They were the unlikeliest of collaborators.

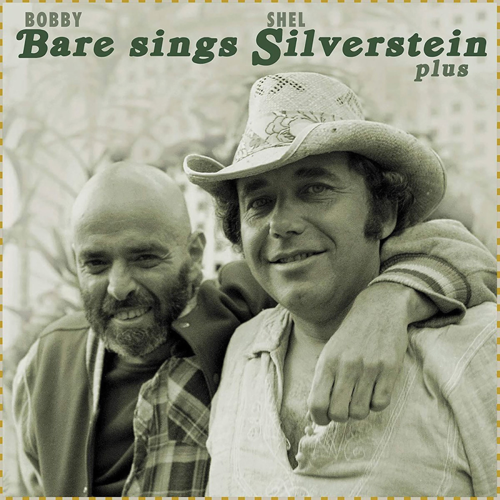

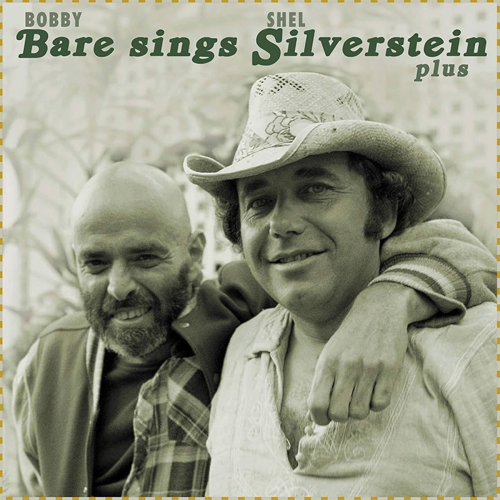

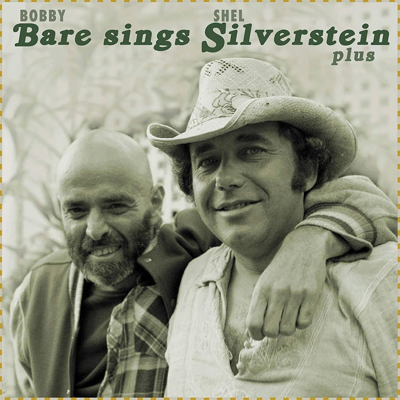

Bobby Bare was a country star raised on the north bank of the Ohio River. Shel Silverstein was a hipster raised in a Jewish neighborhood in Chicago. Bare had curly brown hair and sideburns spilling out of his curled-up black cowboy hat. Silverstein sported a dark beard and was as bald as a brass bullet on top.

And yet Bare released 119 songs written by Silverstein — and a dozen of them were top 30 country singles, including Bare’s only No. 1 hit, 1974’s “Marie Laveau.” Now all 119 of those songs are included in the new eight-CD box set, Bobby Bare Sings Shel Silverstein Plus, which also includes 18 contemporaneous tracks by other songwriters and a 128-page hardcover book.

“Before I ever met Shel,” Bare says over the phone from his home in Hendersonville, “I heard that Dr. Hook song, ‘Sylvia’s Mother,’ and I thought that was a great song — the way phrases ran over from line to line, the way the words were different but flowed really well. I thought it would be a good country song, and I recorded it before I even knew who Shel Silverstein was.”

Meanwhile, Silverstein heard Kris Kristofferson’s “Come Sundown” as sung by Bare and said, “I’d give my right arm if that guy recorded one of my songs.” On one of his periodic trips to Nashville to pitch songs, he met Bare through the latter’s producer at RCA, Chet Atkins, who warned the singer that Silverstein was “a little weird, a hippie type.”

“As soon as you talked to him,” remembers Bare, who’s now 85, “you could tell he was really bright. I soon discovered he was one of the greatest lyric guys ever.”

Silverstein’s intelligence emerged in many different ways. He wrote best-selling children’s books such as The Giving Tree and Where the Sidewalk Ends, drew cartoons for Playboy, wrote off-Broadway plays, and co-wrote the screenplay for Things Change with David Mamet. But Silverstein’s favorite singer was Ernest Tubb, and he wanted to be a country performer. The problem was, he couldn’t sing.

