Jeremy Ivey isn’t one to let the grass grow beneath him. In September 2019, the veteran singer, songwriter and producer released The Dream and the Dreamer, his first solo album. The country-infused, rock-kissed songs on that critically lauded LP — a product of many years of writing, recording and touring — were already written when much-loved, wide-ranging independent label ANTI- Records expressed interest in signing Ivey in September 2018.

“Once I’d signed the record deal, I took the money they gave me and immediately put it into [booking] the studio,” Ivey recalls, speaking with the Scene by phone. “I’d never been in an actual recording studio to do my own thing. I had never really written for an album for myself before, because I didn’t think anybody had any interest.”

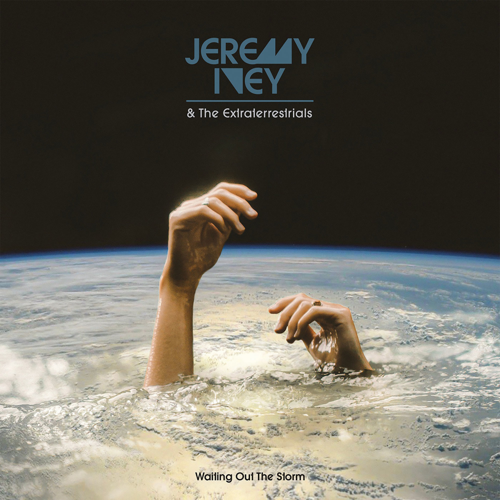

But no sooner had the ink dried than he began work on a new batch of songs. They make up his new LP Waiting Out the Storm, out Oct. 16. Ivey made the album alongside wife and closest collaborator Margo Price. Not long after the sessions for her own recent album That’s How Rumors Get Started, which she co-produced with Sturgill Simpson, Price produced Waiting Out the Storm and sang backing vocals on several of its tracks. The pair and Ivey’s band The Extraterrestrials recorded the album over the course of three days in February 2019 at Nashville’s Sound Emporium Studios.

Waiting Out the Storm opens with “Tomorrow People,” a jangly, psychedelic number with vocals reminiscent of Lou Reed. The track considers how future generations will live in the wake of the turmoil we’ve been living through in recent years. Among other pointed questions about mental health and climate change, Ivey asks: “Hey tomorrow people, do you still blame the shit you do on different-colored people who are not just like you?”

“I was in this antique bookstore and I saw this sci-fi book called Tomorrow People,” says Ivey. “I didn’t open it up to see what it was about. I thought, ‘Oh, this is a song — it’s a letter to the future.’ I went home and got a notebook and wrote it out. Margo helped me with a couple of lines — she had the ‘virtual sex’ line, and ‘Have you found a pill that works?’ I like that it has a point and a message but isn’t in your face. It’s heartfelt, too. If you could talk to your great-grandkids, how would you apologize to them about the stains you left both on the earth and on people’s psyches?”

Though Ivey wrote the material two years ago, the nine songs that follow “Tomorrow People” are similarly prescient, deconstructing the ills of the day — among them racism, xenophobia and the growing wealth gap — with a critic’s precision and a poet’s compassion. The album doesn’t take sides, though, as Ivey sees the hatred fueled by growing political division as one of the most destructive forces currently at work in American society.

“I may get a little shit for that sentiment, but I’m really heartbroken for how America is now,” he says. “I know it was that way when I was a kid, but it wasn’t this strong. There were people who saw the good in what the other side was doing. … It’s so toxic now. I have nothing against anyone because of their political beliefs. Everyone goes through their own individual thing. I just don’t want people to be hateful to one another.”

A standout moment on Waiting Out the Storm is “Hands Down in Your Pockets,” a four-minute journey through the ravages of income inequality and “headless headlines.” It’s delivered in a rapid-fire style that evokes spoken-word poetry and the mid-Aughts solo work of T Bone Burnett. Ivey, Price and the band got creative in the studio to build a soundscape that fit the freewheeling nature of the lyric.

“I wrote the verses for that all at once,” Ivey says. “I liked it because it was weird and abstract but still pointed. … When we were in the studio, I said to [Extraterrestrials guitarist Alex Munoz], ‘I want to hear you get pissed off.’ He has that really wild guitar sound, which I love. And we didn’t have an organ, so I put my harmonica through a Leslie speaker.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has been difficult for the music community as a whole but particularly harrowing for Ivey, who contracted the virus in the spring and was seriously ill for several months. He explains that the experience made him come face to face with his own mortality in a way he never had before, and that doing so has forever changed his outlook on life.

“It’s cliché, but it made me enjoy and appreciate little things in my life that I may have overlooked,” he says. “Being that close to what I consider death — I’m the type of person who thinks about my mortality quite a bit, but when you have to face it, it’s different.”

Ivey remains busy as ever. He says that he and Price both have full LPs’ worth of new material ready to go, and hope to find ways to record the new music safely with their bands in the coming months. For the foreseeable future, Ivey says, he plans to release a new album each year “until people don’t give a shit anymore.”