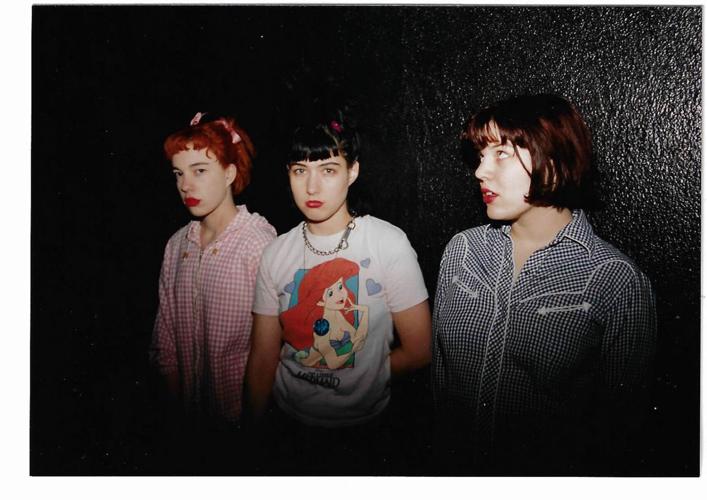

Bikini Kill, 1990s

Kathleen Hanna and Bikini Kill started a riot in the ’90s, and they’re back to do it all again. The legendary feminist punks and co-founders of the riot grrrl movement reunited in 2019, and they’re back on the road once more. The band’s show Thursday at Marathon Music Works, delayed from a planned 2020 date, will be their first in Nashville since they played the famed Lucy’s Record Shop in November 1994. The Scene checked in with Hanna — sporting her trademark purple lipstick — via video conference about the band’s choice to reunite, how crowds have changed since the ’90s and more.

Bikini Kill has just gotten back to playing shows together in the past few years, which I’m personally super excited about. Why did now feel like a good time for a comeback? Was it a personal decision or more of a social responsibility decision?

I think it’s a little bit of all of it. But, like, everything that has ever happened in Bikini Kill — it was largely personal in that I had an opportunity to get back together with two people that I love. Probably more than almost anybody on the planet who I care so much about, and who I’ve been through a very strange experience with in the ’90s. Being in the band was really surreal. And so to be with people who went through that experience, we went through that experience together. It was a time in my life where I really needed that — like, I really needed to be with them.

And so to me, it was a lot more about the friendships than about even the band or the music. And then when we started doing the songs, that’s when it really became about a social imperative.

Yeah, it’s like coming home.

I felt new vigor in the songs. I’ve said this a million times, but 15 years ago, it’s not that the world wasn’t as fucked-up. I mean, it wasn’t, but I wasn’t in touch with the part of me that could sing those songs. And now I am.

In preparation for this story, we found a zine that includes an interview from when you played Lucy’s in the ’90s. Something it specifically mentioned was that there were young girls at the show — sixth- to 11th-graders. How have you seen the crowds change in recent years, both demographic-wise and in terms of energy?

We’ve seen the audiences — they’re very, very intergenerational. Little kids all the way up to people in their 70s sharing space with each other, which is amazing. Definitely more people of color, more BIPOC people at the shows.

So we’ve seen the audiences change, but I think the remarkable thing is — I sort of thought it was gonna be people who saw us in the ’90s, who were like, “Oh, I wonder what they sound like now.” But it’s a lot more young people who were like, “I never got to see them. I’d love to check it out.” You know? And then the people who saw us in the ’90s are bringing younger people. They’re like, “Here, this is what I was into.” Or, “This is the band I hated in the ’90s, but I based my identity off hating them.”

The “girls to the front” thing was cool when there are, you know, just a few women there. But one of the things I realized over the years is that the cool guys just went to the back because they were like, “Hey, I want to be respectful.” I never got to see their faces, and I never got to interact with them. I’m interacting with supportive cisgender men a lot more than in the past, and that feels good. There’s still some like jerks who harass people who come, but it’s way less. And the fact that the audience is more supportive, more than what the makeup is, has been the biggest change.

A problem we’ve been having in Nashville is that our alternative spaces are disappearing. What role do you think independent venues and alternative community spaces play in your life and the lives of people you interact with?

It’s huge. I mean, having an independent music scene — these are the incubators of the great ideas of the future, you know what I mean? Like, these are the bands that are going to change people’s lives, that are going to have these shows that make somebody be like, “I can do this dream that I have.”

I mean, not to be too Disney about it, but … I remember seeing [Japanese rock band] the Boredoms in Seattle, and feeling like they just cleaned my brain, you know? Like, it wasn’t a feeling of “I can do anything.” It was just like I was inside art, because their music was this art that was surrounding me. And I was inside of the art that they were making, and it was such a magical, otherworldly feeling that you don’t get to usually experience when you’re grocery shopping, or driving your car, or whatever.

And those things aren’t going to happen if Clear Channel owns everything. It’s not. It’s really hard to put on all-ages shows. It’s hard as a band to play all-ages shows, because of capitalism. … I feel for the club owners because they make money off alcohol. But it’s like, the underground culture is where it all comes from. Yeah, doesn’t come from corporations, it comes from you — it comes from kids.

Bikini Kill at Hollywood Palladium, 2019

There has been backlash about the riot grrrl label, and whether that’s inclusive of trans women and people of color. Do you think the world still needs riot grrrls? Has the meaning of “riot grrrl” changed, or does it need to be something else?

I think it’s really up to each individual person if it’s something that they identify with. And one of the things that we did that I think was smart was that it was open for everybody to interpret the way they wanted to interpret it. And the idea was everybody owned it, and everybody could make what they wanted.

I definitely feel like riot grrrl today — if it’s not trans-inclusive, fuck it. If it’s not inclusive of all different kinds of women, fuck it. I don’t want to be associated with shit like that. But it’s really — I don’t own it.

If there’s a girl in Tennessee who’s 13 years old, who finds it useful to say “I’m a riot grrrl,” great, you know what I mean? But I believe it can evolve and change. But I would love for people to have a different name and to accomplish something brand-new that’s their own, so that they don’t have to deal with the legacy of our mistakes. And they can make their own mistakes and not constantly be creating in opposition to our mistakes — which was not being intersectional enough.

Last year, Tennessee’s state legislature enacted a nearly total ban on abortions, and recently passed a bunch of anti-LGBT laws. Is there anything you want to say to people who are feeling disillusioned about what’s happening in their home state right now?

We’re specifically making the decision not to boycott places that have abortion bans, or bans on books, or bans on drag performance. Because we’re not going to let those fuckers tell us where we can and cannot go. And we feel like we’re most needed in those places as a site of community-building.

All I can say that’s positive is that these people know this is their last gasp, right? Like, they are the mouse that fell into the milk and they’re trying to make butter out of it. But these rats are not going to make it out of the bucket. You know, we’re not going to let them make it out of the bucket. They are struggling, they’re hanging off of cliffs. They know their time is up. They know that they’re old men and it’s a young women’s world, and they are fucked.

I’m currently working on a film about my second cousin Darcelle, who’s the oldest living drag queen in the United States. [Editor’s note: After this interview, Darcelle XV died at age 92.] And so definitely, the drag stuff has a specific meaning to me, because he was the only person in show business — in my family — who supported me and told me that I was good at what I did.

And so the attacks on drag performance really hit home for me, because these are people who are role models in the community who are being penalized. And they already have to live in fear for many other reasons, and they don’t need this added shit.