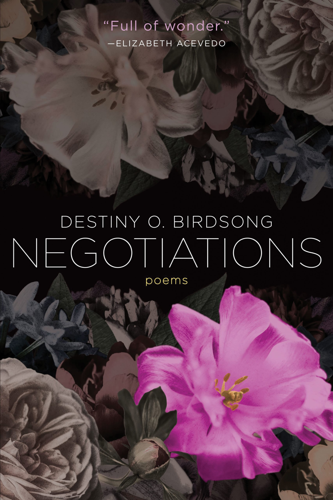

Destiny O. Birdsong wrote her first poem in seventh grade. It was inspired by an episode of Batman: The Animated Series, in which the superhero recites a line that Birdsong later learned came from a poem by William Blake. Though she admits that the poem “was terrible,” crossing pop culture with classic literature is a theme still present in her exceptional debut poetry collection Negotiations, which is available Oct. 13 from Tin House. The poems contain references and allusions to Langston Hughes and Bernie Mac, Toni Morrison and Cardi B, Ocean Vuong and Stevie Wonder. While Negotiations is peppered with scorching rebukes of American culture and politics, it is undeniably enchanted by American art and literature.

A native of Louisiana and proud Fiskite, Birdsong (who is a contributor to the Scene) earned her MFA and Ph.D. at Vanderbilt University — at the same time. It was in the MFA program that she first read Natasha Trethewey, A. Van Jordan and Tracy K. Smith, Black American poets who have influenced her alongside Shakespeare and Edna St. Vincent Millay.

I don’t believe that artists necessarily have a responsibility to speak to the moment — but Negotiations does, with startling results. Birdsong touches on 2017’s Women’s March, that same year’s white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., and the ill-fated gorilla Harambe, whom some Americans wrote in on the ballot for 2016’s presidential election. She’s also wary of the performative “#Resistance” that sprung up across social media since Trump’s election. She’s not coy about revealing the collected trauma inflicted on the American people by the current administration, but she places it in the context of white supremacy that’s rooted in the nation’s founding — and she knows there aren’t any easy answers. Birdsong opens the collection with the title poem, and these words:

My pussy is not made of microfiber.I can’t put it on my head to conduct business,

or plan insurrections. It’s not big enough

to hide in, dear reader. It’s not bulletproof.

It can be offered to neo-Nazis as a lure

for conversion therapy. That didn’t work

for Sally Hemings. I know it can’t work for me.

Other Birdsong poems are about sexual assault — they’re dark and complicated, and their titles begin the same way, with the words “My rapist,” as in “My rapist taught me the proper way to cook bacon.” The intimacy there is jarring — but so is partner rape, and she writes about the complex aftermath unapologetically and with courage.

The 34 poems in the volume are extremely readable, so much so that it’s tempting to rush through them. Don’t. Take your time. Ease into these poems. They’re worth it.

The Scene talked to Birdsong about Negotiations, writing through political turmoil, and who she’s loving when she writes.

The poems in the book reflect such a range of emotions and a range of tones. There’s unapologetic rage. There’s scorching rebuke. There’s lust, sorrow, memory and nostalgia, and there’s also comedy.

Yes.

I think that it has to do with many of the poems commenting on specific cultural moments that have happened in these past few terrible years, right? What was it like writing these poems during the Trump presidency, when the worst parts of our country’s character have been more visible than they’ve been in decades?

You know, for me, I think that there’s so many ways to be useful. I think that marches are useful. I think that legislation is useful. I think that acts of civil disobedience are useful. And I think writing is useful. … Of course, I feel like I’m perhaps more susceptible to that kind of inner sea change that happens when I hear something or when I read something, but I still think that we all have the capacity for that. I think that, if we didn’t, the Bible would not have been the first book printed. Even when we think about religious texts and how there’s this clamoring for reading and understanding them, right? That we all have this connection to the written word or just words from other people, even if you don’t necessarily have access to the word on the page. That communication is so vital and so valuable, and it’s how we understand each other, and it’s how we understand ourselves, and it’s how we understand our deities, whatever they may be. I do believe that, and so for me, that’s my role.

I’m never going to run for president, but I will write a poem. When I’m sitting down to write, I feel a certain sense of responsibility, like, “This is how I hope to make the world a better place.” That was a source of comfort while writing this book during that time. Because, really, I thought the book started in 2009, but it really started maybe around 2015. I think the oldest one in there is from late 2015. I was writing trying to understand my own trauma, like my own assault and what happened. And then the election comes, and I’ve been writing about living in a country run by an accused rapist. So I’m trying to understand that, and I’m trying to understand why white people are losing their minds and going to rallies with torches and chanting “blood and soil.” I’m like, “Is this the Middle Ages?” I’m trying to make sense of that, but also understanding that on the other side of the page is someone like me who is also trying to make sense of it. So, maybe my grappling with making meaning out of this time, maybe that narrative is also useful to someone else.

That is the reason I write Poetry with a big P. But I also just think on a micro level, it just makes me feel useful.

Do you have a reader in mind when you’re writing?

Yeah, oh gosh. … My friend Tafisha Edwards once repeated to me a question that a Black woman poet had posed to the workshop [she attended]. … “Who are you loving when you write?” I am unequivocally loving Black women of all types, all socioeconomic backgrounds, all iterations of womanhood, all of that. I’m loving Black women. But I also, many years ago, watched an episode of Oprah, and she was interviewing Vera Wang, the dressmaker. Vera Wang is talking about her journey and all of the stuff that comes into how she became a fashion designer. It cuts to Oprah, and Oprah is talking about how a Vera Wang dress feels. She says something to the effect of, “You know what, it feels like the dress was made especially for you.”

And, I was like, “That’s awesome — that’s how I want to write poems.” I want to write the kind of poem that when you step into it, it doesn’t matter what your particular metaphorical body type is, but the poem fits. So I really think of my ideal reader that way. I think, first and foremost, I’m always writing about the experience of being a Black woman, and my hope is that other Black women can relate to that experience. But if the dress fits, the dress fits. If it fits you, it fits you.

When the pandemic came to the U.S., as a journalist and as a devout James Baldwin follower, I was just like, “What is the role of art in this?” I’ve grown jaded in that respect. Our legislators need to step up and do this. Artists can’t save everything, you know?

Yeah, right, artists can’t pass a stimulus bill.

Exactly. But I think Negotiations definitely makes an argument that art can do a lot even if you feel like it can’t.

Yeah, exactly, I agree. It’s interesting because, last night, I had to turn in a letter that will go to some of my special first-readers, people who get free copies of the book. In that letter, I say that poetry isn’t magic. But I think what it does is make survival possible. There’s an Edna St. Vincent Millay sonnet, which is about love, how love isn’t everything. It’s not food. It’s not shelter. It can’t save a sinking ship. It can’t set a fractured bone. But every day, somewhere in the world, somebody is making friends with death just because they don’t have love.

For me, I feel that way about poetry and about literature. It can’t do any of those things, but when I have felt my most hopeless, I can turn to a book and it gives me something that pushes me to survive. Survival is the first step. If I can survive, yeah, then I can figure out how to do all those other things. I can figure out how to eat. I can figure out where to get food. I can figure out how to get shelter. I can figure out how to get health care. I can figure it out. But if I don’t have that hope that gets me out of bed in the morning, then none of that other stuff is possible.