Read also: "Patrons Reflect on Fido's Heyday."

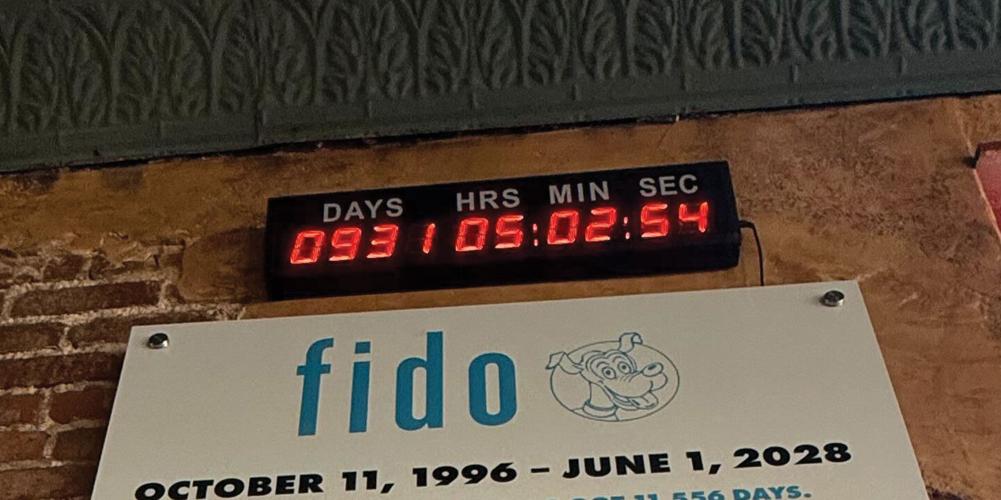

These days, when you walk into Fido from the 21st Avenue South entrance, you’ll see a Doomsday Clock-looking device hanging on the south wall, counting down to June 1, 2028. That’s the date Fido will be closing, at the end of its current lease extension. It’s more advance notice than restaurants typically give customers, staff or landlords.

“That clock is such a Bernstein sense of humor,” says architect Manuel Zeitlin, who worked on the Fido building design and is a longtime friend and supporter of Fido owner Bob Bernstein and his company, Bongo Roasting Co.

The countdown clock

As Zeitlin notes, Bernstein is known for his offbeat sense of humor and pranks. He’s also known as a guy who cares about coffee. In fact, Bernstein works from a table at Fido many days, “not as a needed person,” Bernstein tells the Scene, “but as a guy who wants coffee in the morning.”

That’s really how his whole business started. Bernstein was a guy who wanted coffee, or more specifically, coffeehouse culture, and in 1990s Nashville, there weren’t many options. He left a career in journalism and decided to open the kind of coffee shop he had studied at and hung out in while growing up in suburban Chicago. He originally dreamt of a Hillsboro Village location — the area was then a quirky collection of shops and small businesses with a neighborhood feel. He couldn’t find the right space, so in 1993, he instead opened Bongo Java on Belmont Boulevard, where it still welcomes coffee-seekers today.

Looking back at three decades’ worth of love connections, food and post-movie hangouts at the Hillsboro Village cafe

It was Bruce Dobie, former Scene editor-in-chief, who introduced Bernstein to his first investor in the early 1990s. Dobie and Bernstein met while both were young reporters in town (Dobie at the Nashville Banner, Bernstein at the Nashville Business Journal). Bernstein says it was always easier for him to find investors than to find physical space. (In that regard, maybe things haven’t changed all that much.)

Three years after opening Bongo Java, Bernstein was ready to expand and found a storefront available on 21st Avenue South in Hillsboro Village. He was planning to lease 1,200 square feet, but when the owners of Jones Pet Shop decided to retire, 3,600 square feet became available. Bernstein signed a 10-year lease. People told him he was crazy, he remembers, to sign such a long lease in that neighborhood. Now, 29 years later, people might question some of Bernstein’s decisions — but likely not the real estate ones. He renewed the Fido lease several times, and as it ends in 2028, Bernstein would have to pay the market rate to stay. He doesn’t know exactly what that number is, but knows it likely isn’t viable.

Over the years, Fido has expanded into other adjacent storefronts, totaling more than 5,000 square feet. The building is a century old, and in need of repair. (When Zeitlin and Bernstein originally designed Fido, they textured the walls to make them look old. No distressing would be necessary today.)

“I always call Bob a local hero,” says Zeitlin. “He stuck his neck out and took risks.”

The team named Fido as an homage to Jones Pet Shop, whose sign still hangs proudly over Hillsboro Village — and also in tribute (possibly tongue-in-cheek, given Bernstein’s sense of humor) to a mythical tale about the dog of the goatherder who is said to have discovered the magical properties of coffee beans.

Today the company also owns Bongo East (which has its own vibe and houses the Game Point Cafe), the original Bongo Java on Belmont and the Bongo roasting facility; the company owns the real estate for all those properties. They license the Bongo Java name inside the Omni Nashville Hotel downtown and at Nashville International Airport. Bongo operates Grins Vegetarian Cafe on the Vanderbilt University campus, but does not own that real estate.

None of the Bongo Java properties are exactly alike.

