How do you get an entire city to make an artistic statement about the way it sees itself? One that doesn't weigh celebrity over average citizens, or technical proficiency over untrained visions and unusual viewpoints?

The answer's in a remarkable new project at the downtown Nashville Public Library: one hand-printed selfie at a time.

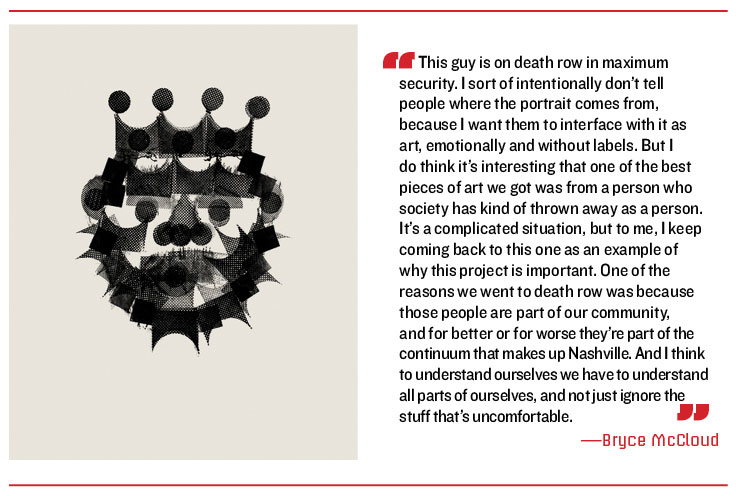

"It's an interesting way for you to introduce yourself to another person," Bryce McCloud says. "With a photograph, you're kind of stuck with whatever you look like. But I feel like a self-portrait can really be anything. It can be more about who you are inside, or some part of you that people can't see just by looking at you."

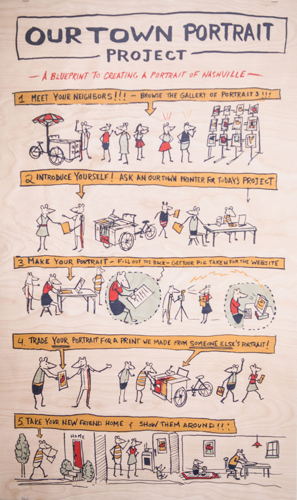

That was the seed that created Our Town, the large-scale citywide art project McCloud embarked upon last year with a changing cast of printmakers, photographers and assistants. The idea was simple: Ask people to make a self-portrait, and give them one in return.

Part of the Our Town exhibit at the Downtown Library

Distilled for the moment into an exhibit called Our Town Nashville: Field Reports, the result has transformed the library's second-story atrium into a dizzying assemblage — a kaleidoscope of hundreds of faces that's as dazzling from a distance as it is engrossing in each solitary portrait.

"We're thinking of this exhibit as halftime, like an intermission," McCloud says upstairs, radiating Willy-Wonka-in-the-chocolate-factory waves of excitement. But to look at the exhibition that's currently filling all four walls of the library's second level, overlooking its main floor with prints, videos, maps and photographs — you wouldn't consider it halfway through anything. It's extensive, elaborate and about as ambitious as public art projects get.

But for McCloud, a lifelong Nashvillian, it's just the beginning.

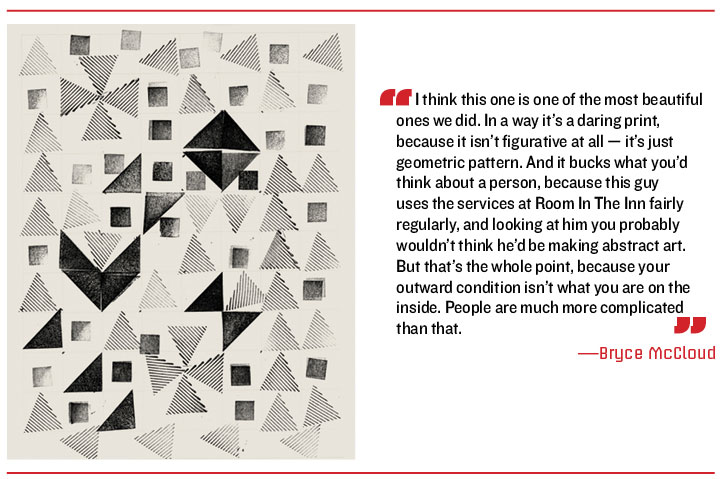

The project started at Room In The Inn two years ago, when McCloud was the artist in residence. As part of its efforts to help homeless Nashvillians reclaim their lives, he led weekly art-making classes and brought in experts in multiple media. For one class, students tore pages out of recycled magazines and painted warm wax over them. McCloud's only condition for the classes was that he be able to keep the work that was made, which he promised he would turn into a conversation with the entire city.

