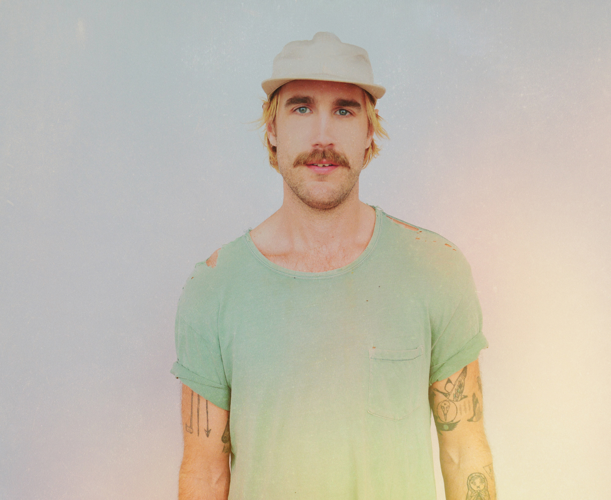

The secret of the success of Wide Awake, the new full-length by Nashville singer-songwriter-rocker Rayland Baxter, lies in how it attempts to depict our current political malaise while honoring the idiosyncrasies of classic British Invasion rock. The record was cut in California with Weezer and Taylor Swift producer Butch Walker, and among other things, it’s an uncanny evocation of The Kinks’ style. Baxter infuses his well-turned compositions with the kind of irony Ray Davies is famous for. Baxter’s new songs are covertly political, and hint at darker ironies that may not seem to belong in straightforward pop music.

Wide Awake never falters in its pursuit of musical synthesis, and it marks a turning point in Baxter’s career. Born in Bon Aqua, Tenn., in 1983, Baxter grew up in Old Hickory and Goodlettsville and moved with his mother to Annapolis, Md., when he began middle school. He went to college at Baltimore’s Loyola University of Maryland, lived in Colorado for a while, and returned to Nashville a decade ago at the behest of his father, well-known pedal steel player and former Bob Dylan sideman Bucky Baxter.

“I wasn’t really finding my way in Colorado like I thought I was going to,” Rayland Baxter tells the Scene from his house in Nashville. Bucky Baxter had co-produced a bluegrass-fusion record by French producer-composer Philippe Cohen Solal, 2007’s The Moonshine Sessions. Rayland came back to Nashville to work as a guitar tech for Solal’s band. After traveling to Paris in April 2008 with the group, he detoured in Israel for six months before finally settling in Nashville later that year.

The younger Baxter had taken up writing during his stay in Israel, and he released his debut full-length, Feathers & Fishhooks, in 2012. That collection of songs performed in a modified ’70s singer-songwriter style was followed by 2015’s Imaginary Man, which featured “Yellow Eyes,” an easy-rolling soul-pop tune that suggested Baxter was operating in the same mode as, say, Lake Street Dive.

Recorded in August 2017 at Walker’s Santa Monica studio RubyRed Productions, Wide Awake expands upon Baxter’s early recordings. Walker’s production hints at the work of John Lennon, The Kinks and Harry Nilsson, while Baxter’s songs are perhaps his strongest to date. He wrote them while living in spartan conditions at Thunder Sound Studio, which occupies a repurposed rubber band factory in the picturesque town of Franklin, Ky.

“I lived in a room about to here,” Baxter says, pointing to a patch of his modestly sized living room. “With a Wurlitzer [electric piano]. I had blanketed the windows, and I had paper all over the walls. It’s a big studio with lots of nooks and crannies.” The resulting songs address such weighty subjects as gun control, crime and romantic obsession. While some of Baxter’s earlier music sounded superficial, Wide Awake manages to be both tough and seductive.

Baxter’s ability to pen political commentary results in “79 Shiny Revolvers,” one of the record’s most John Lennon-esque songs. “Now, everybody talking about it / So we can talk about it now,” he sings. “You really want to save the world, man / Well, I want to save it too.” Baxter underplays the song’s political content, but “79 Shiny Revolvers” subtly reminds listeners that Lennon himself was a victim of gun violence.

If Baxter reveals a knack for the artfully indirect political song on Wide Awake, the record also sounds like great power pop on “Casanova,” a two-chord garage rocker about student loans. Meanwhile, famed steel guitarist Lloyd Green lends licks to “Sandra Monica,” a Kinks-style tune with beguiling chord changes, and renowned percussionist Bobbye Hall also plays on a couple of the record’s tracks.

Wide Awake is high-quality pop that transcends cookie-cutter Americana — Baxter builds songs that gather steam as they proceed, and he cares about such mundane matters as writing good bridges and creating varied arrangements. Baxter’s critique of modern mores is, for the most part, implied throughout the album, though “Hey Larocco” hints at unresolved conflict, and “Casanova” ends with a mournful coda in which Baxter repeats, “Back to the hole that I came from,” until the song ends.

At their best, Baxter’s new songs get within shouting distance of Ray Davies’ character studies, and the music is never less than inventive. Baxter doesn’t ignore the tensions that have turned the American Dream in new directions, but he makes them sound like a lot more fun than they really are.