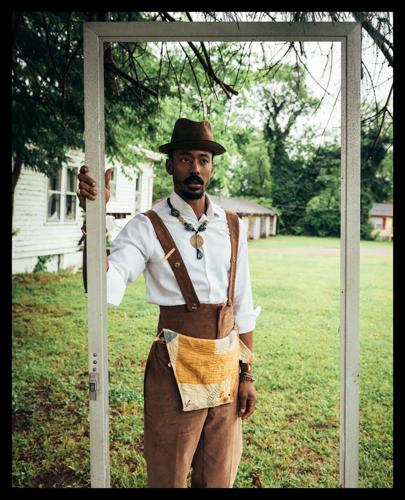

Carlos Partee’s family has lived in North Nashville for generations. He thought he knew plenty about his ancestors, but then he started looking through his family’s photo albums. His great-aunt, he learned, owned a beauty parlor on Jefferson Street, and her husband owned a shoe store right next door. He could relate to the people in the photos — aunts and uncles, cousins and grandparents — far more than he ever thought he could. He knew that these memories were important and at risk of being forgotten. He started thinking about the role of archiving a family’s — and a community’s — stories.

Partee founded the brand Cashville in 2016 to tell the forgotten stories of Nashville through media, events and merchandise. He also co-founded the popular Nashville Black Market. When he finally opened a brick-and-mortar location for Cashville, he knew he wanted to start with an exhibition of photography. The result is Faces of North Nashville, an exhibition of photography mounted in his space within 100 Taylor Art Collective.

“This exhibition is dealing with Black self-affirmation,” says Faces of North Nashville co-curator Michael Ewing, who worked with Partee to envision and execute the project. The curators have grouped photos in three archives that function a bit like a triptych — they are from different eras and sources, hinged together to make a whole.

Ruth Mcdowell

In the first, the Institutional Archive, the curators dug through images in Fisk University’s Special Collections to highlight Black businesses. Some of the businesses shown are still open, like R&R Liquor Store on Jefferson Street, while others have long since closed. Partee sees the Institutional Archive as an opportunity for his generation to see what is possible — the Black grocery store that sold fresh produce in what is now a food desert, the first Black firefighters in the area, the Black-owned dry cleaners. Partee says that people today may think, “Oh, you know, it's not possible — it hasn't been done before.”

R&R Drive-In Market

“But we can look at these photographs,” he says. “It's been done before.”

