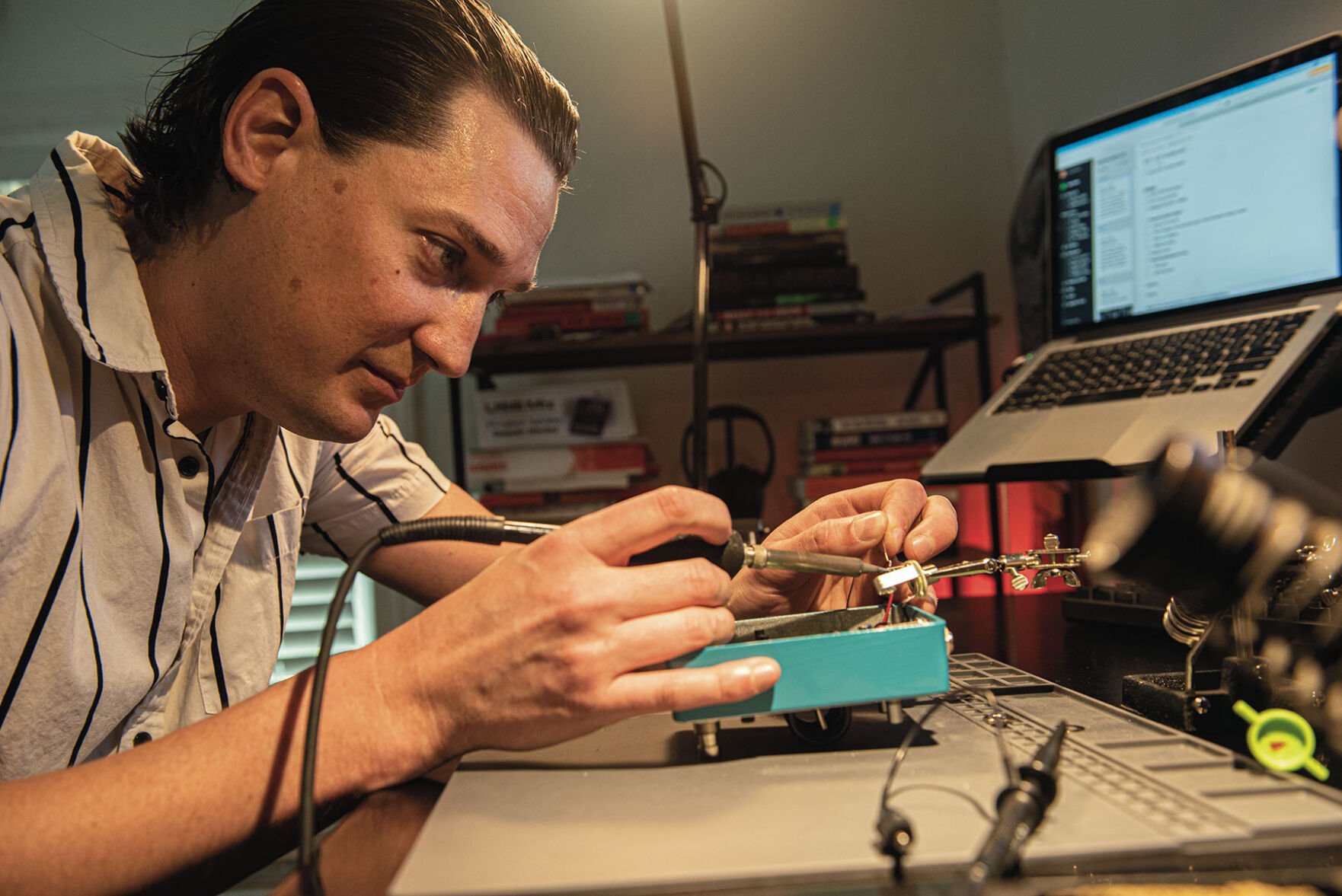

Jesse Rude

Washington’s trade war has sent Nashville’s small-batch gear makers and working musicians scrambling. Costs are climbing, indie shops are reeling, and the little guys are left holding the bill.

For Jesse Rude, founder of boutique guitar effects company Rude Tech, the breaking point came earlier this year.

“I make pedals and wholesale them to stores and sell them directly to customers on my website,” says Rude. “I was doing that full time for over a decade. But in March I took a job. It’s all because of the tariffs. …

“Back in February, I made an order for prototype circuit boards. It was about 40 boards — much smaller than a typical production run — and the product itself was supposed to cost about $76. The delivery guy came and I had to pay [an additional] $125 just to get them. He was trying not to say the word ‘tariff’ — probably because he’d had that conversation with a lot of people that day and they were getting mad. But he kept stressing it was money owed to the government, and he couldn’t drop the package off until I paid online.”

What stings most, says Rude, is the seeming randomness of it all. “My order got hit hard,” he notes. “But my friend’s far bigger order that landed two days later — he didn’t even get charged at all. It felt so arbitrary.”

Economists will tell you his story reflects a wider problem. In 2018, a University of Chicago survey of 43 leading economists found that 93 percent disagreed that Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs would raise Americans’ welfare, and none agreed. New analysis from Yale’s Budget Lab shows the 2025 tariffs are raising consumer prices — particularly on lower-income households — while providing only narrow, sector-specific benefits and no net job or income gains overall.

Meanwhile, inequality remains elevated. In February, The Wall Street Journal reported that the top 10 percent of earners account for nearly half of all U.S. consumer spending — the largest share since records began in 1989, according to Moody’s Analytics. On the shop floor, Rude found that even “buying American” paradoxically often involves overseas manufacturing.

“People ask me, ‘Can’t you just get this stuff made in the U.S.?’” Rude says. “I order from Norman, Okla., and Cincinnati, Ohio — and the aluminum is mined and cast in China. So a guy in Oklahoma sells it to me, but his product is coming from China.”

