On a hot afternoon in September 1987, photographer Sally Mann watched from across the street as her son was struck by a car and knocked 40 feet along the road, left bleeding and semiconscious. In Mann's new book Hold Still: A Memoir With Pictures, released last week through Little, Brown and Co., she writes that this was the moment she asked herself what kind of photographer she wanted to be. Could she ever be the type of photographer who would reach for her camera to document her son in the middle of the road, bloody and perhaps dying? No, she decided. She would not.

Mann's son Emmett walked out of the hospital relatively unharmed just a few days later, and Mann began to build a series of work that would come to define her career, for better or for worse: the Family Pictures series featuring her three intense, cherubic children posed in defiance of the world around them. She writes that she tried to exorcise the trauma of not knowing whether her son had been killed by following her own commandant to photograph what is important. "Photograph the great events of your life," she writes.

Hold Still dedicates only about 70 pages to Family Pictures, the series of her frequently naked children that resulted in accusations of child pornography and exploitation when they were published in the early '90s. But even through the contemporary veil of hypersensitivity to sexual trauma and myriad Internet trigger warnings, the images don't seem to hold the same damning subtext so many read into them when they first appeared. Still, and perhaps understandably, Mann spends pages going through the process that began with seeing her son bloodied in the middle of the road and ended a month later with the first of the Family Pictures — a shot of Emmett waist-deep in a river by the family farm. Mann includes 10 unsuccessful attempts as well as the final published shot, taking the reader through her long, arduous process along the way, as if in defense of the idea that she'd posed her children for any reason other than to create a beatific image — "In this one he's too far out of the water." ... "Here there's too much light on the trees behind him." ... "Off-center here and don't like those clouds." The inclusion of not only her greatest photographs but of the ones left on the cutting room floor provides a deeper insight into the mind of one of the world's most esteemed photographers, and makes the book required reading for even the most casual photography enthusiast.

For all her accolades as a visual artist, it might surprise you to know that Mann is also a hell of a writer. She begins Hold Still by confidently featuring journal entries she wrote as a teenager. They're written in a smart, observant style, but she nevertheless includes a self-effacing note: "It's a safe bet I was reading Hemingway that summer."

Early on in the book, Mann tells a story that's so dark and gripping it could easily have been the bones of a pulpy thriller — her husband Larry's mother (who Mann describes as a "ring-tailed yard bitch" in one of the book's first descriptions) killed her husband and then herself, leaving behind a mysterious crime scene and a closet full of prescription drugs. Mann baits the reader — you already kind of hate this woman for promising the newlywed Manns a new car, and then reneging and leaving them in financial peril. Even still, you might not be prepared for Mann's frank, unflinching description of the crime itself: "After we had been married seven years, late on the night of July 21, 1977, Larry's mother rose from bed and stepped over her underwear lying on the floor, its crusty yellow crotch facing upwards."

It's a disturbing, unyielding scene as grimly detailed as some of Mann's own photographs. But she goes on, never wavering, giving the reader a taste of the kind of unrelenting storytelling they are in for:

She walked to the closet across the room and pulled out a Stevens single-barrel 410 shotgun and a box of shells. Returning to her side of the bed, she sat next to her husband, who was covered up to his chin with a light summer blanket, sleeping on his back, his left foot casually crossed over his right. Breaking open the gun, she loaded one shell and clicked shut the breech. Then she pressed the muzzle tight against the back of his head between the ear and the midline and blew his brains out the other side.

Mann closes Hold Still with another description of a suicide, although this one is diametrically opposed to the story of her in-laws: In 1988, her beloved father killed himself by overdosing on the barbiturate Seconal. He didn't die right away — the pills were so old that they'd lost their effectiveness, and it took him hours to finally move from coma to death. Stuck to the bottom of the bottle was one last psychedelic orange pill. "I have it still," Mann writes, just above the photograph of her father as they found him, still alive but just barely, on the family couch. He wrote two different suicide notes, and Mann includes facsimile copies of both, dissecting each with her trademark gothic relentlessness. "There is something strange about the two," she writes. "The second, in a shaky hand and in crayon, for Chrissake, was written, I am quite sure, after he'd swallowed the last bright orange pill, or the last but one."

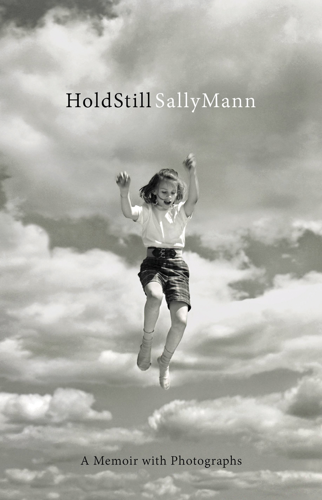

If you were to come across Hold Still on the bookshelves, you might see the author's name and the black-and-white photograph of a young girl on its cover and assume it's a collection of Mann's photographs. That's understandable — Mann is among a handful of contemporary photographers who could be considered famous, and she attained much of that fame for the black-and-white images she took of her young children. But Hold Still is more than just photographs, although there are plenty in here, including chapters on her series of dead and decaying corpses at the University of Tennessee's "Body Farm" and a series of her husband's naked body as it becomes atrophied from muscular dystrophy. But more than that, it's almost 500 pages of stories, letters, journal entries, family photographs and advice, and Mann is always the central subject — the cover photo is Mann as a young girl jumping in midair, the shot taken by her father.

Email arts@nashvillescene.com