On the wall of Michael Gray’s office at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, there’s a framed Hatch Show Print poster for a 2011 panel discussion at the museum titled Land of 1000 Dances: The Groundbreaking Sounds of Muscle Shoals. According to Gray, who is vice president of museum services, that panel was the inspiration for the museum’s new featured exhibit, Muscle Shoals: Low Rhythm Rising, which begins a run of more than two years Friday.

“After that panel, I just remember thinking, ‘Oh boy, we gotta do an exhibit on this,’” recalls Gray, the exhibit’s co-curator. “So it’s something that we’ve been building toward for a long time, but I would say it was about three years ago when it got the green light.”

That 2011 panel included Rick Hall, David Briggs, Dan Penn, Norbert Putnam, Spooner Oldham, Candi Staton and Donnie Fritts, all of whom are featured prominently in the new exhibit occupying the museum’s 5,000-square-foot second-floor gallery used for featured exhibits.

Muscle Shoals is best known for R&B and rock recordings, so anyone not familiar with the museum’s history might wonder why it’s spotlighting a recording center with tenuous ties to country music. But as the museum has shown with three of its previous exhibits over the past quarter-century — Night Train to Nashville: Music City Rhythm & Blues 1945-1970; Dylan, Cash, and the Nashville Cats: a New Music City; and Western Edge: The Roots and Reverberations of Los Angeles Country-Rock— the institution is not strictly confined to country music.

“I think the hall’s mission in some ways is about American music, period,” says museum writer-editor and exhibit co-curator RJ Smith. “American music that’s been influenced by all sorts of things.”

Muscle Shoals’ rise to become an important recording center is an especially American story — an unlikely rags-to-riches tale that in many ways is the embodiment of the American Dream. The exhibit covers this story from “Father of the Blues” W.C. Handy, who was born in Florence, Ala., in 1873, to Arthur Alexander, who in 1962 brought the Shoals its first national recognition as a recording center when he hit the Top 40 with “You Better Move On,” and on to the present, where it remains a nearly mythical recording destination for the likes of Drive-By Truckers, Jason Isbell, The Black Keys, John Paul White of The Civil Wars, The Mekons’ Jon Langford and others.

What is popularly thought of as “Muscle Shoals” is actually the Quad Cities of northwest Alabama located along the Tennessee River — Florence, Muscle Shoals, Sheffield and Tuscumbia. There had been recording in Florence since the mid-’50s and some locally successful sides recorded for the Tune label — most notably Junior Thompson’s “Who’s Knocking?,” described by co-curator Smith as a “rockabilly hallucination,” and “A Fallen Star” by future Alabama state Sen. Bobby Denton. But there had been no professional studios until 1960, when Rick Hall opened the now-legendary FAME Recording Studios.

“There was a guy who built a studio in his garage and another guy would record in the waiting room at the bus station on Sundays when the buses didn’t run, but I don’t consider those real studios,” says Putnam, who was the bassist in the original Muscle Shoals rhythm section. “Rick Hall built the first real studio here.”

“I always tell everybody, ‘Hey, if it wasn’t for Rick Hall, none of us would be out here,” says hit producer-songwriter Dan Penn, who got his start at Tom Stafford’s publishing company Spar Music, located above the City Drug Store in Florence.

While Hall was the man of action who almost single-handedly willed Muscle Shoals to national prominence, it was Stafford who first saw the potential for making hit records there.

“The first guy that said ‘We can have hits out of here’ was Tom Stafford,” Penn says, “He was like that. He talked a lot, and he said a lot, but he also envisioned a lot. And this was back in ’58, ’59 and ’60.”

Along with Billy Sherrill — Hall’s former bandmate in a late-’50s rock ’n’ roll group called The Fairlanes — Stafford and Hall launched a new publishing company in 1959 called Florence Alabama Music Enterprises. After Sherrill quit the following year and moved to Nashville, where he would eventually become a Country Music Hall of Famer for his work as an engineer and producer, Hall took over sole ownership of the business and shortened the name to the acronym FAME.

