One day last fall, an empty Mason jar sat on Dan Rogers’ otherwise clean and orderly desk in his office at the Grand Ole Opry House. Turns out it wasn’t just any Mason jar. This one had recently been filled with pickled okra from Carrie Underwood. The megastar had grown the okra, canned it and given the jar to Rogers, who promptly ate it all. There were also blueberry and blackberry jams, also made by Underwood, sealed and awaiting a biscuit.

“This is the Opry for you,” Rogers says, attempting to explain the family feel of the internationally known live country music broadcast, which turns 100 years old this season.

Rogers would know. He’s been on the Opry staff for more than a quarter of its history, and for his entire professional career. In 1998, he started as an intern in the PR department. Now, as senior vice president and executive producer of the Grand Ole Opry, Rogers oversees everything that happens onstage and behind the scenes for the radio show. He sees the friendships that are fostered as part of what insiders say is a familial connection among Opry members and staff. Even so, some say the Opry needs to do more to reach out to marginalized communities — artists and audiences — if it is going to remain an icon in its next century.

What started as the modest WSM Barn Dance with fiddler Uncle Jimmy Thompson’s performance on Nov. 28, 1925, has become an international force, a long-running live radio show and a shaper of country music. Those three little words — Grand Ole Opry — have become synonymous with those other words most associated with Nashville: Music City U.S.A. History was written in 1927 when announcer George Hay followed a harmonica performance from DeFord Bailey by ad-libbing a line: “For the past hour, we have been listening to the music taken largely from the Grand Opera, but from now on, we will present the Grand Ole Opry.”

Neither the National Life & Accident Insurance Company (WSM Barn Dance’s original owner) nor the Opry invented country music. But after a century, the Opry has become integral to the genre. “It’s kind of like when something happens in your life, you call home to Mom,” Rogers says. “When something happens in your career, artists call home or come home to the Opry.”

Today, Ryman Hospitality Properties is the majority owner in the Opry, with NBCUniversal and investment company Atairos holding minority stakes. The group planned to celebrate the Opry’s 100 years with yearlong fanfare, but without changing its proven formula. A Grand Ole Opry show is structured in four 30-minute segments, with one artist acting as host, introducing the other artists. Typically, each artist plays just a few songs, and throughout the segments, the show hits many subgenres and relatives of country, from bluegrass to gospel, Western swing to Americana and contemporary hits. Today commercials are read live by announcers Bill Cody, Mike Terry and Kelly Sutton.

Grand opening of the Grand Ole Opry House, 1974

One recent Friday, Rogers wore a shirt that looked similar to the one he’d worn two days earlier and was called out by his staff.

“I was asked in a meeting, ‘You have gone home since Wednesday, right?’” he recalls. “I let it be known, I had gone home both nights. The shirts were both Imogene + Willie collabs, so they looked similar, but were not the same.”

It’s understandable that the Opry staff would be concerned that Rogers spent a night or more at the Opry House. Starting late last year, the Opry kicked off its centenary celebration with more frequent shows, more artist debuts on its stage and the publication of two books: 100 Years of Grand Ole Opry by Craig Shelburne — the first to list every Opry member and their contributions — and children’s book Howdy! Welcome to the Grand Ole Opry.

The celebrations amp up even more as the actual anniversary nears. The Opry broadcast from the Royal Albert Hall in London last month, and there will be seven shows per week (at minimum) every week in October. A goal of the centennial celebration was to have more shows than have ever taken place in one year — Rogers estimates the total number for this year will be 240. That includes more than 60 artists having their Opry debut, among them pop star Sabrina Carpenter, who is scheduled to appear next week, and onetime Beatle Ringo Starr, who played earlier this year.

Even as he has helped orchestrate the festivities, Rogers seems amazed at how the pace has changed from hayseed and hillbilly to livestream and Lainey Wilson.

“Nov. 28 is going to be just a banner night in the history of the Opry,” he says. “That is 100 years to the day that Uncle Jimmy Thompson sat down on WSM radio and played a fiddle tune that he could have never, ever dreamed would become the Grand Ole Opry, and that 100 years later, people from around the world would gather in Nashville to celebrate, and people from around the world would be able to tune in and watch. Think about trying to tell him: ‘One-hundred years from now, someone’s going to be sitting in Australia, and they’re going to watch this same show from wherever they are, and they’ll still be playing some of this music that you’re playing tonight.’ It’s pretty crazy.”

