Jason and the Scorchers

Everyone was a little bit older. Those on stage at The Factory at Franklin and those in the crowd.

It was a fun parlor game to imagine some of these men, with polo shirts tucked into their pleated khakis adorned with cellphone holsters, three decades earlier. Was their hair, now thinned, ever swept up into a mohawk? Behind the dozens of Dockers in their closets are there hidden pairs of tight turn-ups?

Whether or not that was the case, their eyes glinted behind bifocals when Jason and the Scorchers guitarist Warner Hodges kicked off the final set at Thursday's special edition of Music City Roots by spinning his Telecaster and ripping those countrified punk licks sounding, as ever, like what would have happened had The Clash's Mick Jones was born in Waverly, Tenn. instead of Wandsworth, London, England.

The show — which featured the Scorchers along with a host of Reagan-era local-rock legends — was curated by inestimable Nashville music journalist and singer-songwriter Peter Cooper, who never stopped smiling. It was a benefit for idiosyncratic Nashville treasure Tommy Womack, mobile again after suffering a devastating car wreck in June.

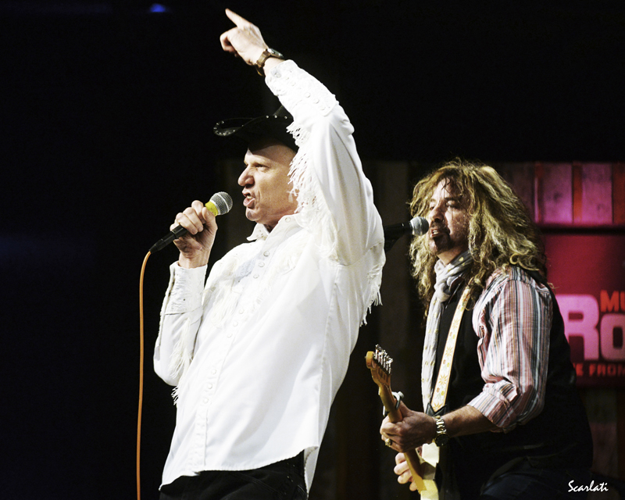

Dan Baird (left) and Warner Hodges.

This wasn't Cantrell's or Cat's; this was the Factory at Franklin, so no one crowded the stage or thrashed about. When Keith Bilbrey announced the show featuring the "greatest roots rockers of the last few decades in Nashville" would begin in five minutes, The Spin shuffled dutifully to our seats.

But any chance of this being a show of treacly nostalgia was bashed like a mailbox by a car of screaming country-punk teens in an Oldsmobile Deuce-And-A-Quarter when Dan Baird, lead singer of the Georgia Satellites and boot-stomping rocker, nodded to Hodges and launched into "Keep Your Hands To Yourself." Though the crowd was familiar with Baird's later work (including his current efforts with the band Homemade Sin, perhaps the most perfect name for a Southern rock band ever devised), he's a competent enough pro to know what the people want to hear. So that 1986 smash, a sonic redneck right cross to the mascaraed eyes of glam-metal rockers, pounded and thumped and Hodges spun and wailed, ever the consummate sideman, knowing when to back off and let the lead singer do what lead singers do, a craft honed by years standing to Jason Ringenberg's right, an enviable and often-dangerous place to work. Still wearing that unkempt mastodon hair-do, now streaked with gray, earned like the distinctive mark of a silverback gorilla, and still squeezing into those skinny jeans, Hodges is perfect in his role, taking the limelight when its time and passing it back at the ideal moment.

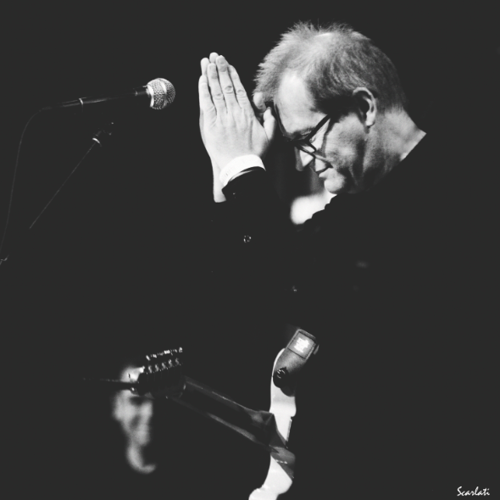

Tommy Womack

Baird wore a Mad Hatter's chapeau, like something that was discarded from the set of Tom Petty's "Don't Come Around Here No More" video, and the band rolled like the Heartbreakers at Spinal Tap volume.

Setting the table for what would be a bit of a recurring theme — perhaps these just-famous-enough rockers who still drive from gig to gig, had sharp moments of reflection after Womack's brush with death — Baird played "The Younger Face," his tribute to The Aging Rocker.

"A younger face could come and take your place," the song's A&R antagonist says. "Step aside."

There would be no stepping aside on this night. When Baird played a disconcertingly punched-up cover of Bruce Springsteen's "Johnny 99," there was no bleakness or reflection in his version of The Boss' tale of a murderer's woe. There was only id.

