eve of the 2022 election

Teachers, parents and students across Tennessee’s more than 140 school districts await the effects of Lee’s efforts to overhaul the state’s public education system. Reagan-era economic beliefs still rule at the state Capitol, where the Republican supermajority favors tax cuts and takes aim at organized labor. Read just a few pages into his book, or listen to enough speeches, and Lee’s worldview starts to come into focus. On election night, Lee previewed the themes of his second term.

“Roads, bridges, highways,” he told reporters after his acceptance speech. “Broadband. Water and sewer. Infrastructure investment and workforce development. The state with good workers will win in the future. We need to continue to invest in vocational, technical and cultural education.”

Lee thinks just as much about what a government shouldn’t do (interfere in the state’s critical health care gap, for example, or burden citizens with taxes) as what it should do (pave roads, secure utilities, host Christmas tree lightings). He has pinned the success of his first term on statistics like new jobs and business relocations. He likes to point to a few high-profile gets like Ford in West Tennessee and Oracle in Nashville. While they paint an incomplete picture of the state’s economic health, jobs and business investment are quick talking points to voters and easily quotable.

Capitalism with few regulations, as well as a clear and public desire to reproduce the Christian upbringing he remembers fondly from growing up in then-rural Williamson County, can be understood as the two most important ideologies that will guide the governor through 2026.

Gov. Bill Lee prays with Andrew Towle

Protective of the carefully crafted image that carried him through a bitter 2018 gubernatorial primary, Lee made it a habit to avoid situations that could leave him politically vulnerable during his first term. He has courted friendly media and kept critics at arm’s length, preferring to speak in platitudes befitting a high-minded Tennessee cattle rancher — the image from which Lee has fashioned a political identity.

“I can vehemently disagree with you and still treat you with dignity and respect,” Lee told conservative commentator Ben Shapiro last month in a rare far-ranging interview. Shapiro’s company, the Daily Wire, moved from Los Angeles to Nashville last year. “I’m not the expert on civility, I just like thinking about it a lot. And I think our world could use a lot more of it.”

His praise for civil discourse has not meant a tenure defined by trade-offs or tolerance. In a state of nearly 7 million — roughly 1.1 million of whom voted for him — Lee has held uncompromising positions on the country’s most nuanced and controversial topics. Last year, he formalized the state’s so-called “constitutional carry” legislation, allowing Tennesseans to carry handguns without a permit. Despite a spate of mass shootings in Tennessee and around the country, Lee ran on loosening gun restrictions. In his book, he traces his stance on the Second Amendment to memories of his family’s gun cabinet, “full of firearms of all kinds.” After the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision rolled back protections for abortion in June, Tennessee was among the first states to institute laws restricting reproductive health care, a move long supported by Lee. He hailed Tennessee’s swift response as guaranteeing the “maximum possible protection for pre-born children.”

Leading Republican lawmakers Jack Johnson and William Lamberth have already debuted controversial bills ahead of the 2023 legislative session focused on gender identity, a topic that has become central to GOP cultural politics. The first, Senate Bill 1, would prohibit certain gender-related health care, a legal counterpart to recent attacks on Vanderbilt University Medical Center from conservative media. Another, Senate Bill 3, would add legal restrictions around “adult cabaret performances,” an apparent response to conservative outrage over drag performances. In his Shapiro interview, Lee expressed explicit support: “It’s sad, mostly, for me. As a dad, as a grandfather. Someone who watches kids navigate the hard years of 12, 13, 14, 15. It’s really sad to me that these life-altering decisions, by adults making the decision on behalf of the child. … I think you’ll see it clearly addressed legislatively in this state.”

Like other conservative lawmakers facing uncompetitive elections this fall, Lee gained a reputation for turning down requests from local media. As recently as 2019, it was common practice for the governor’s office to grant end-of-year interviews with local and regional journalists. Jade Byers, Lee’s press secretary, turned down the Scene’s interview requests, offering press releases and videos instead.