For Rude, there was no easy work-around. The result was a punishing cost-to-price multiplier. He says he has to charge four times his construction costs to cover his pay, taxes and expenses. While Rude stepped away from building pedals full time, he still makes them on the side.

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments on the tariffs Nov. 5, with a decision expected in early 2026. Until then, unpredictability rules. “That’s the hardest part,” Rude says.

At Eastside Music Supply, co-owner Blair White has watched the burden shift onto musical instrument shops like his. “We’re the ones paying the tariffs — not China, not Mexico,” says White.

The Trump administration argued that tariffs raise the price of foreign goods, encouraging companies to manufacture in the U.S., which it says will create jobs and lower costs for Americans. But when it comes to small electronics, White doesn’t see that happening anytime soon. “To build the factories, hire the people, get the know-how — it would take years,” says White. “And it would still cost more.”

For him, the stakes go beyond gear. “I have 10 full-time employees here that spend their money in the community because they live here, so all that cycles back,” says White. “Those dollars stay in the neighborhood.”

One of Eastside’s employees, manager Taylor Wafford — also the Nashville musician behind Blood Root — has watched the basics get pricier.

“Good [amplifier] tubes are almost impossible to find for a reasonable amount,” Wafford says. “And the quality has plummeted. The only time I’ve ever seen strings increase has been in the last year — about $2 a pack.”

Angela Lese

Angela Lese, drummer and social media manager at Fork’s Drum Closet, sees the same trend.

“At Fork’s we’ve seen prices jump across the board — cymbals, snares, hardware, even foam for drum cases,” says Lese. “And shipping has gone up too.”

The shop is owned by Steve Maxwell, who also has stores in Manhattan and Chicago. For Lese’s band Lips Speak Louder, merch costs have ballooned.

“If we had to ship a T-shirt and a vinyl record, instead of costing 6 or 7 bucks, sometimes it’s $15 or $16 nationally,” she explains. “Overseas it has probably tripled.”

The economics of shipping as an indie can be brutal. Recently announced FedEx and USPS hikes average 6 to 7 percent. Indie artists don’t get bulk discounts or negotiated rates; they can’t spread costs across vast economies of scale like Amazon — whose in-house logistics network includes a cargo airline that is big enough to carry other retailers’ shipments — or the big-box chains. Boxes and packing materials cost more too when you’re not buying by the pallet. A modest bump on paper can balloon into twice the price.

Practical tips for navigating changes in trade policy that are increasing costs on even cheap shipments from other countries

And then came the death of de minimis, the trade rule that once let imports under $800 slip in duty-free. That exemption vanished on Aug. 29. Now every overseas package is treated like a standard import, subject to tariffs, fees and customs paperwork.

The White House insists the change will close loopholes, curb fentanyl shipments, raise revenue and give U.S. manufacturers a fairer shot. But in Nashville’s indie scene, it has meant slower deliveries, shortages and higher costs.

“We used to order from Canada and keep it under the limit,” says Eastside Music Supply’s Blair White. “But that’s changed. One of the manufacturers we work with — they make the patch cables we like — had to raise prices because they’re getting hit with the fees too.”

Aaron Lee Tasjan at The Groove on Record Store Day, 4/12/2025

Musicians are improvising. Some repair old gear instead of buying new. Others sell instruments to make rent or gas. Bands talk about shortening tours, skipping markets or doubling up on bills to keep ticket prices low. “The fallout from it is affecting musicians, especially in Nashville,” says Lese. Aaron Lee Tasjan, a Grammy-nominated Nashville artist who proudly calls himself a working-class independent musician, says tariffs are reshaping access to music itself.

“A lot of those instruments are manufactured with parts made in Mexico or China,” he says. “What used to be the most affordable instruments are no longer as affordable.”

He points to the market for students. “A trumpet that used to cost $600 is now almost a thousand bucks,” says Tasjan. “For a family trying to help their kid pick up a decent instrument, that can shut the door before it opens. What if that kid falls in love with music? If families can’t afford it, kids lose the chance before they even start.”

The same arithmetic is crushing touring musicians. “Costs are so much higher now that I’ve had to rethink things,” Tasjan says. He’s referring to dates he has planned throughout the fall in his ongoing 10th anniversary celebration for his debut solo LP In the Blazes. “Instead of doing another band tour, I’m doing a solo run.”

The decision wasn’t about preference, but survival. “A side musician I would have hired for $300 a show is telling me they need $400 to make it work. And I get it — they’re dealing with higher costs of living. But if I pay everyone that rate, I am losing money. So, you either scale down or you don’t go out at all.”

Tim Easton

Tasjan isn’t the only one working the abacus. Nashville songwriter Tim Easton, who spends about a third of the year on the road, is absorbing the blow too.

“Where I run into trouble is people getting hit by higher grocery bills, things that keep them from going to a show or buying merch,” says Easton, speaking from a tour stop in Alaska. “Music is basically free already. But now fans are counting pennies before they even think about buying merch.”

Independent shops know they can’t roll back prices. “Independent music shops aren’t in control of price hikes — it’s coming from the companies,” Angela Lese of Fork’s points out. “We’ll always try to help musicians, but I don’t see prices ever going down. Why would they drop prices when they’re selling what they can now?”

The winners and losers of tariffs aren’t hard to spot. Corporations and big players can absorb the shocks — or deploy a phalanx of K Street lawyers to carve out exemptions. Indie builders, musicians and mom-and-pop shops don’t have that option. They scale down, or they walk away. And in Nashville, where music is the city’s lifeblood, the indies are bleeding.

Our two-part look at the Trump administration's trade policies and their impact on local independent music