“I always kind of pictured [Fido] as Bongo Sr.,” Bernstein says. “It was like it was the little-more-grown-up Bongo, because I was a little older.” As a result, Fido won’t live on in any of the other locations. The Game Point retail store next to Fido is part of the same lease, so it will also close in three years. Bernstein hopes that retail outpost can be relocated elsewhere.

Bob Bernstein

For Nashville, Fido is more than just another beloved coffee shop that people are sorry to see go — it’s more than just another sign of Old Nashville giving way to New Nashville. It’s the end of an institution that helped shape the city’s neighborhoods and culinary scene. In the 1990s — first with Sunset Grill and then Fido — Hillsboro Village experienced a resurgence. It was the place to find independent restaurants; institutions like the Villager Tavern, the Belcourt Theatre and Pancake Pantry; and retailers like Bookman/Bookwoman, Davis Cookware and Pangaea.

Hunter Claire Rogers, a Nashville native and head of membership and communications at Soho House Nashville, remembers those days. When she worked at since-shuttered retail shop Fire Finch, she stopped at Fido for a bagel and coffee each morning — Fido offered a discount to employees of other businesses in Hillsboro Village. She remembers hanging out at Fido, both as a University School of Nashville student and later when it served as a reunion spot for friends returning home for the holidays.

Bernstein looks back fondly on those days. With lots of other locally owned businesses, the neighborhood would sponsor Halloween events for kids to trick-or-treat from storefront to storefront. Those sorts of things are harder to do, he says, when many of his neighboring businesses are corporate-owned.

Bongo and Fido launched the careers of many folks who have shaped Nashville’s culinary scene, including John Stephenson of the now-shuttered Hathorne and Andy Mumma of Barista Parlor (which now has a location in Hillsboro Village too). The coffeehouse has been seminal to Hillsboro Village and to the city. Musicians and songwriters tell stories of writing songs at Fido’s tables. Many people have stories about Fido being the first place they ate when they moved to town — more than a few tell the Scene it was initially because Fido was open seven days a week in a town that used to have few restaurant options on Sundays. Countless couples met there, had first dates there. One such couple still plans to have their wedding at Fido in 2026 before the lights are turned off, Bernstein says.

Bob Bernstein getting a cup of coffee at Fido

For all of Fido’s and Bongo’s strengths, there have of course been missteps.

Until the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Fido was open until 10 p.m., and it was the place to hang out and grab a bite after a movie at the Belcourt. When businesses reopened post-pandemic, Fido just couldn’t sustain night hours, Bernstein says. At first, that was partly due to staffing, but more so, the restaurant could not generate the revenue to stay open late. (Current hours are 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily.)

“It just doesn’t work anymore,” Bernstein says. “We would need to get more alcohol. We would need to change the whole menu. We need to maybe do some other things, and it’s like, how do you teach the old dog new tricks?”

In 2015, Hot & Cold — the Bernstein-owned ice cream and paletas shop in the space now home to the Game Point retail store — announced it would no longer carry Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams because Jeni’s was planning a scoop shop across the street. Hot & Cold was the brainchild of Bernstein and his wife Irma Paz Bernstein, owner of the beloved Las Paletas. While some small business owners might make that decision behind the scenes, Bernstein posted a sign on the door, and customers still have opinions today about whether that concern about competition was warranted. (Jeni’s has a number of locations in the city, including that one on 21st Avenue South.)

In 2018, Bernstein opened a coffee shop on Jefferson Street first called The Sit-In, and later called Jefferson Street Cafe. There was backlash about using the sit-in name, which Bernstein considered an honor to those who fought in Nashville’s civil rights movement. “That was lessons learned and an expensive story to tell,” Bernstein says of the restaurant, which is now closed. “The most disappointing part is that people that totally backed me and thought it was a great idea and were so supportive and happy and excited about doing it, as soon as there was a controversy, they walked away and left me out to dry.”

The decision not to extend the Fido lease past 2028 comes as Bernstein looks at his own future. He’s 63 years old, and while he doesn’t run the day-to-day businesses at the cafes, he’s not sure how long he wants to keep up the long hours of a restaurateur. He has a succession plan for each of the other restaurants, should he decide to step back.

“I got married late in life at 43,” he says. “My business was established and all that. Most entrepreneurs talk about how their family life suffers because of their business. Mine was the opposite. My business kind of stopped growing because I realized I’d rather stay home with my kids, and I was fortunate enough to be in a financial position and have the stores operating and have people in place that I could do that.”

Bernstein knows it’s unusual to give three years’ notice for a restaurant closing. He wanted to give customers a chance to come back and patronize an old favorite, and he has already seen former employees — and their grown children — come through. He also wanted to give employees notice, plenty of time to know they have a job, and time to think about what’s next. He knows this might make staffing tricky as they pursue other opportunities.

Since the announcement, Bernstein says he’s been creatively reenergized in a way he hasn’t been in years. That means he’s looking to resurrect fundraising dinners for causes that matter to him (largely education and the arts) and to focus on community building. When Bernstein and his brother Kenny (who was also essential in the building of Bongo, Fido and other projects around town) were kids, their mom used to create a “stuffed animal hospital” where she would stitch and repair their favorite stuffies. For about five years, Fido offered a similar event, and Bernstein hopes to revive that.

“I had so much excitement and fun opening this place,” he says, “I want to do the same thing closing.”