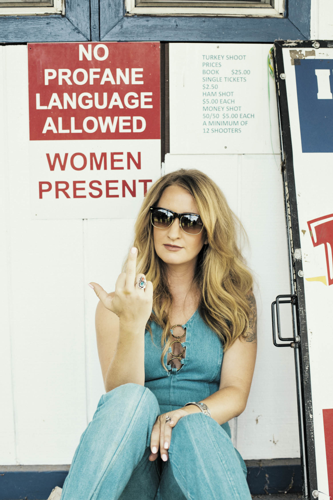

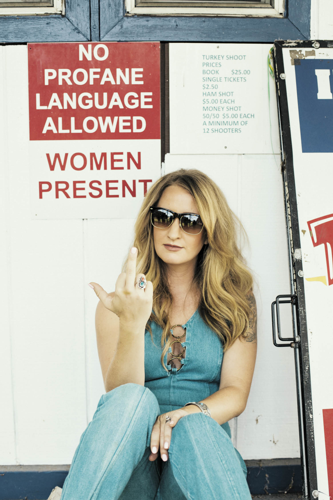

Margo Price at American Legion Post 82

They say “break a leg,” but Margo Price almost broke a finger, accidentally slamming it in a car door and spraining it before one of many random, unexpected recent gigs: opening for Eric Church and Kid Rock at the East Carolina Pirates’ football stadium in Greenville, N.C. And that’s OK — the singer’s used to pushing through hard knocks, and she knows better than to rely on good luck.

When the Scene sits down with Price in the empty veritable time machine that is East Nashville’s American Legion Post 82 on a hot August Monday afternoon two days after what was her first (and likely not last) stadium gig, things are going well. She’s about to fly across the pond for a string of dates in the U.K., before embarking on a U.S. tour that’ll see highlights including headlining a two-night stand at The Troubadour in L.A. and singing with Willie Nelson at Farm Aid. In July she sang “Me and Bobby McGee” with Kris Kristofferson at the Newport Folk Festival. Three months earlier she played Saturday Night Live.

And less than a month before that, she made history when her debut solo LP, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, entered Billboard’s Top Country Albums Chart at No. 10. It was the first time in the chart’s 52 years that a solo female artist had debuted in the Top 10.

But around this time last year, Price, now 33, had little cause to even dream so big. “I’d been kicked down so many times,” she says, “so I might as well fucking sing about the scumbags.” After 12 years grinding it out in Nashville’s trenches — dropping off gift baskets with beef jerky, liquor, dirty magazines and her CD at Lightning 100, or getting ripped off by a bloodsucking publicist who’d bill her without bothering to mail out CDs at all — the singer’s morale was at an all-time low. She’d shopped Daughter — a stunning trad-country set of songs about heartworn hardships like growing up the daughter of a foreclosed-on-farmer-turned-prison-guard in rural Illinois and taking lick after lick in Nashville — to labels up and down Music Row. They all passed.

In 2011, Price sent an unsolicited copy of her then-band Buffalo Clover’s second album Low Down Time to Jack White’s Third Man Records. “Everybody wanted to be on that label,” she recalls. “I sent in my record, and I sent in my vinyl in a box.” That didn’t work, but in 2015, the label was listening. Third Man’s Ben Swank had heard good word of mouth on Daughter, and by November the label had signed its first country singer for a two-album deal. And everything changed.

Almost everything.

Despite making the final round of voting (and releasing one of the most critically acclaimed country sleeper hits of the year), Price didn’t get any CMA Awards nominations this year. But she was named the Emerging Artist of the Year this week at the Americana Honors and Awards. And that’s a more fitting accolade, as Price remembers cutting Daughter at Sun Studio in Memphis with one simple goal in mind: getting it out before the AmericanaFest deadline, with modest hopes of getting a spot somewhere in the lineup.

There’s been a lot of firsts in the past year. [Laughs] A lot of things that I didn’t ever expect to be on the bucket list. Of course, things I wanted to do, but things I wasn’t expecting.

You spent so many years pounding the pavement trying to make something happen. Do you think that made you more prepared for things to start happening when they started happening? Yeah, completely. If I wouldn’t have had all those years in the trenches, there would be no way to be prepared for that. Even SNL, just performing live. Everyone asked me if I was nervous, but I wasn’t nervous. I think it’s just because I had full confidence in my musicians and me being able to execute the task at hand. If it would’ve happened seven years ago or 10 years ago, I probably would’ve made a fool out of myself in a lot of situations.

When you were recording this album, what were your goals in terms of getting it out at the time? Oddly enough, one of my goals was just to get it out before the AmericanaFest deadline. I’d attended the show several years prior and just really wanted to be involved, but I hadn’t put out a record in a minute. … I didn’t set my goals much higher than that. I just wanted to be mid-level and then stop. I’d be happy if I could just sell out theaters. I don’t aspire to be, like, an arena act.

In the Americana world now there’s this thing where country has this indie-cool factor. Yeah. Making country cool again.

The New York Times Magazine mentioned how at a show of yours in Brooklyn, there were people coming from their jobs at Vice Media and Kickstarter — these very, like, new-school tech professionals. Right. People who are maybe just appreciating country music for the first time.