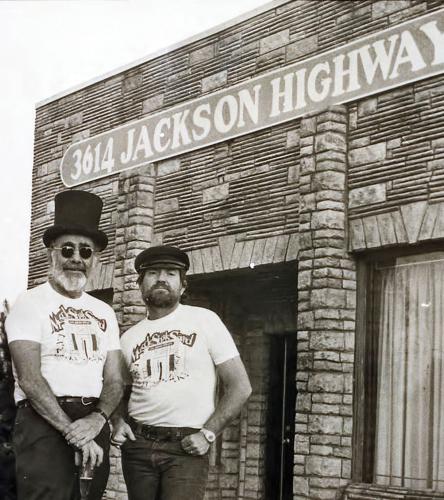

Jerry Wexler (left) and Willie Nelson outside Muscle Shoals Sound Studio, 1973.

Hall opened FAME Recording Studios in a former tobacco and candy warehouse outside Florence near the Wilson Dam. Working with the first Muscle Shoals rhythm section — guitarist Terry Thompson, keyboardist Briggs, bassist Putnam and drummer Jerry Carrigan — Hall produced the area’s first hit, Alexander’s aforementioned “You Better Move On,” which was released by Dot Records in December 1961. The record hit the Billboard Top 40 at the end of March 1962 and climbed to No. 24 during a six-week stay on the chart.

With the money he earned from “You Better Move On,” Hall moved FAME studios to its current location in Muscle Shoals. Over the next three years, a number of pop and R&B hits came out of FAME — including “Steal Away” by Jimmy Hughes, “I’m Your Puppet” by James and Bobby Purify, “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am)” by The Tams, “Everybody” by Tommy Roe and “Hold What You’ve Got” by Joe Tex — all featuring FAME’s hot young rhythm section.

Barely in their 20s, Briggs, Putnam and Carrigan moved to Nashville at the end of 1964 upon the promise of significantly more session work. Understandably, the loss of his rhythm section came as a blow to Hall. After all, it was the rhythm that was attracting artists to Muscle Shoals — that swampy, swingin’ rhythm.

“I was one sad boy,” says Penn of learning his former bandmates in Dan Penn and the Pallbearers were leaving. “It was a surprise to Rick, and it was a surprise to me. But just to show you what kind of man Rick was, he could not be stopped. He just went and got him some more cats.”

Those cats — guitarist Jimmy Johnson, keyboardist Barry Beckett, bassist David Hood and drummer Roger Hawkins — would become the second Muscle Shoals rhythm section, which was known as The Swampers. Over the next five years, The Swampers played on a slew of Top 40 hits at FAME, including Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” Etta James’ “Tell Mama,” Wilson Pickett’s “Land of 1000 Dances” and “Mustang Sally,” and Clarence Carter’s “Slip Away.”

After a financial dispute in 1969, The Swampers left FAME to form their own studio, Muscle Shoals Sound, where they would continue to back a string of hitmakers. They accompanied The Staple Singers on “I’ll Take You There” and “Respect Yourself,” Paul Simon on “Kodachrome,” Leon Russell on “Tight Rope” and R.B. Greaves on “Take a Letter Maria.”

With the departure of The Swampers, Hall once again got “some more cats.” The third incarnation of the FAME rhythm section was called The Fame Gang, and the hits kept coming. The lineup featured guitarist Junior Lowe, keyboardist Clayton Ivey, bassist Jesse Boyce, drummer Freeman Brown, multi-instrumentalist Mickey Buckins and the Muscle Shoals Horns — trumpeter Harrison Calloway Jr. and saxophonists Ronnie Eades, Harvey Thompson and Aaron Varnell.

The success of FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound inspired the opening of a number of other studios in the area in the 1970s. There were noteworthy recordings made at several of them, including The NuttHouse (which hosted sessions for Jason Isbell, The Blind Boys of Alabama and The SteelDrivers, among others), Music Mill (Hank Williams Jr., Narvel Felts), Wishbone (Hank Williams Jr., LeBlanc & Carr) and East Avalon (The Forester Sisters, Clarence Carter).

