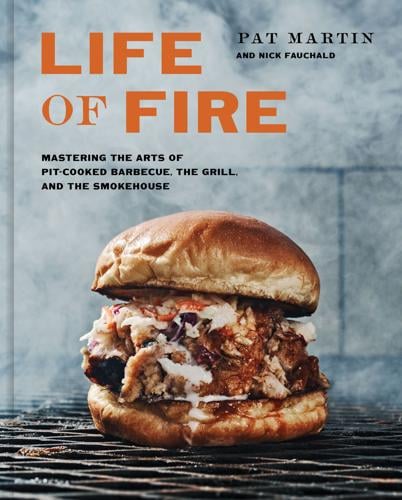

Pat Martin

Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint and Hugh Baby’s founder-owner Pat Martin wasn’t looking for a book deal when one was offered to him in 2016, but he did have clear ideas about what he would share with readers if given the chance. “I didn’t want it to be some cheesy Father’s Day release filled with recipes,” Martin tells the Scene. “If I was going to write one, I wanted it to be a teaching book that people would go back to again and again.”

The result of his efforts is Life of Fire, co-written with Nick Fauchald, and it’s more manifesto than traditional cookbook.

“Writing this book was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” says Martin. “It basically took up all my bandwidth for the past two years.” The entire project took more than five years to complete, beginning when the first photos were taken for the book. You can mark the passage of time by noticing how Martin’s three children grow up over the course of the photos, and how Martin has gotten a little grayer since Chapter 1.

The entire structure of the book revolves around various timelines, from Martin’s family roots in northeast Mississippi to his experiences first learning how to smoke meats while in college. He was under the tutelage of Harold Thomas, the proprietor of a barbecue restaurant in Henderson, a small West Tennessee town that was home to an astonishing half-dozen whole-hog barbecue joints.

Martin also tracks his professional journey, including working as a stock trader — a career that ended with an epic “Take This Job and Shove It” moment that he hints at in the book. (He might divulge the details about that moment around a late-night fire over a bottle of red wine after he’s known you for a while.) From there he progresses from opening his first 12-table restaurant in Nolensville to building the culinary empire that he oversees today.

The organizing timeline that parallels the fascinating personal stories in the book is the lifespan of a fire: birth, youth, middle age, the golden years, old age, cold smoke and after the fire. Each of these stages corresponds to specific steps of the open-fire cooking technique that Martin imparts through his easygoing writing style.

Martin doesn’t go out of his way to simplify his favorite cooking techniques for the average reader. On the contrary, he stays true to the methods he has developed and uses when he cooks for friends and family. “I didn’t even want to have a grilling chapter,” he says. “I wasn’t going to dumb shit down so that people could cook on a Weber. This is an arduous book! If you cook outside how I tell you to, you’re gonna screw up your yard, and you’ll need to call a welder to build some of this stuff.”

The grilling chapter ultimately became the longest section of Life of Fire — 60-plus pages. The chapter is a detailed dissertation on cooking open-pit barbecue using coals burned down from logs in a feeder fire or burn barrel and then shoveled onto the ground beneath a heavy, custom-fabricated steel grill. (Hence the burned-up yard and welder Martin was referring to.)

“Ironically, an open pit is the easiest place to start cooking over fire, but it’s the hardest to wrangle,” Martin explains. “Your flame is completely exposed to the atmosphere, and you have to constantly be preparing new coals and monitoring the heat. It’s the antithesis of ‘set-it-and-forget-it’ cooking.” The recipes and procedures in the “middle age” open-pit chapter are impressively detailed and conversational in style, but they should be approachable for anyone willing to dedicate time and attention to a half-day cook.

Though he never intended Life of Fire to be a Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint cookbook, Martin does share the recipes for some of the popular sauces and rubs he uses at his restaurants. But he does so solely because they are his creations and are integral to what he loves to cook, and thus necessary parts of his open-fire backyard cooking as well.