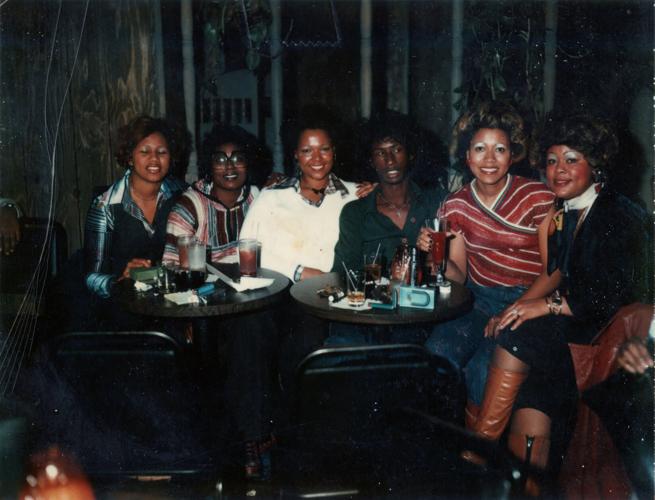

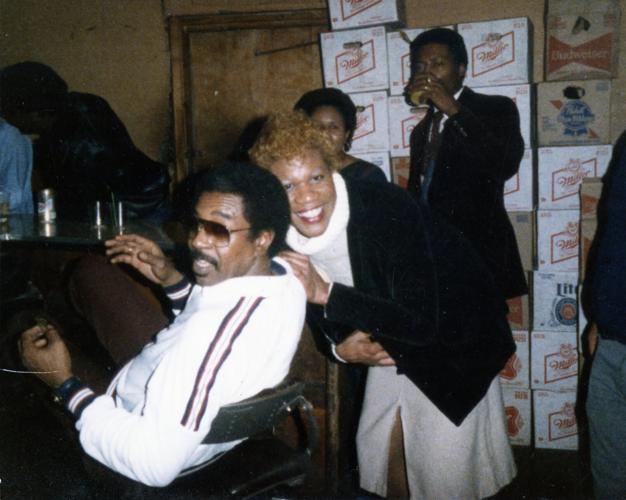

The second archive, the Family Archive, is personal to Partee and also central to the project’s vision. Ewing tells the Scene: “In coming up with this project, I was like, ‘[Carlos], we need to center your family in this, if we're going to tell the story about Nashville.’ I think one of the beautiful parts of being a curator is when you have the agency to embed yourself into the story, and it brings a kinship to it.” Like in the Institutional Archive, these photos show scenes from everyday life, but they are much more casual — snapshots of people with their arms around each other, joking around on bar stools, posing in their Sunday best.

Partee has found that, because he included his family, visitors to the exhibition gain a sense of trust in the project and want to to get involved as archivists themselves. Partee’s great-aunt and great-uncle owned a nightclub in North Nashville called the Beer Garden on 15th Avenue North, and some of the most compelling photos in the exhibition show his relatives kicking back and having fun, creating a sense of lightness in the gallery. The show’s most striking image is of Partee’s grandmother, Ruth Mcdowell, when she was a young woman. Like many of the subjects in the exhibition’s photos, Mcdowell looks self-possessed, empowered and spectacularly ordinary.

Billy and Hetha Dixon

Faces of North Nashville has given Ewing and Partee the opportunity to consider the work of curation and how that can be more accessible. “The word ‘curator’ only means one who maintains a collection,” Ewing says. Most families have them — the aunt who selects pictures for obituaries, the one who keeps track of birth certificates and records significant life events in the family Bible. “Part of it is taking away the hierarchy from this idea around the curator and understanding that the most important part of the collection is the collection of our memories,” says Ewing.

In the third archive, the Artist Archive, the curators have collected portraits by local photographers shot in recent years. They include work from Joseph Patrick II, keep3 and Andrew M. Rowlett II. Partee and Ewing didn't want to shoot anything new for this show. Rather, they wanted to “advocate [for] and to excavate things” that already exist, Ewing says. “In a world so obsessed with content — [how] Instagram and TikTok are all about creating new content, or creating new things — how do we re-engage the archives of things that already exist?”

The Lewis and Maclamore family and friends, 1960-1980

The exhibition closes on Feb. 28. It will then move to Robert Churchwell Elementary School, and Partee and Ewing will do a workshop related to archiving at East Nashville Magnet High School. The curators hope the show will continue to exhibit elsewhere in the future, growing along with the community and their stories. They want to encourage visitors to take the reins on their own family archives. “During the process,” Partee says, “we learned a whole lot more about how to archive photos better, how to teach other people to be archivists — putting on the white gloves and going in Fisk University was a really an eye-opener, especially from the curation standpoint of [telling other people], ‘You can do this, anybody can do this, anybody can tell the story of their family and their friends in the community as well.’”

Partee’s family archive has been digitized at Fisk and will now be part of the university’s Special Collections. Moving forward, Ewing and Partee plan to digitize the archives of more North Nashville families, “pushing people to go out into their communities and to their families and be the archivists in their family.”

W.A. Collier Dry Cleaning & Tailoring Co., 1728 Jefferson St.

“Once you leave from here,” says Partee, “you walk away, happy, joyful … [and think], ‘I'm gonna go home, and I'm gonna start curating my own family collection.’ ”

To visit the exhibit, you can book an appointment here, or attend the 100 Taylor Arts Market at 4-9 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 18.