Do you remember what it was like doing this type of music before that? Yeah. It wasn’t cool at all. And I’ve been playing these songs for a long time. It’s funny how that changes. I didn’t have to change much of what I was doing. Then all of a sudden, I just kind of fit into this niche. But I mean, of course I see somebody like Chris Stapleton up there at the CMA Awards and I’m like, “I would like that.” … But I still feel much more comfortable hanging out with the rock ’n’ roll and indie crowd.

Is there an aspiration to get on country radio and penetrate that world? Well, that hasn’t really been my idea. But, you know, the folks behind me, it’s like why shouldn’t country music be on country radio? It makes perfect sense.

It’s a strange thing that that’s the battle. It’s like you have to cross over into country music now. Some of the stations are picking up my music, and some of them are very receptive. Especially, say, folks in Los Angeles and certain stations. But some of them are completely perplexed when I go in there and play for them. It can be painful. I’m like, “What kind of music is on your station?” Then they tell me the names — and I’ll protect the innocent here by not saying them — but I’m like, “You’re not gonna like what I do, and I’m probably wasting my time by coming out here and shaking your hand and giving you my album.” But I’m remaining hopeful.

Some of the themes on the record, especially when you’re talking about your family on the farm and your father working as a prison guard, those themes seem like they might be more relatable to a country radio crowd, or more populist crowd than they might to “hip” country and indie-rock fans. I guess maybe there’s a bit of an irony there. Yeah, I still feel like I don’t know where I’m fitting in.

Some of that stuff is all kind of a part of outlaw country folklore — divorce, jail, drinking whiskey and vice. Do you get the sense that people in the more erudite indie world like to hear about those themes? Like almost a fetishization of seeing a window into something else? Or is it because you’re putting it in the context of a modern world? I don’t know if it’s the irony of it, but those themes still come across to everybody, because everybody has parents that have been divorced, and America has such a problem with drinking. Those things will never go away from our culture. But that being said, I’m really excited for putting out the next album and for touching on broader themes such as the pay gap, the trouble with police and guns, and things that are a little scary to talk about.

So you’re going in the direction of more explicitly political? Yeah, I want to touch on that more. With the farming crisis and pesticides and all these things Neil Young talks about, but nobody even listens to half the time — it is important. It’s messed up that nothing can be done about it. Back in the ’60s and ’70s, people wrote topical songs, and it spurred change and all these great things. Now are we so apathetic and drowning in our phones and technology that we don’t even care? But I still will talk about things that are very close and personal to me.

Before you signed to Third Man, had you gone to a lot of labels? Music Row labels? I went to everybody. It was insane.

What was the kind of feedback they’d give you? I think people were really interested with the way things had started to turn with Jason Isbell and Sturgill [Simpson]. They always would want to see me, and they would always want to hear it. But then immediately when they heard it, they would want to change it or change the image.

I remember this one label — actually it was the only other label I got a contract offered with, and they were out of Memphis. I thought, “This is great! It’s not attached to Nashville.” It was a bigger chunk of money than I’d ever seen. They said they wanted to take off all the walking bass lines and take off all the fiddles. They wanted to make it more like a soul and rock ’n’ roll thing. I thought, “Where the hell were you?” I was just in a band that was doing that [Buffalo Clover], and it didn’t work. I’m troubleshooting, and this is what I need to do.

Another label I went up and played — a huge label in Nashville — I went upstairs and I brought ... Luke Schneider and Kristen Weber. He played dobro, and she played fiddle. I sat down and I got done, and they said, “It’s just so cute. You’re so cute ’cause you’re like singing like old-timey country music, but you’re not a hillbilly.” They just didn’t quite understand. I’d sent them the whole record, and they said, “Well we want to hear more songs. What other songs do you have?” And I’m not waiting around; I’m not recording more. I knew they’d just want me to get back in the studio and probably have me re-record the entire album. They didn’t understand that we’d done it the proper way. I thought it sounded great. It got to be so depressing — all the no’s.

There was one, like, midsized, not even a label, just an artist-management, distribution place — I don’t think they listened at all. The guy sent me an email which I checked before I’d ever even gotten out of bed. Just laying in my bed on my phone, and it’s just like, “We are aware of who Margo is, and we are not hearing it.” It wasn’t sugarcoated at all, the compliment sandwich where it’s like, “We really like this, but our roster just is too full.” It was just straight-up, “We know who she is, and we don’t like her.” So I went to the liquor store that day and got a bottle of mezcal tequila and didn’t stop till it was gone.

Does going through all that make the taste of victory even sweeter? Oh, totally! I remember when I was getting ready to sign, a friend of mine said, “A lot of toilets are going to be flushing when they wake up to see you signed to Third Man.” … It’s been nice to have that.

Was there ever a point or a moment where you thought about quitting? There were definitely points where I was drinking myself into such a stupor that subconsciously I was self-sabotaging. I don’t know, I think after I got that one email I was telling you about where I didn’t get out of bed, I thought, “If they’re not going to sign me than who the fuck is?” … I felt like if they weren’t going to do it and nobody else was, that I had exhausted every option.

What year was it? Let’s see. It was the summer right before last year’s AmericanaFest. … It was before I started talking to Third Man.

So things turned around kind of quickly. So fast. It was like April, May, beginning of June, I was thinking that nobody was going to put it out.

You didn’t think you’d be playing in a stadium? No, not a year later. I didn’t think I’d be, like, nominated for an Americana Award. It was crazy how when it does happen, it happens fast.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com