Grilled green beans with Memphis dry rub

Among the recipes and procedures in this chapter are some that every backyard pitmaster would love to learn more about. Spare ribs are Martin’s favorite thing to cook over an open pit, and his procedure is much more hands-on than the simplified recipes featured in many other popular barbecue books. Because of the open fire, Martin’s ribs require constant attention to burn down more coals to redistribute under the ribs, which must be flipped or rotated several times an hour over the course of a three-plus-hour cook. Martin promises they’re worth the effort.

Although he shares my disdain for baby back ribs as a waste of what could have made for perfectly good bone-in pork chops, Martin does share how he cooks them when he has to. Chicken thighs and whole chickens are also featured in the chapter, the latter accompanied by a recipe for Alabama white sauce. Vegetables don’t get the short shrift in Life of Fire — either grilled on the grate over an open fire, roasted in the embers and ashes alongside a protein or in foil packs that harken back to Cub Scout campouts Martin once enjoyed with his son.

But Martin saves his most passionate prose for the food that he loves best and has spent most of his adult life working to popularize and preserve — whole-hog barbecue cooked in a cinder-block pit. “I know whole hog sounds like ‘aspirational cooking,’ ” he admits. “But whole hog is within reach of most people as long as you’re willing to dedicate the time and be OK with occasionally screwing everything up and just ordering pizza for a big crowd.”

Martin’s description of how to cook a whole hog runs on for several pages, starting with sourcing a pig to purchasing the materials for building a pit to ordering wood and specific plans for stacking the cinder blocks. He even offers suggestions for what clothing to wear, what tools to have on hand and what to drink while cooking. (He prefers coffee, water, light beer and wine instead of whiskey because “cooking a hog is an endurance sport, and getting yourself or your crew hammered is gonna make it real hard to get to the finish line.”)

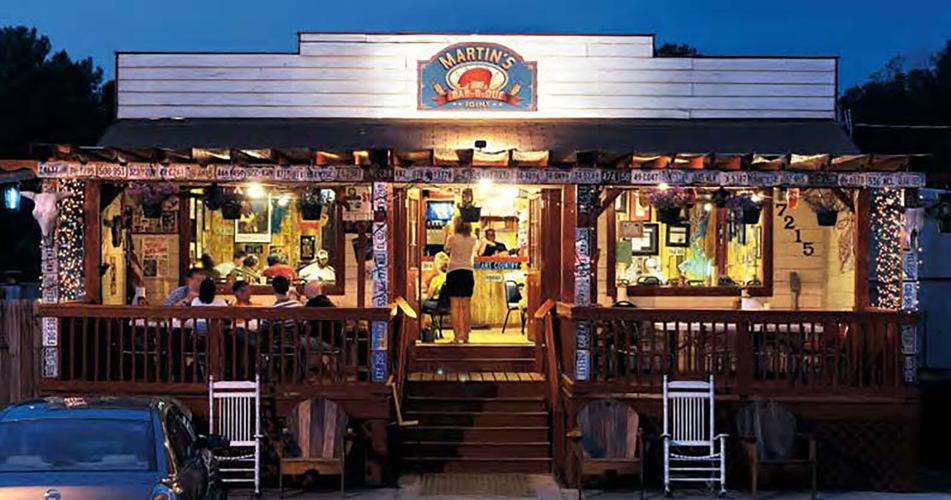

Martin’s Bar-B-Que Joint

“Whole hog is procedure-driven, so I had to figure out how to write it like I was there with you without being there,” Martin says. “Most books write up the whole-hog procedure like a recipe, but I can’t teach you this in one page. What I could do was to build a manual that will get you 85 percent of the way there. I had to work hard to figure out how to tell the reader what comes so natural to me, like how I don’t use thermometers and just hold my hand over the pit to tell if it’s too hot or too cool. I can’t tell you how my hand feels.”

Martin tested his final procedure by handing over his writeup to three friends who had never cooked a whole hog before.

”They cooked a pretty good pig,” he shares proudly. “We’ve all ruined hogs, even knowing better. But I truly believe that if you can cook this way, concentrating on whole animals and primal cuts, you can cook anything.”