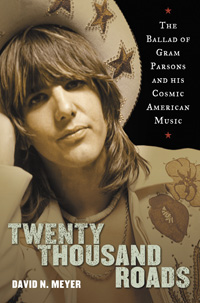

inger-songwriter Gram Parsons died in 1973 at age 26, but biographer David Meyer’s Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music still clocks in at over 500 pages. Picking up this doorstop of a book, it’s hard not to wonder whether the guy did a lot of living, or Meyer has done some very thorough research. In fact, it’s both. An early purveyor of mixing country, folk, blues and rock—what he called cosmic American music—Gram Parsons was born into wealth and privilege. The talented singer-songwriter is a“biographer’s dream and nightmare, a wealth of poetic contradictions and mythological motifs,”writes Meyer. Contained within Parsons’short life were everything from“suicidal parents, family wars over money, great talent undermined by inherited wealth and inherited addiction, innate genius at war with self-hatred and laziness, immense charm...rock-star sex, drugs and gossip...feuding wives and lovers, a mysterious death, and a bizarre aftermath.”

Meyer teaches cinema studies at the New School in New York City, and his writing has appeared in Entertainment Weekly, Wired and The New York Times. His books include The 100 Best Films to Rent You’ve Never Heard Of and A Girl and a Gun: The Complete Guide to Film Noir on Video. In Twenty Thousand Roads, this untiring researcher outdoes himself.

The book includes a prologue, epilogue, introduction, selected bibliography, discography, recommended listening (of which Meyer good-naturedly claims, “There is no attempt here to create a music nerd’s complete catalog, though the temptation is strong”), encyclopedia, source notes, album and song index and standard index too. Clearly he’s done the work required for a definitive biography, but he provides so much backstory, history and contextual information that it borders on obsessive. Chapters devoted to Parsons’family—such as his biological father’s childhood growing up in Columbia, Tenn.—are expected; whole sections detailing the origins of The Bolles School (the private academy Parsons attended for a total of three years), or where an underage Parsons bought beer, teeter on overkill. Still, Meyer’s writing is knowledgeable, engaging and very often funny.

It’s nearly 150 pages before Parsons graduates from high school. Once he does, the book picks up steam. He attends Harvard, drops out after a semester, moves to New York City, forms the International Submarine Band, heads for Los Angeles and joins The Byrds, fathers a child, teaches Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones“the mechanics of country music,”marries, forms The Flying Burrito Brothers, records two solo albums, and at 26, dies of a drug and alcohol overdose. It’s a short yet intense, tragic yet exasperating life.

“Contradictions are our essence,”writes Meyer, and he conveys Parsons’complexities with an astute eye for the telling detail and the insight that nails dead-on a certain time, place or person. Particular gems include his description of Branson, Mo. (“the family Las Vegas for retired Christians and their RV-driving grandchildren”) and the unexpected revelation that after his marriage to Gretchen Burrell, Parsons took his new bride on a honeymoon trip to Disneyland. Then there’s life on tour with The Byrds. Proving that rock musicians are capable of serious scholarship, one roadie from that time told Meyer, “We always took the Physician’s Desk Reference on the road, so we could read about our pills.”

Connections to Nashville are many. Parson’s musical partnership with Emmylou Harris—a particularly magical one—was only one of his many Music City associations. In 1968, The Byrds came to town to record their album Sweethearts of the Rodeo. They appeared on Ralph Emery’s radio show (with dreadful results) and drank moonshine in the parking lot behind Exit/In. They tried their best to fit in, writes Meyer: “In a sign of respect and sacrifice that may be difficult to properly appreciate forty years later, The Byrds cut off their hair. The band wanted to be accepted by Nashville.”

Ardent country fans weren’t so accommodating. The Byrds were the first rock band to perform on the Grand Ole Opry—still at the Ryman Auditorium then—and the audience booed them. Onstage with the group was pedal steel player Lloyd Green. “I was so embarrassed,” he tells Meyer, “I wanted to crawl off the stage…. I didn’t believe they’d get such rude, redneck treatment. I felt sadness that people would do that to musicians because of their hair.” (Today’s long-locked country performers must be grateful for The Byrds’ courage.)

To many, Parsons lived a glamorous life, but Meyer doesn’t glorify what he calls “the myth of the Byronic genius pursuing Rimbaudian excess in the service of his vision,”explaining that Parsons’“death offers not the slightest trace of romance.”Meyer sees past the legend to the crux of the story. Parsons was far from perfect, but artistically and creatively he took risks. He “possessed existential courage,” Meyer believes, and he left a musical legacy that bravely “described the self he could not bear.”