The Black Keys weren’t sure they were going to release the results of their December 2019 jam with two veterans from Mississippi’s Hill Country blues scene. After all, the session was so impromptu that they didn’t even know what songs they were going to play. But because Kenny Brown and Eric Deaton had spent so many years playing with Hill Country blues legends Junior Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside, it made sense to pick songs recorded by their former employers.

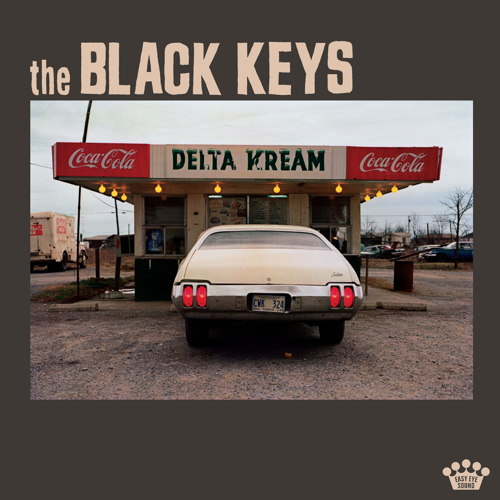

In the end, the Keys decided to release the results as Delta Kream on May 14. Not only because members Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney had first bonded by jamming on this same songbook as teenagers in Akron, Ohio, in 1996. And not only because the two guitars, bass and drums locked into such an exhilarating groove of droning, hypnotic buzz. But because the pair also wanted to repay a debt.

“Yeah, there’s probably zero commercial potential for this record,” Carney admits over the phone from his Nashville home, “but it’s important to put it out now while we still have people paying attention to our band — if only to showcase these guys who did so much to inspire us. I only heard about R.L. Burnside as a teenager because Jon Spencer made A Ass Pocket of Whiskey with R.L. If not for Spencer, who knows when I would have heard of R.L. Maybe we can do the same for some 16-year-old kids today.”

At the tail end of 2019, Auerbach was producing Sharecropper’s Son, a fine album by Louisiana soul-blues singer Robert Finley, out Friday, May 21. The band that Auerbach assembled in his Easy Eye Sound Studios here in Nashville included Brown (Burnside’s longtime guitarist) and Deaton (Kimbrough’s longtime bassist), and the producer was thrilled to be playing with these masters of the Hill Country blues.

“I was having so much fun playing with them,” Auerbach recalls over the phone from the studio, “that I called up Pat and said, ‘You have to come over here.’ We never talked about making a record. It was just that all this fun shit was going on — and we took advantage of it. We didn’t touch a thing, even left the talking in. I hadn’t played these songs in years; we were just throwing them out there. It’s all muscle memory, I guess. We’d do each song twice and usually one was better than the other. I love playing those songs. For me, they’re classics — at least the originals were classics.”

Ten of the 11 songs on Delta Kream were originally recorded by Kimbrough or Burnside, and “Coal Black Mattie” was recorded by both of them. This is not the music of the Mississippi Delta in the state’s northwest flatlands but of the north-central Hill Country, where the rumpled topography created small farms rather than giant plantations, intact communities rather than ghost towns decimated by The Great Migration and a thriving music scene rather than a remembered past. This is a music of one or two chords and a throbbing beat, of a thick bottom sustained against a higher melody. This is the most African music in North America. You can hear that on “Crawling King Snake,” the first single from Delta Kream.

“Junior has as much in common with Ali Farka Touré as he did with John Lee Hooker,” Auerbach adds. “When Junior plays ‘Crawling King Snake,’ it sounds nothing like the John Lee Hooker version. He strips it down to its essentials, and that gives it a great sense of space. Junior was in the middle of nowhere; his juke joint had no other buildings in sight, just rolling hills, a lot of despair and a little bit of joy. All of that’s wrapped up in this music.”

Auerbach and Carney grew up within blocks of each other in Akron, acquaintances but hanging out in different scenes. “He was on the soccer team,” Carney explains, “and I was more of a hippie-rock kid.” Carney’s uncle was Ralph Carney, the saxophonist on records by Tom Waits, Big Star and Galaxie 500, a mentor who opened the nephew’s ears to less-than-obvious music. Auerbach’s dad represented Akron’s leading outsider artist, Alfred McMoore, whose catchphrase, “Your black key is talking too long,” would give the duo their name.

