Some of the REACH team, from left: Kelsey Taylor, Kiara Haynes, Michael Randolph, Capt. Jerry Pradines, Capt. Chad Walker

It wasn’t long ago that advocates were still calling for a non-police response option, amplified in November 2022 by a Metro Nashville Police Department officer shooting and killing an unhoused man who experienced mental illness.

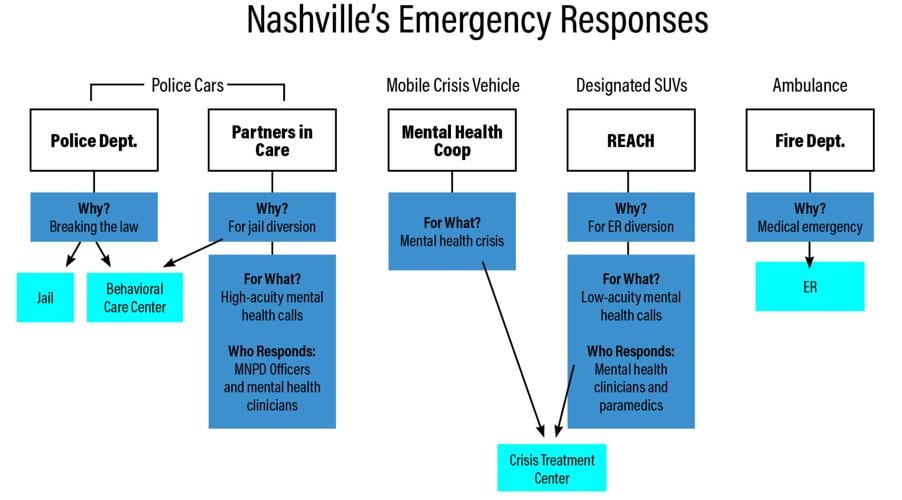

In February, that option appeared. Responders Engaged and Committed to Help (REACH) launched, pairing paramedics from the Nashville Fire Department and mental health professionals with the Mental Health Coop to respond to low-acuity crisis calls received by 911.

At a Thursday Behavioral Health and Wellness Advisory Council meeting, the Metro Public Health Department presented data compiled from the first seven months of the REACH program (Feb. 13 through Sept. 30), plus an update on the city’s Partners in Care program, which launched in 2021.

Partners in Care pairs mental health clinicians from the Mental Health Coop and police officers with MNPD. After adding the program at the Midtown Hills Police Precinct in April, Partners in Care is slated to be included at all city precincts in May 2024 — adding the East Police Precinct in March and the West Police Precinct in May. The program also hired a follow-up coordinator in December. From July 1 to Sept. 30, 5.8 percent of calls resulted in an arrest.

REACH has a small team of two paramedics and two mental health professionals, and operates Tuesday through Friday 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. The pilot program is set to run until June.

In its tenure, REACH professionals have increased their responsibilities. In August, they began to take individuals directly to the emergency room instead of calling an ambulance. REACH also stopped sending cautionary fire trucks with every call by the end of the first six months.

REACH responded to 355 calls in its first six months, averaging 10 to 15 per week. The most commonly served ZIP code was 37203, near downtown. The next-highest was 37013, in Antioch — consistent with first-quarter results.

The program is meant to help people get access to mental health care, but also to take pressure off emergency rooms and ambulances in the city. Forty percent of them ended up at the emergency room anyway. That number is down from 49 percent in the program’s first two months, but up from a low of 32 percent in April. In addition, 25 percent were transported to Mental Health Coop’s Crisis Treatment Center; 18 percent were provided resources or referrals; and 8 percent were transported to another inpatient center.

Calls skewed male (54 percent) and young (23 percent between the ages of 25 and 34). Sixty-three percent were white, 30 percent Black and 7 percent another race. They also skewed low-income, with 36 percent unhoused or in temporary housing and 57 percent on Medicaid or Medicare.

The 911 operators and dispatchers are crystallizing their list of questions for Partners in Care and REACH, emergency communications director Stephen Martini tells the Scene.

“We’re not solely measuring the success of these programs by looking at, ‘What didn’t we send?’” he says. “We’re also looking to say, ‘Did we send the right resource to help the person in need? Were they truly experiencing a mental health crisis or a mental health concern, and did they need to be connected to mental health resources?’”

Overall, 72 percent of the calls REACH responded to required a crisis assessment. Michael Randolph, manager of the co-response programs with the Mental Health Coop, said the level of need was higher, and more serious than he anticipated. Seventy-two percent of REACH calls involved people experiencing suicidal ideation, 25 percent experiencing psychosis, and 4 percent experiencing homicidal ideation.

“All of the REACH calls would have ended with an ambulance transporting them to an ER, so we’re trying to streamline the care in a great way with some of these really high-intensity calls,” Randolph says. “That’s really good. We’re saving an ambulance bill and ER bill and, like, saving a person from having to tell the story a bunch.”

Michael Randolph

Mental health beds are scarce in Nashville, but that hasn’t been a huge issue, Randolph says. Stays at the Crisis Treatment Center are short, usually around 24 hours to stabilize people and connect them to resources before transporting them home or to another treatment center.

Randolph says his team is working to develop partnerships with area hospitals and drug treatment facilities to avoid long wait times for patients.

“It is really hard to get someone into a location quickly,” he says. “We’ve been trying really hard to develop those partnerships and really advocate for the people we see.”

Dia Cirillo, former senior policy adviser under Mayor John Cooper’s administration, led initial conversations about Partners in Care through Metro’s policing policy commission. She said the city’s co-response is a direct result of a demand for new services that followed the murder of George Floyd.

“That happened in 2020, and we developed those new services, rolled them out, and those services are now meeting their original charge,” says Cirillo. “We’re developing a tool kit that never existed before. We’ve learned ‘tough on crime’ doesn’t work.”