When asked how he would like to be remembered, Jeff Buckley once said, “As a good friend. I don't really need to be remembered. I hope the music's remembered.”

Buckley released his sole full-length studio album Grace two years before his death by accidental drowning in Memphis in 1997 — and it is no doubt immortalized in rock history. But it's hard to say whether Buckley's music is truly the first thing he's remembered for, or if for most people, his name first conjures memories of the tragic end of a star who'd just begun his ascent. In the bedrooms of indie-rock fans across the world, Buckley is forever the 30-year-old man with soft eyes, gaunt cheeks and a mop of dark hair. The perfect tragic heartthrob. Add a four-octave range — a soulful voice that sounds like it’s a conduit for the heavens — and you have a cult legend.

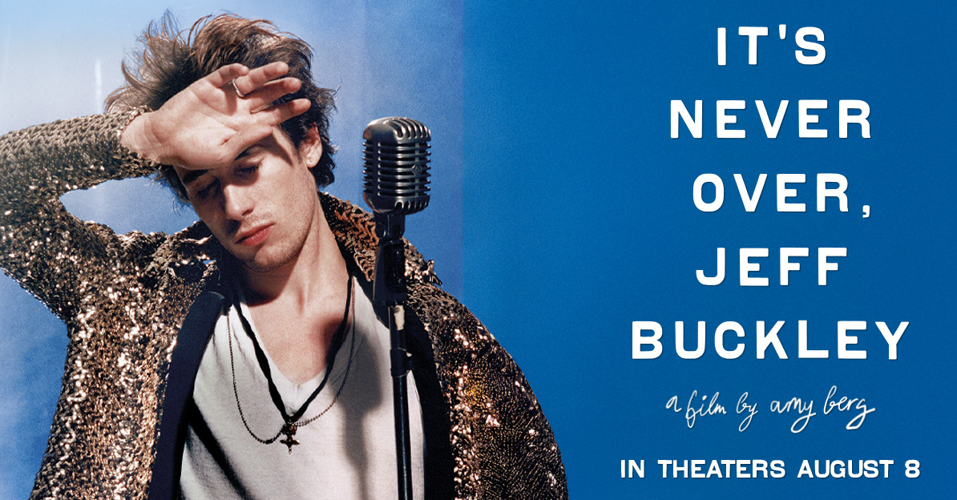

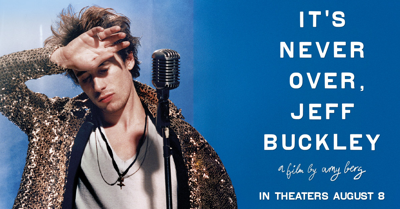

Director Amy Berg memorializes the gone-too-soon talent in her new documentary It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley, which opens a brief run at the Belcourt Friday. Stacy Goldate, the film’s editor — who also directed Lucy Barks, a documentary following legendary Nashville record store Lucy’s in its ’90s punk heyday — recently spoke with the Scene about editing the film, falling in love with Jeff Buckley, and how her days in Nashville’s music circles shaped her trajectory as a filmmaker. Goldate will participate in a pre-screening discussion before the film at the Belcourt on Monday, Aug. 11.

Jeff Buckley is someone whose music and mythos have such a devoted following. As the film's editor, how did you balance giving credence to him as a person and also this legend that’s been built around him after his death?

This is a film of someone larger than life, with such a passionate fan base. He’s a musician’s musician, a singer’s singer, a guitarist’s guitarist. When you’re making a film about someone so loved, who died so young, there are so many questions about him. As a filmmaker, you can’t have the audience in your head the whole time you’re working or you’ll get stuck.

For this film, I was the viewer trying to understand my relationship with Jeff Buckley. I wasn’t a devoted fan before the project — I don’t know how we missed each other, because we were close in age, and I was a DJ at WRVU, Vanderbilt’s college radio station, when his music came out. We listened to a lot of the same music.

Strangely, I wasn’t obsessed with his music. Coming into the edit, I had fresh eyes, and I fell in love with him on my own. That happened by listening to him talking in his own words through the archival material.

