On Feb. 3, the Frist will open Jeffrey Gibson: The Body Electric, an expansive exhibition from the contemporary artist and MacArthur Fellow whose work is in collections from the Whitney Museum of American Art to the Smithsonian Institution. Gibson draws on his background — both as a Choctaw-Cherokee and a child of the 1970s — to inform his art-making practice, which is both playful and profound, vibrant and extraordinarily detailed. The Scene spoke with Gibson about the show’s title, his ideas about identity and the site-specific mural he’s planned for the Frist walls.

The exhibition is called The Body Electric, which is of course a phrase from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, but it also brings to mind the movie Fame. It’s such a great synthesis of associations — New York and queer history and transcendentalism. Can you talk about the inspiration you took from either Whitman or Fame or a combination of the two?

To be honest, I don’t think Whitman was really that much in my mind when I came up with the title. I turned 50 recently, and I had the realization that I’d been doing this for a while now. And I am very much a pop-cultural baby — that is where most of my interest lies, at least its beginning point. So I think a lot of it’s influenced by these past few years where, as a country and politically, it’s felt so divisive. I guess I just thought we would be in a different place, based on the times I grew up in. I was thinking about my childhood and I ended up watching Fame. It took me back to being a kid — realizing that if I wanted to be an artist, I had to go to New York, because that’s where I’ll be accepted and have freedom and support and community. So I just started listening to that song [“I Sing the Body Electric”], and I realized that it could be seen as kind of corny, but I also am always advocating for taking seriously the things that we might otherwise dismiss.

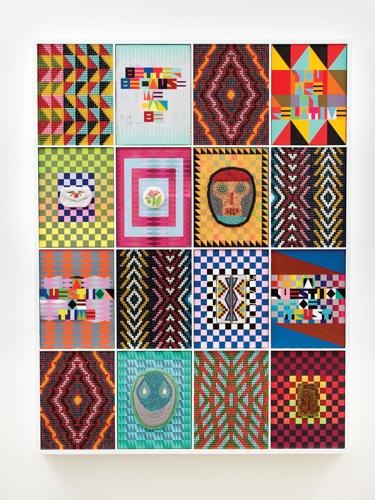

“War Is Not the Answer,” Jeffrey Gibson

It’s interesting that you grew up thinking you needed to be in New York to be an artist, but it seems like your practice has been able to take off since you moved your studio out of New York in 2012. I’ve seen a lot of artists who’ve left their New York studios, and feel extremely trepidatious about making that move, but then they begin making work in a larger studio space, and are no longer tethered to that tradition — New York art history, European art history. I’m interested to hear your thoughts about how that move has changed your practice.

I think I’ve been pretty public in the past about having moments when I’ve considered walking away from pursuing a career as an artist. After the last economic crash and how it impacted the art world, my husband [Rune Olsen], who is also an artist, and I had nothing going on for a few years. We ended up traveling. I lived in San Francisco and then France, and I was teaching in an art school on the west coast of France. I don’t know if we knew it at the time, but it was kind of a realization — I don’t think I want to live in a city where there’s so much choice and so few boundaries in certain ways. But there are also so many boundaries, mostly to do with financial costs of living there. I just realized that my brain was beginning to think about larger things in interesting ways. Even the conversation that can happen in New York among artists, I find can be so focused on the market and exhibitions and names. I just felt like, you know, I think it might be holding me back to have all these voices in my head.

I knew that I wanted a family, and I knew that I was ready to put down roots someplace and think about the future of who I wanted to be as an artist, and I just needed to quieten down all the voices that exist in the art world for artists. ... And this studio building [a former schoolhouse] certainly never would have happened in the city. It’s a huge shift in the context that I work in, and that has certainly found its way into the way that I think and work, in a positive way.

“Better Because We Can Be,” Jeffrey Gibson

While you identify as a Choctaw-Cherokee artist, which is something that I’m sure you’re proud of, you’ve said that, because understanding of the Native aesthetic is so limited, it creates a fetishization for you to perform to and for people to respond to. I think that’s smart and good for people to be aware of — that you can be proud of your identity and also not want to be marginalized for it.

I’ve had criticisms from all sides — people have said, “Why do you identify as a Native American artist? Isn’t that pigeonholing you?” And I feel like that comment is very much loaded with an acknowledgement that to claim your identity as being Native is kind of seen as less than not claiming a specific identity. And I think that also, we still refer to people that way. There are female artists, Jewish artists, Black artists. So if that’s where we’re at and I don’t claim this, then we don’t exist in that realm. I feel like I know that my hope in the future is that we will not necessarily only describe ourselves by our cultural backgrounds or by our skin color, but that’s where we’re at culturally.

One of the aspects of the exhibit is a site-specific mural. What are your plans for that?

I did the first wall painting or mural in 2016, and I don’t really remember how I arrived at it, but I think for a painter, there’s something thrilling about doing something that you know is not going to last forever. I had come back from the Sol LeWitt installation at MASS MoCA, and I spent a lot of time thinking about how great it was, how these kinds of wall-based pieces worked, and how they play around with ownership. That’s how it started. And there’s a lot more to talk about how the design came about, thinking about color, thinking about how the kind of elongated triangle shapes, layered up, could feel like landscape. So I get to think about things like horizon lines and sky and time and light. And the title [“THE LAND IS SPEAKING | ARE YOU LISTENING”] — that phrase is something I wrote.

Jeffrey Gibson

It’s interesting that you started these in 2016, which was a time a lot of people were thinking about a political shift and emotional shift in America. And to go to the walls, the mural’s history as protest art, to me that seems germane, even if it wasn’t top-of-mind.

It’s funny that you say that. I’m actually working on a larger project right now, and the murals have become a very significant part of it. I was thinking about all the murals that had happened in Indian boarding schools across the country that many people are unaware of, because those buildings were not valued, and many of them were demolished and they weren’t photographed. At the Santa Fe Indian School there were lots of them, and that building was torn down in the mid-2010s, and I remember there was no public discussion before it was demolished. It just happened one day. And you could see in the rubble the painted murals. So this is the first time that I’m thinking about it in the continuation of this history of murals made by Native people. Looking at everything from protest posters and pop culture — buttons and patches and stickers that people collect — all of that finds its way into the work.