Edward Ratcliff. Rank and organization: First Sergeant, Company C, 38th U.S. Colored Troops. Place and date: At Chapins Farm, Va., 29 September 1864. Entered service at: ------. Birth: James County, Va. Date of issue: 6 April 1865. Citation. Commanded and gallantly led his company after the commanding officer had been killed; was the first enlisted man to enter the enemy’s works.

The Battle of New Market Heights and Chaffin’s Farm, as it is now known, was a critical victory for the Union during the Siege of Petersburg. It doesn’t have the broad cachet of the better-known Civil War battles at Gettysburg or Antietam or Fredericksburg, but the victory forced Robert E. Lee to redeploy his troops, sending the siege into the grind of trench warfare for the remainder of the rebellion.

That’s what a military historian would tell you about New Market Heights. But Bill Radcliffe will tell you differently.

“It’s hallowed ground,” he says, tears welling up in his strong eyes as he looks around Fort Negley on a crisp and bright February morning. “Just like here.”

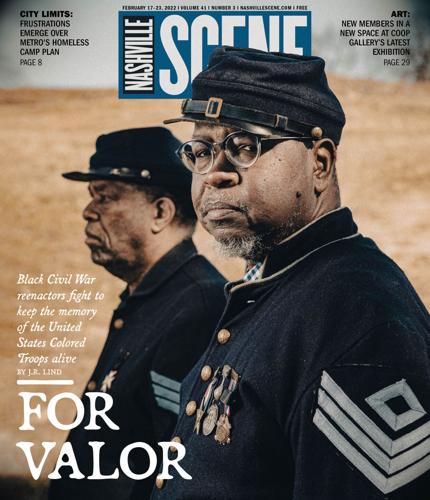

Radcliffe is a United States Colored Troops reenactor with the Nashville-based 13th Regiment of the United States Colored Troops Living History Association. He’s wearing the uniform of the USCT: dark-blue wool, the rank insignia in lighter blue on the sleeves and a matching cap. There’s one award on his uniform, indicating he’s a direct descendant of a Medal of Honor winner.

Edward Ratcliff quite literally fought for his freedom, spilling his blood for a country who said he was three-fifths of a person. Bill Radcliffe, his veins coursing with Ratcliff’s blood, is making sure no one ever forgets.

The story of the USCT was a footnote for too long in American history, the contributions of its soldiers — sometimes just weeks removed from enslavement — consigned to passing mentions in textbooks. Twenty-thousand Tennesseans joined the USCT, the second-most of any state after Virginia. Fifteen USCT soldiers, including Ratcliff, won the Medal of Honor — 14 of them at Chaffin’s Farm and New Market Heights. (Another three Black soldiers also won the award while attached to other units; eight Black Civil War sailors won it as well.) Records show that white officers recommended commissions for many of the Black soldiers after their valorous bravery at the battle. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ignored them all.

Though President Abraham Lincoln had been authorized to enlist formerly enslaved people since 1862, it wasn’t until General Order 143 was issued by the War Department in May 1863 that the USCT came into being.

Lincoln was concerned about the Union’s tenuous hold on four border states and the political fallout and effect on public opinion that arming Black men would have.

“The Great Emancipator?” Radcliffe says, raising a suspicious eyebrow. “The Great Politician, that’s what he was.”

Lincoln’s generals, however, were facing a manpower problem. The Civil War was bloody and brutal, and as the Union began to take control of more territory, the lines were getting thinner. At first, the USCT regiments were used for tasks like guarding arms depots and rail lines, at the rear of the fighting. Eventually, Radcliffe notes, “All the white boys were dying.” And so the USCT went to the front.

They were often given the most dangerous combat assignments — more than half of the Black soldiers fighting at New Market Heights were killed in action, for example.

“All through history, we’ll wear the uniform and they’ll spill our blood, but we’re still second-class citizens,” Radcliffe says.