By the end of the ’70s, Tom Stafford’s vision of making hit records in the Shoals had come to full fruition. Muscle Shoals: Low Rhythm Rising tells the story of the men and women who made its fulfillment possible.

“To me it’s all about the area, the environment, the land, the soul that’s so obvious down there in the people and the players, and we were tapping into that,” says the museum’s vice president of creative Warren Denney, who had a lead role in the creation of the exhibit and its catalog, and in producing all the original videos featured in the gallery.

When you enter the Muscle Shoals: Low Rhythm Rising exhibit, you see a video screen featuring a photo montage that gives visitors a preview of the exhibit set to the song “Land of 1000 Dances,” Wilson Pickett’s 1966 pop and R&B hit cut at FAME. Then, when you enter the exhibit’s main gallery, there’s a mini theater with benches where you can watch a film narrated by Isbell that sets the stage for the entire story.

There are three other video screens. Two of those screens mix vintage audio and video clips with film interviews featuring Putnam, Penn, Oldham, Staton, Isbell, White, Rick Hall’s wife Linda and son Rodney, recording artists Jimmy Hughes and Bettye LaVette, Swampers bassist David Hood and his son Patterson (a founding member of Drive-By Truckers) and others. The third screen shows clips from the 2013 documentary Muscle Shoals.

The exhibit also includes two digital interactive stations where visitors can access five sections: a jukebox with more than 60 classic Muscle Shoals sides; a section for behind-the-scenes songwriters like Penn, Fritts and George Jackson; a section for the legendary session musicians; info on 13 Muscle Shoals-area studios; and a section featuring the oral history interviews for the project.

Among the hundreds of historic items showcased in the exhibit, here are a few highlights:

• The Apollo baby grand piano played by Aretha Franklin and others in recording sessions at FAME Recording Studios from 1961 through 1970. Franklin used the piano on her Top 10 hit “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You).”

• Wilson Pickett’s black long-sleeve polyester jumpsuit with flared legs and clear gems on the sides, black belt with gems, and black leather ankle boots with side zippers, which he wore on the cover of The Best of Wilson Pickett Vol. II.

• A 1964 Fender Stratocaster guitar formerly owned and played by Duane Allman when he worked as a session player at FAME Studios in 1968. Allman traded it to Mickey Buckins for a Fender Telecaster, and since then, Buckins has used the Strat on sessions and live performances.

• A 1957 Fender Telecaster owned and played by Duane Allman and Pete Carr, Allman’s bandmate in Hour Glass. Allman wanted to play with a fuzz effect, so he drilled holes in the guitar to attach a fuzz unit he could control while playing.

• A 1970 Telecaster once owned by Roebuck “Pops” Staples of The Staple Singers, which you can briefly see him play in The Band’s concert film The Last Waltz. The stunning dark grain of the rosewood body is accented by a simple black pickguard.

• Three identical tie-dye floor-length jumpsuits with gold corded bows accented with red, orange and green gemstones, which were worn by Cleotha, Yvonne and Mavis Staples of The Staple Singers.

• A 7-inch of Alexander’s first release, a single for Judd Records featuring “Sally Sue Brown” backed with “The Girl That Radiates That Charm.” Because he was Arthur Alexander Jr., his friends called him “June,” and he was billed as June Alexander on the label.

• Dan Penn’s small custom acoustic guitar, which he called the “Car Guitar” because he could easily play it while riding in a car. His name is inlaid on the headstock with the letter “N” above that and a red heart engraved into the guitar’s heel.

• The framed original 1966 manuscript for “Out of Left Field,” written by Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham and later recorded by Percy Sledge. The lyrics were handwritten on a paper bag.

• Candi Staton’s leather buckskin jacket with double-button front closure and buckskin fringe and feathers made by Garma’s Exclusive Leathercraft and worn in the 1970s.