This was no night of half-interested legends turning out to collect a paycheck by playing by-the-numbers cutdown classics. (No paychecks were to be had in any case, as the night's proceeds, which topped $10,000, all went to help Womack defray his medical bills). This was a celebration and a middle finger to mortality and middle-of-the-road safety, to the kind of hackiness that kept these legends from achieving the kind of chart-topping success that a fairer universe would have rewarded.

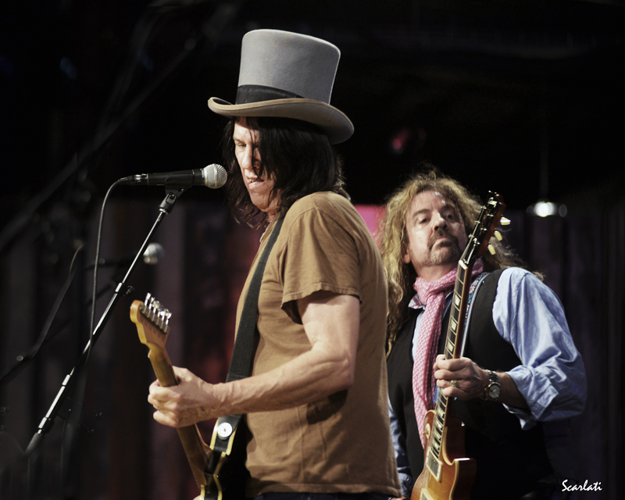

Webb Wilder

Webb Wilder, the world's most important Mississippi-born nerd, and his band The Beatnecks thumped through a repertoire of swampy, Delta blues-influenced rocky-tonkers. Truly, Wilder, still in that perfectly shaped cowboy hat and those actuary's glasses, is The Last of the Full-Grown Men, confident enough in his badassery that if some marketing-guru beardo millennial tried to tell him when to wear flip-flops, he'd chuck a full can of Dixie at his ironic smirk.

Alabama guitar legend Will Kimbrough — a bar-band legend across SEC country, once so beloved that marquees in his home state would advertise him simply as "Will" — hopped up next, his casual style incongruous with the extraterrestrial things he could make his ax do. Womack joined him — they play together as the combo Daddy — in a triumphant snub to Luke 4:24. This prophet is beloved in his hometown and all of Womack's bizarre, honest, hysterical, touching, outré observations were lapped up by the loving disciples. Preaching to the converted? Perhaps he was, but souls soar at the sound of a stirring sermon and Nashville has produced few tours-de-force as epic as Womack's eight-minute reflection "Alpha Male and the Canine Mystery Blood," a stream-of-consciousness opus that's more oration than song, this city's analogue to A Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man, a tale of Nashville wonder and woe that could make both Dylan and Peter Taylor bow in admiration.

"There's many times I came and went," Womack sang, the appropriateness of the line striking him almost suddenly.

During one of the commercial breaks for the show's radio broadcast, Marshall Chapman sang an anthem equally rock-ribbed feminist as Cecile Richards' congressional testimony and vulnerable as a soft-focused leading lady in a rom-com, while Bill Lloyd showed what it would look like if Burl Ives somehow wrote as catchy a power-pop song as Big Star ever produced.

Marshall Chapman

And no night of pre-It City Nashville triumphalism would be complete without Jason and the Scorchers, coming on last like the Household Cavalry at the Queen's Birthday. The progenitors of cowpunk, who've taught generations of us that there's nothing wrong with wanting Dead Kennedys to cover Charlie Rich and that our vowel-abusing accent is no barrier to screaming "Bullet." Like a city where a strip club is within sight of the Southern Baptist Convention, the Scorchers classic-country songwriting and punk rock musicianship are equal parts sin and salvation, Saturday night and Sunday morning. Ringenberg, still wearing Manuel-meets-Vivienne Westwood glittery suits, wraps himself in a mic chord, tangled up in sin, untangled in redemption.

"I don't know why I can't get free, when I can tell good and well what's best for me," asks Ringenberg in "Self Sabotage," the same question that's been asked in every hamartiology tome since the beginning of time.

The Scorchers (with Baird on bass) ripped through a set heavy with Womack-penned tunes from 1996's Clear Impetuous Morning and 2010's Halcyon Times. Womack joined the band that he once "annoyed to death" and sang "Going Nowhere." Getting into the message of the night, he pointed to himself at the line "Holding my redemption, glad to be alive."

We all were glad he was and that we were, too, because the night ended with a back-to-back punch: the Scorchers leading the crowd in the Nashville anthem "Broken Whiskey Glass" (Womack's favorite Scorchers song, and for that matter, everyone else's) before the entire bill climbed on stage to play "Great Balls of Fire." Ringenberg, Chapman and Lloyd trading verses; Hodges, Kimbrough and Wilder trading guitar parts.

These are people not to be trifled with and when Death comes tapping the shoulder of one of their own, they close ranks and open their arms simultaneously. They want to go to heaven, but not today. There's still plenty of hell to raise here.

Jason and the Scorchers' all-star jam during a benefit for Tommy Womack on Music City Roots, 9/30/2015