“He screeched,” Bare says. “One time we were working on some songs over at the Holiday Inn on West End Avenue. I was going over the melodies to make sure I had them right. Around 11 at night, I didn’t have one right, and Shel grabbed the guitar and started singing the line. All of a sudden, a woman was banging on the wall screaming, ‘Shut the fuck up.’ I said, ‘Shel, I’ve been singing for hours and we haven’t heard a peep. You sing one chorus and you wake up the whole damned hotel.’ ”

Bare, though, had a honeyed tenor that could turn the brilliant lyrics and ugly-duckling vocals on demos by Harlan Howard, Bob McDill and Tom T. Hall into things of beauty. He had that rare combination: a good voice and good taste in songwriters. Even rarer was his conviction that funny songs were just as important as serious songs. Silverstein could write both.

Rarest of all was Bare’s ability to listen to a Silverstein demo and discern the music that the writer had in mind, even if it didn’t all get onto the tape. Quite a few country singers recorded Silverstein’s songs — most notably Johnny Cash (“A Boy Named Sue”), Emmylou Harris (“Queen of the Silver Dollar”), Loretta Lynn (“One’s on the Way”) and Waylon Jennings (“The Taker,” a co-write with Kristofferson) — but Bare became Silverstein’s favorite interpreter.

“He couldn’t always play it or sing it,” Bare explains, “but he could hear it all in his mind, and I was one of the few people who could understand what he was hearing and translate it into a record. That’s the reason I recorded so many of his songs. At the bottom of it all was the fact that I loved Shel’s songs, and Shel loved my singing. We spent so much time together — getting to know each other and respect each other — that Shel became part of the family.”

Bare had something else as well: artistic ambition. “I heard that Joe South album Introspect, and I loved the album so much,” he recalls. “Not only did it have great songs, but they all tied together into a whole story. Then I heard that album The Very Special World of Lee Hazlewood, which did the same thing. I was tired of putting out albums that had maybe one hit on it and the rest of the songs were rejects. Those albums were so uninteresting, but that was the standard way of doing things in those days.”

Bare asked all his songwriter friends in town — Harlan Howard, Willie Nelson and Hank Cochran — if they would write a full album of interconnected songs, but all they would offer were one or two potential singles. In early 1973, during the annual Country Radio Seminar — a time when hundreds of disc jockeys, label execs, songwriters and artists got drunk and formed bonds — Bare found himself sitting next to Silverstein at a Harlan Howard party on a Saturday night. The singer lamented that no one would write him an entire album.

“On Monday I was at my office downtown,” Bare recalls, “when Shel called and said, ‘I’ve got your album.’ He was back in Chicago at this point. I said, ‘When can I hear the songs?’ and he said, ‘How about today?’ He flew down that same day and started singing me ‘The Winner.’ I was laughing so hard, I made him stop in the middle, so I could catch my breath and hear the rest of the song. He played one great song after another, and that became the album Lullabys, Legends and Lies.”

That 1973 two-LP set was a landmark in country music history. Not only was it a collection of songs that all related to the title track in some way, but it was also produced by Bare himself without label interference. It inspired other such independent, unified concept albums as Jennings’ Honky Tonk Heroes and Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger, thus setting an important precedent for the outlaw country movement. Just as importantly, it launched the Bare-Silverstein partnership that remained active through 1983. Silverstein died in 1999.

One of the hits from Lullabys was “Daddy, What If,” a duet between a young son full of questions and his patient father, which Bare recorded with his actual first-grader son, Bobby Bare Jr. After the tracks were recorded without an audience, Silverstein had the idea of playing the tapes for an in-studio audience that could respond to the music and to Bare’s song introductions. The result was a “fake live” album.