Official integration of the military wouldn’t come until President Harry S. Truman issued an executive order in 1948. (Functional integration, especially in the Navy, had existed since the Revolutionary War.) By that time, generations of Radcliffe’s family had worn the uniform. He himself served in the Navy during Vietnam (“the Southeast Asian Conference,” he jokes), extending a family tradition that spanned two world wars and stretched back to a man once held in bondage who charged into a fort held by an army intent on keeping him there. In fact, following the Emancipation Proclamation, the Confederate government issued an order that any Black soldiers captured would be enslaved and their white officers would be executed.

Many Americans first learned of the USCT via the 1989 film Glory, based on the true story of the all-Black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (which, it should be noted, was not a USCT unit). Gary Burke, another USCT reenactor, had his interest piqued by the film. After all, nothing in his textbooks had taught him about these men who took up arms for their own freedom. Insofar as history teaches students about Black Americans during the Civil War era, it’s often focused on rhetorical heroes, like Frederick Douglass or Sojourner Truth, or the Underground Railroad, even glossing over the fact that the Railroad’s most famous conductor, Harriet Tubman, served as an armed scout for the Union Army.

Nor do the texts mention that Douglass was an ardent supporter of Black men joining the military.

“An eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and his bullets in his pockets,” Douglass once said, “there is no power on earth … which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.” It’s one of Burke’s favorite quotes, and one he can recite the same way schoolchildren can recite the Pledge of Allegiance or a catechumen can recite the Apostles’ Creed.

Douglass was a great believer that true citizens could not be denied “the ballot box, the jury box and the cartridge box,” and that fighting shoulder to shoulder — at least metaphorically — with their white fellows would serve as proof that Black Americans were Americans in the full sense. “Is he not a man?” Douglass wrote in his newspaper Douglass’ Monthly. “Can he not wield a sword, fire a gun, march and countermarch, and obey others like any other?”

But, of course, it wasn’t that simple.

“The advance of Black people,” Burke says, “threatened white society.”

Burke’s great-great-grandfather Peter Bailey joined the USCT’s 17th Regiment when he was 18 years old, traveling from Lebanon to Murfreesboro to do so. He was 5-foot-4 — one of those tiny facts from history that hits home. Barely an adult in age, he must have looked like a child in his uniform.

Battle of Nashville historical marker

But he was garrisoned at Fort Negley and fought in the Battle of Nashville on Peach Orchard Hill and at Granbury’s Lunette. The latter, on Polk Avenue near Murfreesboro Road, is now honored with a historical marker — as it should have been for decades — because that’s the first place where the USCT actually fought Confederate soldiers.

Attached to Gen. James Steedman’s division, eight USCT regiments were tasked with taking the lunette. It was costly. They suffered heavy losses and failed to take the small fortification.

Ultimately, of course, the Union won the Battle of Nashville, virtually securing the Western Theater for the U.S. But the combination of that action and what was accomplished by the construction of Fort Negley makes Nashville hallowed ground.

Fort Negley was the largest inland fort built during the Civil War and was constructed in large part by former slaves who fled to the Union lines, and freed Blacks conscripted out of Nashville’s churches. After the war, white Nashville mostly ignored it. It was, after all, a Union fort. And Nashville was, after all, a catastrophic and embarrassing defeat for the Confederacy. And after all, it was a place of pride for Black Nashvillians, many of whom settled nearby after the war.

But Black Nashville never forgot — even as it was overgrown, eventually ruined and abandoned — until its restoration during the New Deal. And Bill Radcliffe never forgot.

In 1989, dressed in his period uniform, he took “a milk crate and a blanket” and sat on the balustrade on the anniversary of the Battle of Nashville in December.

“I did it out of respect,” he says. “I didn’t want it to be forgotten. I was reenacting with other men. I traveled and connected with my brothers on the East Coast, and I knew what happened here. It was my way of honoring the soldiers and civilians that built this place.”

So Radcliffe sat. He’d answer questions and tell the story of how Fort Negley came to represent the promise of freedom, the promise of full citizenship. But it was more personal. He said coming to the fort, he had a “spiritual moment.”

“I said my prayers for them. I reflected on what it was all about.”