Lee’s first term focused on attracting business investment and remaking the state’s education system, punctuated by a few failed efforts at reforming the state’s carceral system. His common folksy refrain since 2018 has been that Tennesseans want a good job, good schools and safe neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the state has suffered from anemic public services, which Lee dismisses as not within the purview of government. While school districts struggle with enrollment and testing, Lee’s answer has been to stratify the public education system in the name of school choice, carving out space for charter networks to compete against traditional public schools for enrollment (and therefore funding) while tax dollars subsidize private school students. The result has been a state increasingly segregated by wealth and a growing urban-rural divide.

Lee often uses anecdotal evidence to explain complex issues. He rarely brings up charter schools’ potential to change education without referencing his own experience mentoring a student in the “inner city” who benefited from a move to charter education. When talking about criminal justice, Lee cites his experience with Men of Valor, an evangelical Christian nonprofit where he was a board member. Early in his book, Lee marvels at the story of Mr. Linton, the patriarch of a neighboring farm who lived humbly and died with a million dollars in assets. The anecdote extends Lee’s advice to those seeking wealth: work hard and practice frugality. A simpler and perhaps more obvious explanation, of course, is to own large amounts of desirable land.

While pockets of the state reap the benefits of corporate investment and real estate booms, economic growth has affected Tennesseans unevenly. There is no better example than Williamson County. Lee was raised on a few hundred acres just off the Natchez Trace Parkway and still maintains a home on his family’s sprawling property, where he also raised his children. He cites his childhood experiences as particularly formative. His estate is also home to Triple L Ranch, a joint venture between Lee and his siblings that includes horse boarding and cattle farming.

Triple L Ranch

A working Tennessee farm provides a compelling political backdrop and secures the distribution and transfer of wealth across generations, but Lee Company has always been the family’s economic engine. Lee went to work at the family business fresh off an engineering degree from Auburn in the early 1980s, eventually becoming the company’s chief executive — like his father before him and his grandfather before him.

Williamson County has grown into a shining example of the benefits of social spending — somewhat ironic, given the austerity politics of many of its highest-profile residents. It’s Tennessee’s wealthiest and healthiest county. Its per capita income leads Tennessee at $95,000 — $23,000 ahead of Davidson, the second-wealthiest, and $40,000 ahead of Wilson, the third-wealthiest. It’s home to three of the state’s top (non-charter) public schools, a sprawling network of parks (currently focused on expanding mountain biking trails), and a robust public library system. Franklin and Brentwood are national bases for Republican fundraising and influence, home to senior U.S. Sen. Marsha Blackburn, former House Speaker Glen Casada and current Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson. Junior U.S. Sen. Bill Hagerty grew up in Williamson County and lives just across the Davidson County border in Belle Meade.

The rest of the state, meanwhile, has among the worst measures of public health and education while boasting some of the highest rates of income inequality and incarceration in the country. Nearly 10 percent of Tennesseans do not have health insurance, a statistic that coincides with elevated rates of debt in the state. State lawmakers have refused to expand Medicaid, and Tennessee’s rural health care system continues a slow march toward collapse.

Lee publicly disregarded much of the guidance from the CDC and White House about COVID, adopting the laissez-faire attitude that informs his broader view of economics and political philosophy. Across the country, governments stepped forward to manage the most acute health crisis experienced by the general population in a century. Lee stepped back. At different points since the beginning of the pandemic, Tennessee has led the nation as a COVID hotspot. Lee earned a censure from Congress’ Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis and the White House Coronavirus Task Force in July 2020.

“I am a person who says, ‘People oughta decide for themselves,’ ” Lee told Shapiro in November. “If you don’t want to get COVID, don’t go out, but it’s not because I’m going to make you stay in. I decided we can trust Tennesseans. I don’t know best, the medical community doesn’t know best, they know best for themselves. I have that philosophy about children, education, health care — people know best for themselves and should be given the freedom to make those decisions.”

People close to Lee praise his instincts, calling him a quick study with the ability to paint the big picture and delegate the details. He isn’t prone to micromanagement and surrounds himself with people he trusts to implement his vision of government.

