Kevin Hughes was a clean kid caught in a dirty business. In 1989, he was the Nashville chart researcher at Cash Box magazine, which had once ranked with Billboard as the industry’s most prestigious trade paper. For a 23-year-old who loved music and had made up his own charts growing up in rural Illinois, it should have been a dream job. The magazine delivered every aspect of the music industry, spotlighting both new and established artists and records. Its record charts ranked the nation’s most popular albums and singles. But Hughes had walked into a dark netherworld of tough-guy record promoters who wore gold chains, drove Cadillacs and bilked aspiring singers out of fortunes. He soon learned these were people whose livelihoods depended on doctoring the very charts over which he had been put in charge.

By the first week of March, Hughes was telling people that he had a big decision to make. He told his parents he wanted to come back home the following weekend to sort some things out. He never made it. On Thursday, March 9, 1989, he was gunned down on Music Row, the dream dying in a pool of blood on a cold, dark street.

The Nashville dailies reported at first that it was a robbery gone bad in an area where violence was on the rise, but those who knew the situation suspected at once that it had been a hit. The names of two Music Row record promoters dominated the speculation that swirled instantly and never fully died, even after more than a decade without an arrest. The first, Chuck Dixon, died last December in Nashville, although plenty of people who knew him would feel more comfortable if they could see the body. The second, Richard F. “Tony” D’Antonio, was arrested in Las Vegas two weeks ago and charged with first-degree murder.

The street hypothesis is that Dixon—a self-styled godfather of country music—ordered the murder, and D’Antonio carried it out. The police have released little information, but D’Antonio’s arrest signifies that they subscribe to at least the latter half of the theory.

Both men knew Hughes well. In addition to working as a record promoter, D’Antonio had been Cash Box’s director of Nashville operations; he had, in fact, recruited Hughes as an unpaid intern from Belmont University. Dixon was omnipresent at Cash Box for many years. His clients dominated the paper’s independent country chart, and he was close to its Los Angeles-based owner, George Albert. When Hughes was unwilling to participate in a well-known system of chart manipulation that helped defraud an endless string of naive country singers, the theory goes, he was killed.

In his heyday, Chuck Dixon was flashy, well dressed and obsessed with the Mafia. “He watched The Godfather—parts 1, 2 and 3—four or five times a week,” says Gary Bradshaw, an enemy-turned-partner of Dixon’s. “It was unreal.”

Dixon, Bradshaw says, had once lived in the projects, poor and drinking too much. The memory of those days would stay with him. “He was scared to death of being broke again. Money meant everything in the world to him. Nothing else meant anything.”

A friend introduced Dixon to an established Nashville record promoter, who gave him some lists of radio stations, answered his questions and threw in a few pointers. It wasn’t long before he was established, telling others to back off from places like Cash Box that he increasingly thought of as his territory. At some point, say those who knew him, he decided that intimidation would be a helpful business tool. He would approach acquaintances in his Cadillac, roll down the window and say, in a graveled, Godfather voice, “Hey, I want to see you.”

“He used to like to play that mob role to the hilt,” says Tim Malchak, a singer who used Dixon’s services in the late ’80s and has generally good memories of him. “He liked to flaunt the fact that he had a lot of cash.”

“If you didn’t wear a lot of jewelry around there, then you weren’t a promoter,” Bradshaw remembers. “It was part of the show. I had a gold necklace, Nino Cerrutti suits. I came to Nashville one time in Levi’s and a shirt. Chuck took me out to a clothing store and bought me a new suit, and he said I had to have these Florsheim shoes.”

Dixon’s circle included D’Antonio, who referred to himself as “The Tone” and fancied himself a Mafia type as well. Dixon, though, was the undisputed boss.

“He orchestrated everything with Bradshaw and Tony,” says Robert Gentry, then an independent promoter who teamed up for a time with D’Antonio. “I mean, they used to kiss his ring, you know what I’m saying?”

D’Antonio worked briefly as an assistant to a promoter, but a chance encounter with a former Cash Box editor gave him an unexpected career boost.

Tom McEntee had been a New York Cash Box staffer in the 1960s, when the magazine was at its peak of power and prestige. He had moved to Nashville and opened an industry tip sheet called The Country Music Survey—founding as an adjunct the annual conference that became the Country Radio Seminar. He then promoted for both major and independent labels. As the mid-’80s approached, though, he was between gigs, playing the Pac-Man machine in the lobby of the United Artists Tower on Music Row to kill time. D’Antonio started hanging around the machine as well, and the two became friendly.

Cash Box Nashville vice-president/general manager Jim Sharp had just left the magazine, and owner George Albert hired McEntee to replace him. One of his first acts was to hire D’Antonio.

“It was my first day, and I needed bodies,” McEntee says. “Tony had worked in Vegas. I think he told me he had worked the crap tables and knew numbers. If somebody puts down a $6 bet and it’s 35-to-1, you’ve got to be instantly figuring the payoff, and there are a lot of bets going around, so you had to be good with numbers. I said, 'Come on, I’ll teach you how to be the chart man.’ He worked his ass off seven days a week.”

