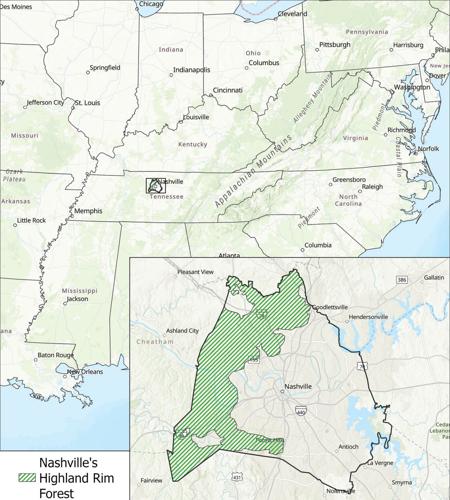

The stretch of tree canopy that lines the western border of Nashville is now considered by some local environmentalists to be the world’s largest urban forest within the limits of a major city.

One Nashville-area group is trying to increase protections for that section of trees — a part of the Western Highland Rim Forest — while also working with Metro and the state to provide additional tourism destinations apart from downtown’s honky-tonks. The Alliance to Conserve Nashville’s Highland Rim Forest recently secured a Wikipedia article for the geological area and hopes designating the forest as the largest within the city limits of an urban center will bring more awareness to the area.

Judson Newbern, lead volunteer of the alliance, recently caught up with the Scene on the current state of the group’s efforts.

On Working With Metro

“Metro has pressure to develop, and the Planning Department asked us if we would focus looking at that northwestern corner of the county that is Joelton and Whites Creek, because that’s the cleanest water, cleanest air, and it has the most risk of creating stormwater damage if you start paving those surfaces that are now under trees and soaking up water. You get more runoff, and you could get something like Asheville [floods] happening.

“Slopes are what our concern is, because Nashville does not have any protection on developing slopes. This gets into the delicate subject of the Republican agenda of letting people have any rights to their land and with no constraints. We’re not trying to simply go to an extreme, and we understand development needs to take trees, but to do it in places that are not as environmentally or ecologically diverse or as vulnerable as some of these slopes are.”

Radnor Lake would be considered part of the Western Highland Rim Forest

On Development

“Part of this is putting something in place that simply says to businesses, ‘We’re very much on board with supporting mass transit, putting density along corridors where there is development and working toward affordable housing, but in places where you do have level land that makes sense to invest.’

“Not [to] feel like it’s alienating development, because it’s not. It’s just simply trying to, in a controlled way, figure out where is the best spot. It’s where you already have the septic lines and the utilities to be supportive rather than going into a new area that ends up getting chopped up.”

Amid the city’s development boom, advocates try to conserve the mature tree canopy

On Conservation Easements

“What we’re trying to do is to get the average citizen who appreciates that they’d love to see the hill, they like the ridge lines unblemished, that if they don’t start thinking about that, it will become fragmented like some of the other cities. As you start breaking down into clearings, the natural habitat is reduced. What we want to do is get people who own these slopes to think about putting what are called conservation easements on the slope. The owner continues owning it, but it makes it so that they can put whatever limit they want. You have nonprofits that have to make sure that the easements are honored in the long term, because if someone sells the land, that easement goes with it. These nonprofits that do the long-term holding of the easement are obligated to inspect the property once a year to make sure nobody put a trailer on it or nothing has gone on that was not covered in the easement.”

On Ecotourism

“We thought about, maybe along the ridge line, you could get easement put in and put trails in that could be part of the Highland Rim — just like the Cumberland Trail [in East Tennessee] — and you could start connecting these parks within Davidson. But then go to Williamson County and do an entire hike with bed-and-breakfasts and all these things that would be really great for a city of this size, and it’s really kind of an unusual opportunity.”