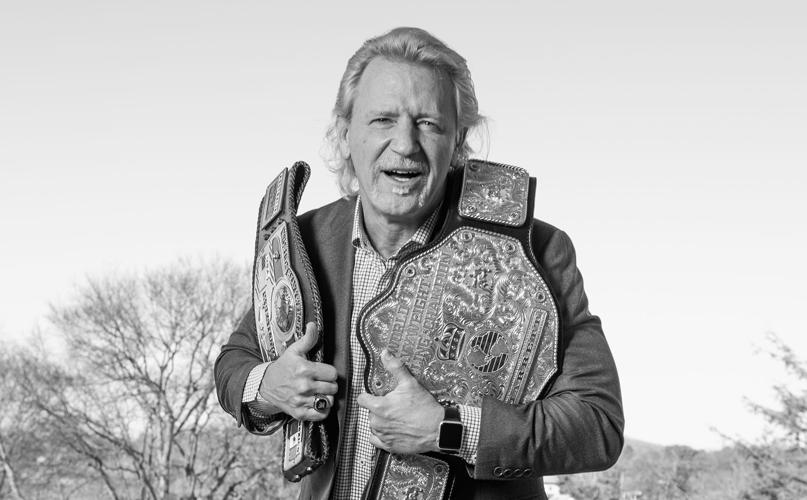

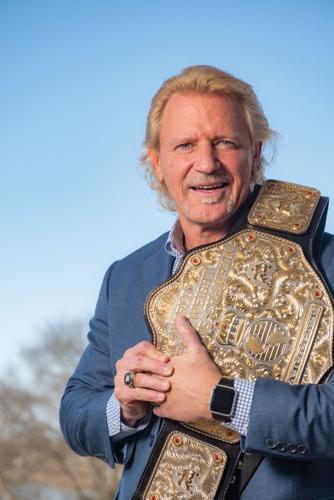

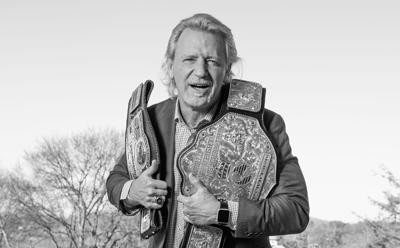

In January, Jeff Jarrett stood in New York City’s legendary Hammerstein Ballroom — just a stone’s throw from Madison Square Garden, the longtime cradle of his former employer WWE. A third-generation wrestler and promoter from Hendersonville, Jarrett has worked everywhere from churches to stadiums, from lucha shows in Mexico to historic wrestling halls in Japan. But this was his first appearance at the Hammerstein in a decades-long career. As Jarrett describes the evening — his first performance inside the ring since 2019 — the whole affair felt a little bit like a “paradox.”

It was one of the biggest nights for indie wrestling in a long time: the first wrestling show at the Hammerstein since 2019 and by far the biggest show ever for Game Changer Wrestling, a scrappy New Jersey-born outfit that over the past several years has transformed into a cult movement. Many now consider GCW the third-biggest wrestling promotion in the United States, behind WWE and All Elite Wrestling — and here, waiting in the wings, was an old-school cowboy and one of the last real connections to wrestling’s Southern past.

So many of the wrestling fans in the audience had grown up with Jarrett — whether they knew him as the curly-haired would-be country star Double J of 1990s WWF or “The Chosen One” of WCW, the more ruthless “King of the Mountain” in his own company TNA, or his brief turn as a youth pastor “jacked up on Jesus” in Harmony Korine’s 2012 movie Spring Breakers. For his return, he introduced an updated gimmick: “The Last Outlaw,” cloaked in black like a living Johnny Cash song, toting a guitar that just begged to be bashed over someone’s head. His opponent, on the other hand, seemed to embody the new school: Effy, an openly gay indie darling who walks out to “Goodbye, Yellow Brick Road” and brutalizes and flirts with his opponents in equal turn. Jarrett could feel the overpowering nostalgia from the moment he stepped into the ballroom, as the crowd roared with chants of “Double J” and “King of the Mountain.” But in Jarrett’s view, that night wasn’t all too different from wrestling’s past.