That has been the Opry’s role, to both preserve the music of the past, like that of Uncle Jimmy, and to promote new music. But the Opry’s trajectory has not been a straight line. There have been periods when ticket sales were slow and periods where the environment didn’t seem familial, such as a 2007 age-discrimination lawsuit filed by Stonewall Jackson. There were some periods when the Opry seemed more like a historical artifact than a hitmaker.

Johnny Cash makes his Opry debut at Ryman Auditorium on July 7, 1956

Part of what makes the Opry different from other music broadcasts is that members are inducted into the Opry. With that membership comes a commitment not just to play on the show’s stage — which famously features a circle of wood cut from the stage at the Ryman in 1974, when the show moved to the then-new Opry House — but to support its aims.

Singer-songwriter Ernest, a rising country star known by his mononym, says playing the Opry is not like playing other stages. First of all, he says, the Opry runs like clockwork: “You check into the green room, and you know exactly the time, down to the minute, that you are expected onstage.” But it’s different too, in that it feels like a responsibility to have a good show there. “It is not what the Opry can do for you, but what you can do for the Opry.”

Not all artists who play the stage are members of the show, but there is indeed some obligation that comes with Opry membership. Current members must nominate prospective inductees. The criteria for final selection into membership aren’t public; a group of Opry managers chooses successful country acts who can make a commitment to play the show, who have rapport with other Opry members and who demonstrate talent that will bring in audiences. Members are added throughout the year, unlike a Hall of Fame class, and there’s no publicly set number of members to be added annually.

Neither George Strait nor Willie Nelson is a member, because they didn’t want to commit to playing the hallowed stage with regularity. Hank Williams became a member of the Opry in 1949, but in 1952 he was fired due to repeated missed appearances. The hope was this action might serve as a wake-up call, but Williams died just five months later. There have been various “reinstate Hank” campaigns over the years, including one led by his grandson, musician Hank Williams III. But Opry membership is only for living artists who can participate in putting on the live show, so Williams was not reinstated posthumously.

Emmylou Harris, who has been a member since 1992, inducted Steve Earle last month.

Steve Earle performs at the Grand Ole Opry, September 2025

“When I was growing up, [the Opry] was the biggest thing that you could do in country music, without a doubt,” says Earle. Seventy years old at the time of his induction, he sees his membership at this stage of his career as part of his legacy, and he lists it alongside other highlights of his life and career — including his “Copperhead Road” being named the 11th official state song of Tennessee.

“There was no difference to me between that and The Beatles,” says Earle. “I heard The Beatles in 1964 when everybody else did, and I went to the Opry for the first time in 1962, and I saw Bill Monroe for the first time. I’m never going to be in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. I’m never going to be in the Country Music Hall of Fame. I’ve got three Grammys, and that’s probably all I’ll ever win.”

To remain relevant, the Opry must continue to attract new audiences. The number of people who grew up like Earle, listening to the Opry around a radio with their parents, is dwindling as the ways people listen to music becomes more fragmented and on-demand. While the Opry has made efforts to reach out to new and diverse artists to play its stage, those efforts are not without critics. DeFord Bailey, the Black harmonica player who helped launch the Opry’s popularity, played for decades but wasn’t paid copyright fees owed to him. Darius Rucker and the late Charley Pride are among the few performers of color who are members of the Opry. Other frequent performers include women of color such as Mickey Guyton, but they have not yet been invited to become members.