Penny Schwinn, a rising star who came to Tennessee via Texas early in Lee’s first term, is his commissioner of education. Stuart McWhorter, a prominent Nashville businessman who recently succeeded Bob Rolfe atop the Department of Economic and Community Development, is responsible for business recruitment. Butch Eley runs the Tennessee Department of Transportation, a role likely to expand in political significance with the governor’s new spotlight on roads, bridges and utilities. Jim Bryson is Lee’s finance and administration commissioner and his right hand at budget hearings this month. Brandon Gibson, formerly of the Tennessee Court of Appeals, is Lee’s chief operating officer, and Joseph Williams parlayed a failed campaign for state representative in 2018 into a position as Lee’s chief of staff. Blake Harris, Williams’ predecessor, continues to be an important adviser to the governor. Some close to Lee have referred to this inner circle — particularly McWhorter and Eley, two successful Nashville businessmen — as moderating forces against some of Lee’s more hard-line instincts.

Two major Lee policies are hitting K-12 education in Tennessee: the Education Savings Account program, known colloquially as school vouchers, and the Tennessee Investment in Student Achievement (TISA), a refigured funding formula for school districts.

Lee has also helped charter networks gain a foothold in local districts, establishing a state-controlled charter commission to handle appeals when networks are rejected by local school districts and, at this year’s state of the state address, announcing a charter partnership with Hillsdale College, a small Christian school in Michigan affiliated with the American Classical Education charter network. The alliance came with little context, and months after the announcement, Hillsdale president Larry Arnn openly degraded teachers in an appearance alongside Lee. After much ado, the network withdrew its Tennessee charter applications this fall.

Vouchers passed in 2019 amid backroom politics, with then-Speaker Glen Casada allegedly orchestrating a bribe in an effort to secure the necessary votes. After a slog through Tennessee courts, which initially blocked voucher rollout, the policy — tuition reimbursements for qualifying students to enroll in private schools — is moving forward. Schwinn quarterbacked TISA last year, significantly changing how money is allocated across districts. It updates the state’s 30-year-old resource-based funding plan with a baseline amount per pupil and additional funding weights like unique learning needs and English proficiency. Economic disadvantage, a metric that tries to approximate a student’s financial hardship, is the formula’s biggest weight.

Next to education, economic development has been Lee’s most visible focus. If you want to know what the governor will bring up at any given media availability opportunity, check the press page of TNECD for a recent press release. Business relocations — Kewpie Mayo, LG, Hitachi in recent weeks — are favorite topics whenever he’s at a mic. Each comes with quick stats on jobs created and a bottom-line investment number. On Election Day, Lee chalked a second win when voters agreed to add a right-to-work provision to the state constitution. Lee Company is the largest non-union mechanical contractor in the state, and the governor used his perch to advocate for the amendment. His official statement told voters that a “No” vote would force workers to join unions and pay union dues, a misrepresentation of the vote that drew the ire of unions and labor advocates — Lee ultimately distanced himself from the misleading statement, telling the Associated Press, “I didn’t make that tweet.”

“It’s been part of his agenda since he took office to enshrine a policy that has statistically showed higher death rates, lower wages, poorer working conditions, and no voice for workers on the job,” says David Rutledge, an organizer with Laborers’ International Union of North America. “He’s taken his business practices and extended them to the state.”

It’s a natural leap that Lee would stitch the two primary focuses of his first term — education and economic development — into the fabric of his second term. Lee has added workforce development to his stump speech post-reelection, an umbrella term that will translate to vocational and technical training throughout Tennessee’s secondary and post-secondary schools.

“We have to be that state that has the workers,” Lee told Shapiro a week before he gave an almost identical answer to reporters after his reelection. “The state with the workers will win. These are not sexy things. But they’re things the government ought to be about.” Per Lee’s ideology, owners, bosses and managers should be courted as job creators and attracted with a well-trained and pliable workforce.

The second policy area, Tennessee infrastructure, encompasses all of the state’s hardscape, like roads and bridges, as well as popular modernizing initiatives like rural broadband. With Commissioner Eley in the TDOT driver’s seat, Lee is already playing up his background in engineering and HVAC to make a point about the state’s bones. In a statement to the Scene, Eley previewed TDOT’s role in Lee’s plans to address the state’s project backlog, and he specifically mentioned traffic congestion as a stumbling block for Tennesseans. Significant cracks in the I-40 bridge from Memphis to Arkansas over the Mississippi led to a brief shutdown in 2021, a black eye for Lee and a jarring message to Tennesseans about the state of their state. With the right political coalition and a chunk of federal funding, regional mass transportation may be a rare policy area with common ground for Lee and Democrats.

