Jeremy Camp

Jeremy Thomas Camp is a Grammy-nominated contemporary Christian music artist. His first major label studio album, Stay (2002), earned him chart-topping recognition. Camp is also known for his rock aesthetic and physique.

I didn’t remember Jeremy Camp until my therapist assigned me that damn exercise for the third time: Go and write your ideal partner. My ideal partner?At that point, I’d lived in Nashville for five years, in Tennessee for nine, and white gay Nashville was a thing of silence to me. Tinder matches with no responses. Unanswered DMs — Hey, I really appreciate your vibe. I’d love to grab coffee, if you are game! And then of course, that wall of white, Greek torsos otherwise known as Grindr. (Greek, not for their ethnicity, but more for their silence — like Greek, ab-bearing statues of old.) None of this was ideal. Sorrow had turned to anger, and anger unexpressed had given way to rage.

Around the same time, I began writing a story called “All About Adam.” It was the only place I felt safe putting my rage. This was in a long tradition of Black gay men writing, painting, filming, poetizing their fury at finding themselves invisible in white gay communities. Reginald Shepherd’s 1991 essay “On Not Being White” is in this tradition. I wrote about a Black boy’s infatuation with his white classmate, Adam. But I found it difficult to write Adam, as his face belonged to the many men in Nashville who had looked above, around, behind me — never at me. Feeling dehumanized, I had decided to respond in kind, and so I’d eventually forgotten what their faces looked like. If I was going to bring the reader into the face of Adam, I needed a muse.

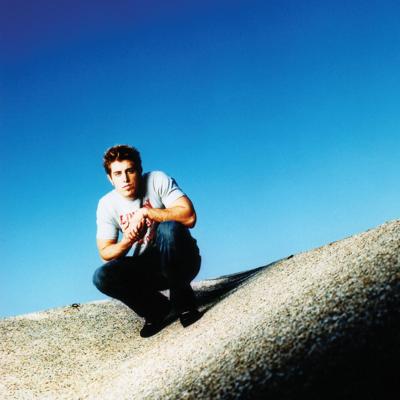

It was a simple Google search that opened all this shit back up. At first it was the features: chinstrap beard, spiky brown hair. And then a name from years before came to my mind: Jeremy Camp. For days on end, I looked at scores of Jeremy Camp photos, but I kept going back to one black-and-white image in which he sits, folded over, hands on knees. He gazes out with eyes that are warm and attentive. This became the face of my fictional Adam. But even after the story was sent to my agent, I found myself sweetly haunted by that gaze — because I had seen it before, when I was 16 and desperately trying to fight off the sin of homosexuality.

My church community fed me the narrative that I was struggling because I lacked masculine role models and did not have enough male friends. The latter was its own issue, but I tried to find every male Christian role model I could. This was mainly through music, since my little sister was engaged in a quiet rebellion of her own — bringing contemporary Christian music into our strict Jamaican Pentecostal household. In the first picture I remember of Jeremy Camp, he’s looking down into the camera. Both his eyes and the sky behind him are a soft blue. His hair is a mountain range of spikes. He looks rugged but gentle. I remember wanting to be in the picture with him. He’d be my brother and my guide into the type of young manhood where boys got dirty and then read their Bibles, which were smudged with sunscreen and carried the odor of grill smoke.

Jeremy became my rescuer. On days when I was defeated, when I had looked at gay porn and felt useless, I would walk the Bronx River Trail and listen to Jeremy’s hit song “Take You Back.” It’s still hard to think about the Sunday afternoon when I walked so far that I had to take the train home. I waited at the train station with Jeremy’s voice in my ears: “I’ll take you back always / even when your fight is over now.” He was with me when I got to college. I was often overwhelmed by “gay feelings” and would lie on my bed and let his lyrics wash over me: “Letting go of all my pain and all my fears.” I took up running — miles of his music. But my body was still on fire. No amount of post-run showers, no quantity of cold-water baptisms could cool me. I still found men sexually attractive. I wanted to be close to Jeremy because I found him sexually attractive, too — even though I buried this thought and told myself that I really did not like him, but instead wanted to be like him.

In 2014, I set out for Tennessee. The Bible Belt felt like my surest chance at Christian brotherhood, which was what I needed to be healed. I’d attend graduate classes at the Pentecostal Theological Seminary in Cleveland, Tenn., and work full time at the Lee University library. The first week, I called one of my new co-workers to see if she was aware of any youth group gatherings. She reached out to the many people she knew and offered me a quiet explanation: “Well, the youth groups meet on Wednesdays, but, you know … they are high school and college ministries.” At 22, I was too old. I later realized that my status as an employee at the university also meant I couldn’t participate in the kind of student life that would seat me next to a Jeremy at a bonfire. I continued to search for that gaze for the next three years, until it became, for me, a myth. In that sweet Southern nexus of Christian community, I was alone. But instead of turning again to Jeremy Camp’s baritone voice, I comforted myself by falling into the spaciousness of ambient music.

When I finally found the courage to yield to my therapist’s assignment, I excavated Jeremy from the place where I had buried good things. There was immense grief and possibility. I let myself write all of that softness down. I explored the question: What if I had found a Jeremy in Tennessee? That intuitive exercise brought me back to daily life in Cleveland, eating at the taco truck, getting my brakes done, thrifting, hiking near the Ocoee River — all with his warm presence. In seeing that individual — not the literal person Jeremy Camp, but the person I created in my mind from that gaze — I was able to look into the face of my desires. It was an experience that I named “Jeremy’s Valley.”

But I know of too many Black gay boys who have made a life in that ancient verbal construction, which captures longing on a cellular level: Oh, would that it were! They live in a subjunctive nightmare. The most difficult task for me has been integrating the lessons from that sweet valley experience with my public life. Finding that gaze again. Finding it in Nashville.

I later learned that the “Adam” picture of Jeremy is the cover art for his 2003 single “Right Here.” And when I finally revisited his album Carried Me: The Worship Project, I found another image from that same photo shoot. It is almost identical to the first, except here Jeremy is smiling — a woundingly handsome grin. Shockingly, the first emotion I felt was anger. I’d seen that same sharp-jawed smile all over Nashville. The men whose DMs I slid into who never replied. Then, at the bars, I’d see them in conversation with each other, those beautiful grins like a uniform. Sometimes, a white gay friend would introduce me to them with such exultations of their kindness. I was often afraid to reveal that I had already tried to make the connection. Too many times, after shaking my hand, they would never remember my name.

A very close friend once asked if Jeremy was like a messiah to me. I said no, angry at the question. I’d had late-night conversations with Black gay men about rejecting white supremacist beauty standards. I’d subjected my desires to examination by people whose opinions I held higher than my own vision. I lived under the hot lights of their disapproval for a long time. But then came the Valley. So the truth is — yes, he is. And we all need a Jesus. Or at the very least, someone to gaze at us, at long last, like we are a thing of wonder.

Plus we chat with hometown queen Aura Mayari and delve into the history of Play