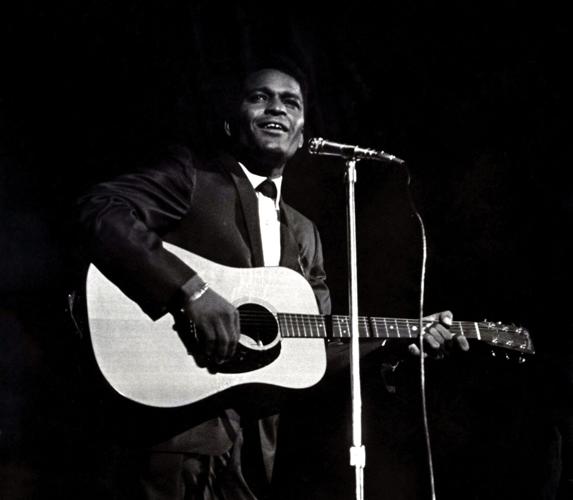

Charley Pride makes his Opry debut on Jan. 7, 1967

“I think the Opry needs to untether itself from country radio when it comes to its younger inductees — even though it might think those strings aren’t there,” says Marissa Moss, journalist and author of Her Country: How the Women of Country Music Become the Success Story They Were Never Supposed to Be. “Why [does] the idea of Sierra Ferrell or Elizabeth Cook, who has played the Opry so many times I truly have lost count, being inducted seem far-fetched?”

Other shows, like the Black Opry Revue and Music City Roots — which soon heads to Harken Hall — were established to fill the voids left by the Opry.

“It’s really complicated,” says Holly G, who created the Black Opry collective in 2021 to give Black country and Americana artists a platform for their music. “It’s hard not to think of it as a very revered institution if you are a fan of country music at all. But you look at it from a more objective lens, it’s hard to support [the Opry] given the fact that they have not had a good track record with being inclusive.”

The Opry’s efforts to have more diverse artists onstage — diverse in terms of race, gender and sexuality — have been successful, Holly G notes, and those 60 new debuts in this centennial year may have helped with that. And Amber Anderson, who is a Black woman, recently nabbed an on-air role at WSM-AM. But when it comes to members of the Opry, Holly G notes, the institution is lagging. The secrecy of the membership criteria, she adds, makes it hard for people to work toward achieving it.

“When you will not outline what a benchmark is, how can people meet it and how can you be held accountable for something if you’re not being clear on what the requirements are?” she asks.

While the 4,372-seat Opry House regularly sells out, the audience is often made up of more visitors than locals. The Opry is one of the state’s leading tourist attractions, but many Nashvillians feel the music and experience aren’t geared toward them.

The Opry, Holly G notes, is not the only Nashville institution with a largely homogenous audience. If the Opry wants to be more diverse — as individuals who work there have told her, and as the past year’s efforts toward more debuts have demonstrated — then the organization needs to take action to make audience members of all kinds feel safe and welcome. “We don’t have Black executives working in country music,” says Holly G, “and so until that happens, nobody’s really going to be able to do better.”

In 2023, the Opry acquired an ownership share in Whiskey Riff, a country-music website with a conservative bent. “Them buying Whiskey Riff very much undermines efforts that they claim to be making to make things safer and more inclusive,” Holly G says.

Despite the challenges, the Opry continues to resonate for many, even across oceans.

Irish bluegrass band JigJam has played the Opry three times; the first time, they got a standing ovation, remembers Jamie McKeogh, the band’s lead singer. JigJam is recording a new album at the Southern Ground studio in Nashville, and the Nashville Predators’ Ryan O’Reilly even sings on the album.

“When we do go back to Ireland, people are very wowed by the idea that a couple of Irish lads actually ended up playing there,” McKeogh says.

Patsy Cline on the Opry stage in May 1962

When Dan Rogers was flying back from London earlier this year, he overheard a couple at the airport say they were headed to Nashville for a week, and they planned to see the Grand Ole Opry three times. “I just thought, ‘My gosh, you’re coming to Nashville for a week, and the Opry means so much to you, you’re coming to this show three times.’ It just made my day.”

As the couple boarded the plane, Rogers handed them his card. He was able to give them some special experiences while they were in town and also invited them to attend the Opry broadcast from the Royal Albert Hall. That London show sold out within minutes of tickets going on sale in May. Rogers hopes it will be the first of many international shows, not just a one-time centennial celebration.

Rogers himself doesn’t attend every single Opry show, but it’s pretty close — and not because he has to. He trusts his team members, who love the Opry as much as he does, but he wants to be there. Sometimes, he’ll listen to the show from his back deck at home, but then he thinks, “My God, why didn’t I just stay at the show?”

“I don’t want to miss something,” Rogers says. “I hate to miss an artist debut. If we feel strongly enough about them to have them on this stage, I’d love to be here for their first time here. So many staffers can be here and do that, but I don’t want to be the guy who missed Dan Wilson’s debut, or Post Malone’s debut. If we’re doing our job the best we possibly can, then you want to be here for all those moments and all the unexpected things that could happen.”