“Most [Black] people in Nashville are descendants,” says Radcliffe. “People I go to church with are direct descendants. But people in this town tried to just sweep it under the rug.”

Or under concrete and pavement. The future of Fort Negley was threatened in 2018 as part of a high-profile redevelopment project proposed after the Nashville Sounds left neighboring Greer Stadium for what is now First Horizon Park. The project kept creeping forward over the objections of historians and a diverse group of activists, including the NAACP and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Eventually, after archaeologists found evidence of burials, the project was shelved.

Black Nashvillians insisted throughout the process that they knew there were burials there — of soldiers who were garrisoned there, of civilians who helped build it. They’d heard the stories from their grandparents. It was a known fact in the Black community for more than a century, if only white Nashville would listen.

Radcliffe doesn’t like to talk too much about what he’s accomplished.

He was an extra in Glory, for example, but asking him about it just gets a nod. He was the model for the statue honoring the USCT soldiers buried at the Nashville National Cemetery on Gallatin Pike (it’s the only statue there), but he makes Burke tell that story.

“I guess I got my 15 minutes or so,” Radcliffe says.

“I wonder sometimes if we’re doing any good,” he muses aloud.

He says so often people want to “deny or denigrate” the service of Black Civil War soldiers.

Reenactment is more than running around on battlefields, camping out like they did 150 years ago. Reenactors do educational events and commemorations. At one such event, Radcliffe heard a boy — maybe 8 years old — tell his sisters who were approaching his table say, “Oh that’s stupid stuff — it’s not important.” Radcliffe says it made his blood boil. Someone, after all, had to teach the child that the contributions of the USCT were somehow less-than.

But that also means someone can teach the child — and others — that they weren’t.

Yes, the heroism of the USCT — and the Black service members who came after them — went unrecognized. Men who fought for their country went home after Appomattox to find their lot in life little better than it was when they were enslaved. Full access to the ballot box and the jury box was a century away.

“History tells on itself,” Radcliffe says, recounting the generations of fighting men who spilled blood and won medals doing so, “fighting for democracy,” returning home only to be forced to the back of the bus, to be beaten blind by racist police for daring to assert their humanity.

“This nation always has to fight itself on what’s right and wrong,” he says.

And yet, again and again, all the way back to the USCT, Black Americans joined the fight.

“Because we always have to prove ourselves,” Radcliffe says. “It’s sad to think my grandchildren will have to be strong and face it too.”

“But it’s going to be OK,” he says after he reflects for a moment. “What we [as reenactors] do may seem like a drop in the bucket, but somebody will come along. … And they’re asking questions, so we’re still trying. Sometimes we paddle upstream.”

Burke and Radcliffe agree that the younger generations are better informed about Black history in general and about Black military history specifically, because more has been written, and information is just easier to get.

“We do worry about the next generation, but seeing it up close, it has them wondering and reading,” Radcliffe says. “Kids now are a lot more informed.”

Civil War reenactment in general is on the decline from its peak in the 1990s and early 2000s. It’s an expensive avocation, for one thing. There’s lots of travel, and period reproductions don’t come cheaply. It’s been harmed by the general trend against “joining” that’s concomitant with the rise of social media — the same phenomenon that’s lowered participation in all number of veterans’ groups, bowling leagues and civic organizations.

And there were never a lot of Black reenactors to begin with. There are two groups in Tennessee — the 13th in Nashville and another near Chattanooga. Burke notes that USCT reenactors are a lot more common in the North.

But that’s not discouraging to Burke and Radcliffe. It’s a calling. They are maintaining the memory and the honor of the men who wore the uniform. The soldiers of the USCT were not metaphorical freedom fighters. They were literal freedom fighters — literally carrying a rifle and putting themselves in the line of fire for the promise America doesn’t always live up to. They shouldn’t be forgotten or footnoted, and as long as Burke, Radcliffe and others like them are around, they won’t be again.

Here on this crisp and bright February morning, Radcliffe looks up at Fort Negley. The tears are welling up again as he motions toward the slopes.

“This is for those people who were up there.”

Bill Radcliffe (left) and Gary Burke at Fort Negley