• A Wurlitzer electric piano used by Barry Beckett on sessions at Muscle Shoals Sound.

• David Hood’s Fender Precision Bass guitar with a multicolor woven strap that he’s used on sessions from the 1960s to the present.

The Apollo baby grand piano played by Aretha Franklin and others in recording sessions at FAME Recording Studios

Low Rhythm Rising. What does the exhibit’s subtitle mean?

“We wanted to get ‘rhythm’ in the title because so much is made of the rhythm sections there,” says co-curator Gray. “The Muscle Shoals sound tends to be simple and earthy — they let things simmer a bit before bringing a song to a boil.”

“The dynamic down there was why people were coming to get that thing, that low powerful rhythm,” adds Denney.

Beckett, who moved to Nashville in 1982 to become country A&R director for Warner Bros., explained the secret of the Muscle Shoals rhythm to author Barney Hoskyns in a 1985 interview.

“The Muscle Shoals feel came from layin’ back behind the beat a little bit,” Beckett said. “Nashville would play right on the beat, but if you divide your beat up into increments, say a hundred increments to a beat, and you lay back the bass drum, say two increments, and the backbeat, say, four increments, it doesn’t mean you’re playing out of time, it means you’re playin’ on the backside of the beat.”

Muscle Shoals: Low Rhythm Rising Opening Weekend Festivities

The more-than-two-year run of Muscle Shoals: Low Rhythm Rising kicks off this weekend with a series of events celebrating — and in many cases, featuring — musicians and music businesspeople presented in the exhibit.

7:30 p.m. Friday, Nov. 14, at CMA Theater: Opening Concert Celebration

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum will kick off the exhibit’s opening weekend with an all-star concert featuring Bettye LaVette, Spooner Oldham, Dan Penn, John Paul White and others backed by a house band of Muscle Shoals session aces.

Noon Saturday, Nov. 15, at Ford Theater: Songwriter Session With Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham

Penn and Oldham first met in Muscle Shoals in the late 1950s. Together and individually, they have written a slew of hit songs including Aretha Franklin’s “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man,” James and Bobby Purify’s “I’m Your Puppet,” James Carr’s “Dark End of the Street” and The Box Tops’ “Cry Like a Baby.”

2:30 p.m. Saturday, Nov. 15, at Ford Theater: Panel Discussion: Making Music in Muscle Shoals With Linda Hall, Clayton Ivey and Candi Staton

Hall, Ivey and Staton will discuss making records in Muscle Shoals. Hall was married to FAME Studio founder Rick Hall and still co-owns the studio. Ivey played keyboards on sessions at FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound before founding Wishbone Recording Studio. Staton cut a string of classic country-soul records in Muscles Shoals, which earned her the title “The First Lady of Southern Soul.”

1 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 16, at Ford Theater: Musician Spotlight with Mac McAnally

A longtime member of Jimmy Buffett’s Coral Reefer Band, producer, musician and songwriter McAnally went to Muscle Shoals as a teenager in the 1970s, made his first recording as a studio musician at Wishbone, and also played on sessions at FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound. His songs have been recorded by an array of artists, including Sawyer Brown, Kenny Chesney, Alabama, David Allan Coe and Charley Pride.

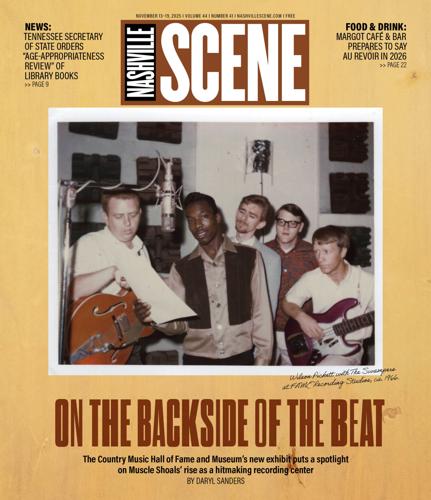

Wilson Pickett with The Swampers at FAME Recording Studios, ca. 1966.