Six months later, D’Antonio was handling the charts more or less himself. The paper had added more reporting stations and “he was overwhelmed,” McEntee says. “He needed help, and I didn’t have the budget to hire. I told him to call the colleges—MTSU, Belmont—and ask for interns. He interviewed this kid and said, 'I like him. Can we put him on?’ I interviewed him too and thought he was fine, so I said, 'Go ahead.’ ”

The unpaid intern, who would later drop out of Belmont when the job became full-time, was Kevin Hughes.

Kevin Hughes grew up outside Carmi in southeastern Illinois. By the time he was a freshman in high school, he was obsessed with music, studying the Billboard magazines his parents would bring home from Evansville, and making up his own charts. He entered Belmont University in 1983 to study the music business, later changing his major to marketing. A fan of positive music, he was drawn more to rock and contemporary Christian than to country—he was an Amy Grant fan, and he listened to everything from Barry Manilow to Metallica.

He was an intern at the Gospel Music Association before taking the Cash Box job, thrilled for a time to be part of a business whose calling card is fame, glamour and respectability.

Eventually, though, he realized that much of the business was a churning engine of ego and greed, fed by a constant influx of fame-hungry singers with various levels of talent and accomplishment. They are fair game for all manner of businesses—recording studios, record labels, managers, record promoters—on a sliding scale of legitimacy and respectability, many with enough links to well-known companies and artists to provide an irresistible sheen to the newcomer.

“There were hundreds of them,” Bradshaw says. “There was a turkey farmer down in Mississippi who got ripped off for half a million dollars by someone I knew. Another lady from Ohio told me she spent $450,000 on one album project for her husband, and I have to believe her. I personally was never fortunate enough to get involved in one of those deals. I do know a lot of these people who came here spent 25-, 30-, 40-, 50-, 60-thousand dollars like clockwork.”

Bradshaw, in fact, says he got into the business himself after being taken for $17,000 trying to help his son’s singing career. Singers would quickly spend thousands—or tens of thousands—of dollars just getting a song recorded. Then it was time to talk with record promoters, who charged $1,500 or more to work a single. The promoter’s job was to convince radio stations that reported to Cash Box to add the single to the station’s playlist. With enough adds, the record would start moving up the Cash Box Indie Singles chart and might even crack the main Country Singles chart. The service seldom came as advertised.

“I’d have certain disk jockeys who would add the records, and Chuck [Dixon] would have some,” Bradshaw says. “The trick is that most of the time the record wasn’t getting played or even delivered. I spent a lot of time going around to radio stations, and I never did hear one of our artists getting airplay.”

“I called up the radio stations,” says former promoter Robert Gentry, “and some of them told me, 'I’m going to take care of you because you take care of me, but as far as actually playing, I ain’t gonna play that crap—I’ll lose my job.’ And they’d send us fake charts.”

That, though, was not in itself enough to make the system work. “The fix was in at the office, not the radio stations,” Gentry explains. “Tony was screwing with the charts. It would be too difficult to get 40, 50 or 60 stations sending phony playlists. I had plenty of stations where I had four or five places where I could pick whatever I wanted, but to get it to No. 1 on anything you’re going to have to move it up the chart at a lot of stations, and that can’t be. That part was fixed at the office, and there was a direct relationship between advertising dollars spent at the magazine and position on the chart.”

The bottom-line payoff was supposed to be a buzz and a chart presence irresistible to the major labels. “The pretense of the promoters,” Bradshaw says, “is that if you do well on the independent charts, the majors will suck you right up, which was in fact just the opposite. Most majors wouldn’t touch somebody on those charts.”

Working the independents, Gentry says unequivocally, amounted to “just screwing them out of money.”

The scam involved keeping a stable of disc jockeys at some reporting stations. “Chuck told me at one time he was paying out $2,000 a week—for everything from car tires and tune-ups to house payments—to disc jockeys,” Bradshaw says. “You’re talking about guys who were making $200 a week and didn’t have the money to live like the stars. They’d come up for [the Country Radio Seminar] and get to hang around George Jones or Garth Brooks, and it was a big thrill for them. They were like groupies in a way.”

The idea, Gentry says, was to shower the jockeys with gifts—free trips to Nashville, free hotel rooms, registration to the Country Radio Seminar, even whores and drugs. “That’s what we did,” he says. “You had to keep them in your pocket. And then when they didn’t play ball, you came back and said, 'In the last year from me alone, you accepted over $8,000 in gifts and cash. I wonder what your boss or the FCC would say about this.’ ’Cause now you own ’em. You get ’em in deep enough, and then you own ’em.”

At the Cash Box office, the promoters maintain that executives and editors had varying degrees of knowledge. “A lot of them were good guys, but people needed jobs, man,” Gentry says. “Nobody could get jobs with the majors, and everybody’s trying to make a buck in Nashville. A lot of people did a lot of things that were less than credible then to pay the rent.”