That was one of the earliest incarnations of Our Town, which has always been about self-portraiture. The details came later, like the bike cart that worked as a mobile display case, and the jumpsuit each Our Town facilitator wears.

Bryce McCloud and Elizabeth Williams with some of the stamps used to make portraits

"It's required!" McCloud says, mocking his own zeal like a character in a Christopher Guest movie. He and the rest of the Our Town crew — Elizabeth Williams, Travis Bly, Griffin Norman and Josh Rowe — set out to capture self-portraits of Nashvillians they met in places as unlikely and varied as Riverbend Maximum Security Institution and the North Police Precinct, Fond Object and Parnassus Books.

"The reason we made a bike cart instead of setting up a shop at Green Hills mall," McCloud explains, "is that we wanted to go where people were. It's easy for folks like me to be mobile and see where something like this is happening. But there's a whole other part of Nashville that's immobile for whatever reason — whether they're handicapped or in jail, or can't afford it or are too busy to travel, or they're bed-bound in a nursing home."

The Our Town bike cart in action

McCloud credits the Metro Nashville Arts Commission with helping him and his team mount the project on the scale he envisioned. He approached executive director Jen Cole early on, and the commission secured him the necessary funding as part of Mayor Karl Dean's support of public art.

"It was funded through the Percent for Art," says Caroline Vincent, Metro's public art manager. "It's different from what we normally fund, which has traditionally been a sculpture. But in this case we wanted to work with a local artist. We partnered with him and funded this last year-and-a-half — the cart outings, and the collections of prints that will come out of it that will be part of the collection of the Nashville Public Library."

So far, McCloud has visited 46 places in all, and he'll probably add a few more in the spring. Eventual funding is projected to be about $100,000. But so far only 65 percent of that has been given — evidence of how much more this project has in store. By focusing on process, and ultimately placing that process in the hands of participants themselves, the project encourages citywide engagement with art — without the pretension, self-congratulation and sentimentality that often accompanies such efforts.

Making portraits at an Our Town setup

"It's really simple," he says, "but it has a lot of moving parts. It's hard to explain sometimes in a few words, but when you see it happen, it all makes sense."

The exhibit features an alcove full of material McCloud and his crew took with them throughout the yearlong project, something they refer to as "field work." There's a map of Nashville with pins in every location they visited. McCloud was adamant that the map be an old one, "because our city has a history; it didn't just arrive last year."

Even the small signage that denotes individual parts of the exhibit — like the time-lapse video of portraits being made and the short documentary about the project shot by local filmmaker Doug Lehmann — is carved into tiny wooden panels. Other panels illustrated with cartoon mice depict every step of the process. And yet the exhibit never seems precious — just fully envisioned and realized, like a public-art version of a McSweeney's publication or a cabinet of curiosities.

Still, the highlights are definitely the portraits. Culled from almost 1,200 works McCloud and his team collected over their year of traveling around Nashville, the portraits are presented in grids of black wooden frames. Other portraits are copied as two-color prints and hung from metal fasteners like clipboards.

Perhaps most striking is a wall of 32 oversized black-and-white photographs mounted on wooden boards. These are people holding the prints they'd just made. Here you'll see councilmen and police officers, Mexican muralistas and art students, each holding their self-portraits up to their chests like proud schoolchildren.

Two of these portraits are uncannily similar. One belongs to Jack White, probably the single most recognizable figure in the exhibit. The other is in much smaller hands — those of a boy participating in the Our Town project as part of Family Day at Casa Azafrán, the community center on Nolensville Road. In photographs, the two look nothing alike. And yet each holds a self-portrait with the same two circles for a nose, round semicircle lips and small squares scattering to fill the edges around the head.

"Jack's been a great supporter of both the shop and the project," says McCloud, who's worked on projects with White's Third Man Records (most notably the stunning The Rise and Fall of Paramount Records box sets, which rival Our Town for sheer obsessiveness of detail). White's portrait is one of the ones McCloud chose to turn into a print to take out on the cart, although McCloud didn't label it or tell anyone whose portrait it was. It traveled with Our Town for months without fanfare.