“GCW says they’re pioneers of what they call deathmatch wrestling, which back in the ’90s people called hardcore wrestling,” Jarrett tells the Scene. “However you describe it, we were really doing the same thing back in Memphis, taking the fight outside the ring and brawling in the concession stand or in the crowd. What they’re doing seems new, but it’s also old-school.”

After the bell rang, Jarrett unbuckled his leather belt and started to whip Effy, bringing that old-fashioned Southern strap-match flavor to the 21st century. There might be some deliberate homoeroticism to Effy’s gimmick, but his hard-brawling, full-bodied style of violence is as classic as rasslin’ gets.

“Paradoxical” is a pretty good word to describe Jarrett too, if not wrestling itself. In an industry so often dominated by nostalgia, Jarrett has constantly looked to the future. He’s got the good humor and easygoing charm of a Southern good old boy, but he speaks like a media mogul, effortlessly riffing on digital media and marketing strategies. Business is in his blood as much as wrestling.

Decades ago, Jarrett’s grandmother supported her children as a single mother selling tickets for wrestling shows at Nashville’s Hippodrome, working her way up through the ranks in an industry historically dominated by “the boys” to start promoting shows across the Mid-South. Her son Jerry, Jeff’s father, started slinging programs at wrestling shows at an early age, and would eventually found the legendary Memphis-based Continental Wrestling Association in 1977. CWA was home base for legends like Jerry Lawler, Jimmy Hart, Terry Funk and even Andy Kaufman — and it’s where Jeff got his start, first as a teenage referee, and then as a championship-winning wrestler with luscious blond locks.

In the 1990s, Jarrett became a television star with the WWF, where he wielded his guitar as a weapon, came to the ring with a “roadie” instead of an enforcer, and even performed a Clint Black-sound-alike single called “With My Baby Tonight.” After WWE solidified its wrestling monopoly in the early 2000s, Jeff and his father co-founded Total Nonstop Action Wrestling — mostly referred to by the provocative acronym TNA — which is now known as IMPACT Wrestling under different ownership. But the Nashville-based company wasn’t a vanity project for Jarrett. TNA was a training ground for so many wrestling icons, including future WWE superstars AJ Styles and Samoa Joe, as well as Tennessee’s own beer-swigging hellraiser James Storm. It provided the only real televised wrestling alternative to the Disney-fied WWE in the United States for more than a decade.

Though he’s no longer directly in the business of booking or promoting wrestling, Jarrett is keeping himself more than occupied with a number of new ventures. During the pandemic, he launched a storytelling podcast called My World, in which he spins fascinating yarns from his life on the road and opens up about his countless years at every level of the wrestling world. He’s also parlayed his years as a television and media executive into a new company called Moonsault Digital, which is investing in and developing digital wrestling collectibles and games — and which purchased the Springfield, Ill., minor-league baseball team the Springfield Lucky Horseshoes. Jarrett has seen firsthand the evolution and development of broadcast entertainment. He was there when wrestling was filmed in small TV studios; he was there during the cable boom years when Monday Night Raw & WCW Monday Nitrowere two of the biggest TV shows — period — and he was at the forefront of the transition to streaming. FITE TV is now the primary on-demand home for combat sports — Jarrett was the first person in wrestling to partner with them.

“When TV was first invented, wrestling was one of the first kinds of programming, because you can get a massive return for a relatively low cost,” he says. “Wrestling has grown exponentially because of streaming — you can dial up any promotion around the world, from Japan to Mexican lucha libre, and be connected at any time. The business is probably the healthiest it’s ever been.”

For as much as wrestling has radically changed, the heart of the medium is still the same for Double J. “Sting is still out there in his 60s, every week on AEW, and the emotional connection is still the same with the crowd that it was years ago,” Jarrett says. “The athletic move sets and the styles might change like they do in any sport or entertainment, but the basics in this industry of emotionally connecting with an audience will always be the same.”

Our profiles of some of Nashville’s most interesting people, from a sought-after local actor to a wrestling legend, a former Miss Tennessee and more