Grace Chapel

Lee was nowhere to be found at the 9 a.m. service at Grace Chapel on a recent Sunday morning. Lee still publicly identifies with Grace Chapel, though the affluent megachurch just outside the Franklin town center has weathered its share of high-profile controversies. Grace Chapel founder and former senior pastor Steve Berger very publicly supported and attended the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. In summer 2021, the church became a flashpoint for allegations of sexual abuse and murder aimed at former WSMV anchor Aaron Solomon, a member of the congregation, by his daughter Gracie. Berger stood behind Solomon before resigning in August of that year.

Grace Chapel epitomizes the nondenominational “Charismatic Christianity” that took root in America in the late 1990s and has risen in popularity behind rock-star preachers, casual dress codes and high-production pop hymns. Sunday mornings feel like concerts, and sermons stray quickly from scripture. Nov. 20’s sermon turned the story of Cain and Abel into a parable about the virtues of giving money to the church.

Faith is Lee’s most comfortable terrain and an easy way to tie his policy decisions to expressions of morality. He explains his life as repeated triumphs of hope in the face of hardships — losing his first wife to a tragic accident, his second wife Maria’s recent lymphoma diagnosis. God has rewarded his humility and faith with blessings, like material wealth and a high political office. As evidenced by his stances on abortion or economic inequality or health care, Lee arrives at his moral truths via secular filters — supply-side capitalism, the supremacy of markets, a patriarchal attitude toward decisions about pregnancy.

This year, Lee serves as the vice chair of the Republican Governors Association. It’s a potential stepping stone for higher office and historically a Tennessee mantle. Bill Haslam, Lee’s predecessor, chaired in 2014 and 2017. Ahead of the next presidential cycle, poles are forming in the GOP around former President Donald Trump and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis — both angry, both indignant, both ready to sling mud in a protracted primary. Lee has comparable hardcore conservative bona fides, but he doesn’t talk about California liberals or Northeast elites. Presidential ambitions would likely have him sizing up the same benevolent Christian lane he took en route to his Republican primary upset back in 2018. Reaching for the national spotlight would also cut against his carefully maintained image as Tennessee’s agrarian servant, humbled by God and wary of power. Sources familiar with Lee believe he’s more focused on completing projects in his second term that would cement a legacy in Tennessee political history. Then, with credibility intact, he could return to his C-suite and plow.

Ahead of his fifth legislative year, Lee has built second-term priorities off first-term momentum. He wants to finish education funding reforms, continue to support charters and subsidize private school students. Lee has set up a turn away from traditional public schools in the name of providing families with choices, re-creating an education ecosystem that more closely mimics market dynamics. Tennessee has attracted corporate investment and seen significant population growth since the last census, but economic measures reflect a profoundly unequal state, particularly as the governor maintains a legal environment hostile to organized labor. Workforce development and infrastructure will be themes through 2026, both serving Lee’s apparent view that government mainly exists to serve business interests.

Lacking power, money, party structure, organization and effective messaging, Democrats have failed to win a statewide race since Gov. Phil Bredesen won a second term 16 years ago. For four more years, it’s Bill Lee’s state.

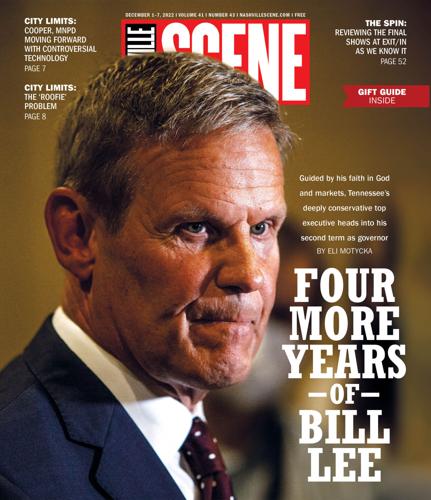

Gov. Bill Lee