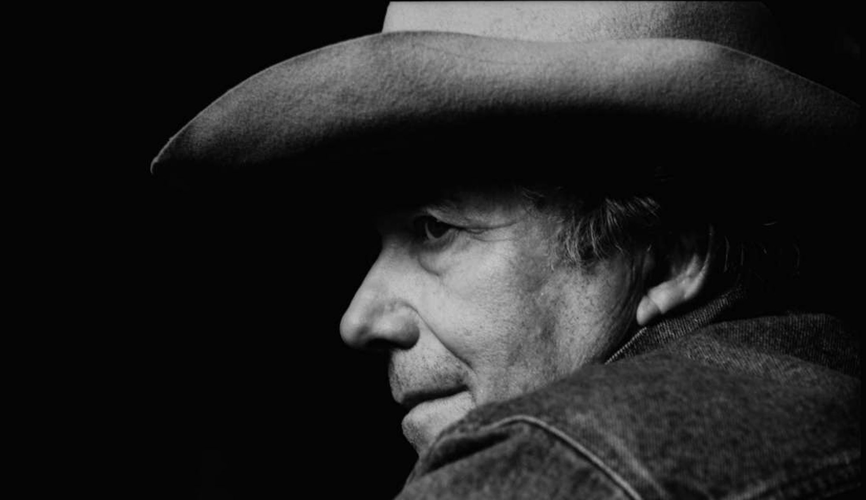

Bobby Bare

In the introduction to “Daddy, What If,” Bare says, “I’d like to introduce you to the next superstar. Twenty years from now, he’s going to be so ashamed of what he has done on this record that he’s probably going to sue me. He and all of his friends will be sitting around stoned, and he’ll say, ‘Look at what the old man made me do.’ ”

Contrary to his father’s prediction, however, Bare Jr. remained proud of the record, keeping a photo of his 7-year-old self onstage with his dad and Silverstein at Exit/In through his teen years. That positive experience led him to his own career as a professional musician. The father and son co-produced the 2010 tribute album, Twistable, Turnable Man: A Musical Tribute to the Songs of Shel Silverstein, featuring lead vocals by John Prine, Ray Price, Lucinda Williams and both co-producers.

Of the 119 Silverstein compositions on the new box set, which will be released Friday via the archival label Bear Family Records, 96 were written by the man alone. The other 23 were co-written, and the most frequent co-writer was Fred Koller. (Full disclosure: I have co-written a handful of mostly unrecorded songs with Koller.) Koller, who also wrote or co-wrote such hits as Kathy Mattea’s “She Came From Fort Worth” and Jeff Healey’s “Angel Eyes,” still lives west of Nashville and owns Rhino Booksellers in town. He wrote dozens and dozens of songs with Silverstein. Seven of them appear on the box set, while many are unreleased.

“Shel didn’t drive,” Koller recounts, “and one day he needed a ride out to the original Bradley’s Barn to pitch some songs to Owen Bradley during an Ernest Tubb session. If you were a young kid in Nashville, wouldn’t you want to drive Shel Silverstein to hear Ernest Tubb? We pretty much wrote our first song, ‘Jennifer Johnson and Me,’ during that ride. He was that fast, constantly throwing out ideas, completely open to however outrageous you could get. He just loved wordplay.”

“Jennifer Johnson and Me” is on Bobby Bare Sings Shel Silverstein Plus, along with the four complete Bare-Silverstein concept albums. There are also two Columbia albums full of Silverstein songs, plus two discs of Silverstein songs scattered across various Bare albums and singles.

One of the concept albums is Great American Saturday Night, the planned 1977 sequel to Lullabys. Once again, Silverstein wrote all the songs (including two with Koller), and once again the audience was added later. But Bare was on his way out the door to sign a new contract with Columbia, so RCA killed the record. It wasn’t released until this year, when BFD Records put out a stand-alone 13-track version. Bobby Bare Sings Shel Silverstein Plus has the full 16-track version.

“They needed each other,” Koller says. “Shel wrote wonderful, wonderful songs, but Bobby took the rough edges off. He knew how to make them listenable.”