When you’re making a music documentary about someone who died young and had an unfinished legacy, how do you know when the edit is done?

The director, Amy Berg, is ultimately the one who decides when it’s done. I can’t speak for her, but for a passionate filmmaker like her, it's almost never done. Even after the film was finished, more footage appeared at her doorstep, which will play after the screening.

For me, it was about feeling like I’d had a full experience watching the film and making sure no gems were left on the floor. I combed through archival footage at the last minute and found things I loved. We were lucky. His mother saved so much, including phone calls and voicemail messages. It was an editor’s dream.

Is there one moment in the film you’re especially proud of cutting together?

There are so many. One of the most challenging was his performance at Sin-é, where he was discovered in New York City. That scene was a real collaboration between [co-editor] Brian Kates and me. We were trying to make viewers feel as if they were in the room experiencing Jeff Buckley for the first time. You’re in a tiny club, an espresso machine in the background, and there’s this incredible voice right in front of you.

You got your start making documentaries about music, directing Lucy Barks. Is there anything you learned making that first film that you’ve carried with you?

Everything. I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for Lucy’s Record Shop, Lucy Barks and WRVU. Those were imprinting experiences, and many of the people I worked with then are still in Nashville. I think of Chris Davis, one of my best friends from Vanderbilt. He’s in a band called The Cherry Blossoms.

In the ’90s, before social media and YouTube, the only way to learn about music was through MTV, or if you were lucky enough to have a local club or a college radio station. Chris always said, “When you like somebody’s music, look at the liner notes. Look at who they collaborate with and look and see if they thank anyone.”

In Grace, when Jeff sings “Hallelujah,” he dedicates it to Leonard Cohen, Nina Simone and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Listening to Jeff could lead you to discover them. Much of how we learned about music back then was word-of-mouth and what other people were listening to. Lucy’s helped me understand that, and the generosity of Donnie Kendall, April Kendall and Mary Mancini opened the doors for me to be there. My film school was filming at Lucy’s every weekend for a year.

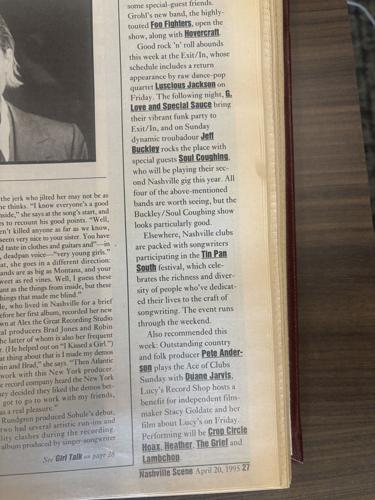

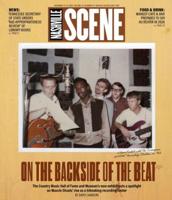

A 1995 Nashville Scene show-preview feature including a Jeff Buckley performance alongside a Lucy's listing

I even have a Jeff Buckley thought around Lucy’s. I was getting ready to go to Nashville and pulled out an old press packet clipping I had saved from a benefit concert at Lucy’s for the film with Lambchop, Crop Circle Hoax, Heather and The Grief. The Nashville Scene featured it in the calendar. It was 1995, and Grace had just come out. Well, guess what was also recommended that same weekend with a big photo — Jeff Buckley’s one and only Nashville show at Exit/In that same weekend.

I would do anything to know if he might have wanted to see Lambchop, since they had slide guitar — something he loved. I'm sure he was busy and might have even been in another city that night. But one can only fantasize. Jeff and I were kind of like ships passing in the night, so close to his orbit.

Do you have a favorite Jeff Buckley song?

I love “Mojo Pin.” I love the way he can move through sound, and there’s a universe of emotion in his voice, even without words, and his songwriting. That song, more than any, takes me somewhere else, and I loved working with it in the film. I also love “New Year’s Prayer.” The repetition of its mantra “feel no shame for what you are” helped me through the editing process.

A Jeff Buckley ad featured in a 1995 issue of the Nashville Scene