The teenage Auerbach and Carney had different interests, but they overlapped in their enthusiasm for the Hill Country blues records coming out on Fat Possum in the mid-’90s, like the aforementioned Burnside-Spencer collaboration. So when they got together to jam, that’s what they played. It helped that the stripped-down, guitar-and-drums sound of the music fit the two Akronites.

“When I first heard this music,” Auerbach remembers, “I was this little 17-year-old blues fan. All of a sudden here was this music as raw and wild as anything I’d ever heard. It was primal. R.L., Junior and T-Model Ford were to blues as the Sonics were to rock ’n’ roll: wild and deceptively simple. I think Junior and R.L. are every bit as important as Skip James and Howlin’ Wolf.”

The Black Keys’ 2002 debut album The Big Come Up began with a Burnside song, followed by a Kimbrough song. Chulahoma, their 2006 EP, featured six compositions by Kimbrough and was named after the rural Mississippi town where Kimbrough’s juke joint stood. That was their last release on Fat Possum before moving on to Warner Bros. subsidiary Nonesuch and rock ’n’ roll stardom. But Auerbach and Carney both insist that the Hill Country blues has shaped all the music they’ve made.

“Listening to so much Hill Country music,” Auerbach says, “trained my ear how to listen to rhythm and feel, how the guitars and the drums can lock in so tight you can’t tell where one ends and the other begins. And I realized that can be translated to any other style that Pat and I play. I want that to be as true for my keyboardists as for my guitarists in any project we’re doing.”

“It’s the foundation of how we got together and how we play,” Carney agrees. “You listen to an album like Brothers, and it sounds different, but the connection is there: the dirgy feel of that record, the overall dark, spooky sounds all goes back to the Junior shit.”

Sharecropper’s Son, whose sessions led to Delta Kream, is the second album Auerbach has produced for singer-guitarist Robert Finley. It’s not a Hill Country project so much as a classic Memphis soul record in the vein of O.V. Wright. The new wrinkle is the more personal songwriting that Finley brought to the session. He sings of the hard times in the cotton fields on the title track and of the challenges of a backwoods kid in the city on “Country Child.”

“This time,” Auerbach says, “I wanted Robert to come up here and write every song and tell his story, and have a personal connection to every song. He’s an incredible storyteller; he walks in and lights up the room. He’s got that kind of personality. He came to Nashville, and I paired him up with some songwriters I thought would be appropriate: Bobby Wood, Pat McLaughlin and myself. A couple songs Robert improvised on the spot.”

Another Auerbach production released on his Easy Eye Sound label is Smoke From the Chimney, a posthumous release by the prolific singer-songwriter Tony Joe White (“Rainy Night in Georgia,” “Polk Salad Annie” and many more). Tony Joe’s son and manager Jody found his late father’s unreleased vocal-and-guitar songwriting demos and turned them over to Auerbach. These aren’t rejects or leftovers — these are some of Tony Joe’s best songs, even if he never got around to turning them into a polished album, and Auerbach has supplemented the demos with a swampy, funky band.

“What I ended up doing was assembling the same band I would have assembled if Tony Joe was here in person,” explains Auerbach. “Straight-up badass musicians who would have understood Tony Joe’s aesthetic. It was all cut live with his voice in our earphones. Magically, his sense of rhythm was so solid, it was never a problem. ‘Bubba’ might be one of the greatest fishing songs ever. ‘Billy’ and ‘Del Rio’ are so beautiful that any good voice would enjoy singing them.”

Another Auerbach production, Yola’s Stand for Myself, is due July 30. This follow-up to the Grammy-nominated Auerbach-Yola collaboration, 2019’s Walk Through Fire, promises to shift the singer’s focus from self-styled “country-soul” to Memphis soul. Already released is the album’s first single, “Diamond Studded Shoes,” a snappy, sassy R&B number that encourages working folks to fight back against the wealthy parading around in bejeweled footwear.

“We cut right as the pandemic was starting, and things were getting a bit sketchy,” Auerbach says. “We cut it live, with musicians playing as Yola sang. [This album is] way dancier than the other one. Yola wanted to change, but it was a natural change. She’s using her platform and her voice, and I’m just happy to be along for the ride.”

When The Black Keys play the Pilgrimage Music & Cultural Festival in Franklin in September, they promise to bring along Brown and Deaton for a mini-set of Delta Kream songs. Those blues numbers from Mississippi’s Hill Country will provide the key to understanding everything Auerbach and Carney have done throughout their entire career. As Alfred McMoore might have put it, “the black key.”