"The last place we went was Casa Azafrán," McCloud remembers, "and this little guy was there. His family was doing the project, but he wasn't really into it. Finally, he sat down. It can be kind of hectic when we're making these portraits in a large group, and it's hard to keep an eye on what everybody's doing. So when I came back to him, I saw that he'd copied Jack's portrait completely — even improved on it a little!"

The boy told McCloud that he'd seen the portrait on the cart and really liked it, so he'd copied it and made it his own. When McCloud explained that the portrait was actually Jack White's, the boy gave him a blank look. McCloud realized he had no idea who the rock star was.

"It's great, because he really responded to the piece because of art, not because of celebrity," McCloud says.

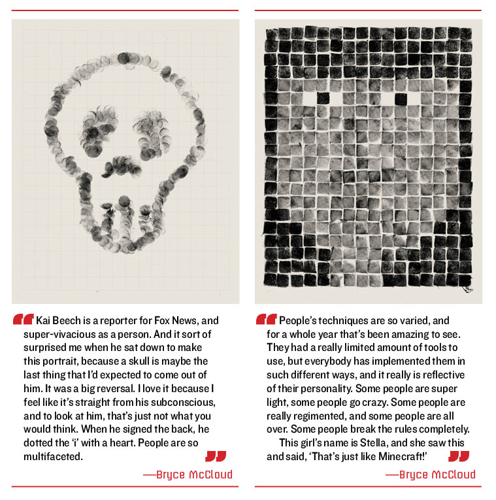

That kind of accessible creativity is important to McCloud, and it's at the heart of Our Town. Each stamp was created specifically for the project, which means no one had the sort of familiarity that might have given them an advantage. Even the portraits made by accomplished artists and illustrators — and there are several on display — were created by people unacquainted with the tiny half-moons and cross-hatched square stamps, an element that gave everyone an equal opportunity to create something special.

"Prints are a democratic form of art," he says, "because there's not an original, and kind of by the very nature of them, they're about sharing. You can make multiples, and more than one person can enjoy them. But to see your art turned into a print, I think, is a really special thing. I wanted this to edify people and make them build up self-esteem. So it doesn't matter if you're rich or poor, if one of your portraits gets made into a print and you see that out there, it makes you feel good."

What makes Our Town Nashville: Field Reports remarkable is that it doesn't just showcase the portraits, but frames them so firmly in the citywide context in which they were created. On their own, many portraits are exceptional — some are like woodcut children's book illustrations, others Bauhaus-style exercises in minimalism. Even the least interesting portraits help project a cohesive whole — each made from the same stamps and to the same scale as their neighbors — with the pattern of the library's marble tile floor reflecting them like a mirror. At its center, the exhibit is a dynamic contemplation of what community can be.

"This project is really multilayered, but one of the parts that's important, too, is that I want people to see one another for who they really are," McCloud says. "And part of seeing is about being an active looker and a careful observer. And that's what I think one of the benefits of visual art is, because when you look carefully you start to see that it's not just a group of people — it's individuals, and all of those individuals have different characteristics. And for the time that you're making a portrait with us, you have to stop thinking of other people as a group, you have to start thinking of them as individuals."

But the project is far from over.

"This is the experimental wall," McCloud says of the single mural that covers an entire wall of the exhibition space with more than 400 individual shapes printed with black ink on plain white paper. "This wall is a manifestation of the process of stamping. These are all textures that people used to stamp, but we blew them up on a giant scale, and it's sort of a test platform."

And here McCloud goes into the pitchman mode that's helped entice otherwise skeptical or reticent people — passers-by who would never consider themselves creators, or think of making art — into becoming exhibited artists in a citywide brigade.

"In 2015," McCloud says, drawing the listener closer with conspiratorial fervor, "we're going to take the things that people have made and start to reinterpret them and present them back to the city as large-scale pieces of public art. For a year, people have been making their self-portraits, but I've been watching them. My staff and I have been watching how people make portraits, and I've learned a lot. The way people combine shapes together and textures are things that I would never ever do myself before now.

"The technique has been informed by a year's worth of watching other people make these things," he says, holding his hand out into the atrium with a sweeping gesture. "It was an amazing journey to go to all these places and meet these people, and I really wish every single person in Nashville could have done that with us, but I know that they can't. So 2015 is about me as an artist trying to re-create those feelings and experiences in visual ways that I can show the community.

"Of course it's not going to change everything. But it's a little glimpse of how to think about the world."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com

Photos of Our Town in action are courtesy of Isle of Printing

After participants finish their portraits, they are photographed with them.

Bryce McCloud at the Nashville Public Library