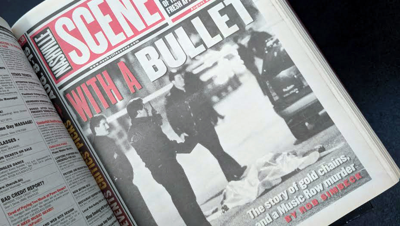

Cash Box was once a titan. In 1958, a few months after Billboard began placing a star next to titles showing “outstanding upward changes of position,” Cash Box introduced its own version, called the “bullet.” The phrase “with a bullet” would become industry shorthand for a hot record’s climb. While an editor in New York in the 1960s, McEntee introduced the bullet to the country chart.

By the 1980s, though, after a particularly nasty industry slump, the publication had hit much harder times. In Nashville, independents moved in to fill some of the gap left as the majors paid less attention to the magazine.

By the end of his first stint at Cash Box, in the 1980s, Jim Sharp says, “I saw the independents surge into the charts, and I kind of got a firsthand view of it from many of those promoters. I didn’t see anything real wrong with it, but when I was gone, people would come to me and say, 'Look what’s going on here,’ and bring it to my attention.”

The next stint belonged to McEntee. Albert had delayed hiring him until several months after Sharp’s departure, and without a leader, the office descended into what McEntee characterizes now as “chaos.”

“I had no clue how bad a shape it was in, or I don’t think I would have accepted the job,” he says. “I had one person left on the staff, and he had already turned in his notice. I had to grab people, and there was no budget. [George Albert] was the tightest guy with a buck I’d ever seen.”

It was at that point that he hired D’Antonio. Asked if there might have been chart manipulation at that point, he says, “There might have been, but I don’t think so. You get a sense. I did the charts myself, and that’s why I taught him. I would be well aware of what records were coming in. We started the independent chart just to have a place for independents. He might have manipulated the bottom 20 of those, but that’s so incidental. I don’t believe that was happening with Tony.”

He says the pressure of reinvigorating the office led to a recurrence of childhood asthma. Between the pressure and his health, he admits he made errors in judgment.

“Before I left, I started noticing things, but being overwhelmed with work, I wasn’t sizing people up as well as I could have.... I started to notice Chuck [Dixon]. He was pretty flashy. He had a little bit of an attitude. But the chart information was right where I could see it. At the time, it didn’t appear to me there was any doctoring going on, but Chuck referred to stations he called as his 'pocket stations,’ those he felt he had in his pocket. Whether that was through payoffs or what, he never said.”

McEntee says his health finally forced him out. “The pressure was incredible. It put me in the hospital twice. I said, 'I don’t need this.’ ”

At that point in 1987, owner George Albert made Tony D’Antonio the office manager. “He had a little over a year and a half with Cash Box and a couple of months in promotion,” McEntee says, “and now he’s running a magazine. I figure you should know the business before you’re running a magazine, but that’s not the way George Albert saw it. He thought they were figureheads.”

But Tony D’Antonio was no figurehead. He brought cronies on board, and the fraudulent system became fully established. Sharp, who had occasionally consulted for McEntee, declined D’Antonio’s requests for advice. “I have to say I never did go in the office when he was there,” Sharp says. “Once Tony took over, I didn’t even communicate with him. I didn’t feel good about it.”

D’Antonio eventually left—reportedly forced out over sexual harassment of a female employee—and after problems with similar regimes, during which time Hughes was killed, Albert asked Sharp to come back again. But D’Antonio went back into promotion, working closely with Chuck Dixon.

“When I went back to try to clean up the thing, they had put three or four crooks in different jobs,” Sharp says, “including a thug kind of guy who would go threaten people.... I got a real close view of that, how they were doing it. They wanted to play the role of gangsters—the rings, the sunglasses, the gold chains.... We had to get the authorities involved. Tony had already moved out, but Dixon and Bradshaw were working together. While I was there, they worked within the rules of what I set up. We had a few run-ins. They were trying to manipulate some stations. I saw the owner/publisher was not in complete compliance with what needed to be done, but all you can do is voice your objection.” Acquaintances theorize that behind the chaos was a scenario in which Chuck Dixon had presented George Albert with a scheme to greatly increase both their revenue streams.

“I wouldn’t doubt that,” Sharp says. “I often heard Chuck Dixon talking to Mr. Albert about that. My last conversation with Albert and Dixon was to the extent that there was another promoter trying to promote some records, and they were trying to lock him out.”

Sharp also had a run-in with Dixon, who was trying to add more of his “pocket” stations as reporting stations. Sharp had agreed to come back for two years, and he decided to see it through, “to get my money and not cause any problems. I saw that it wasn’t going to change, or I would have stayed around. The owner and publisher wanted the credibility on the one hand, because the major labels weren’t even talking to him anymore about advertising, but at the same time he wanted all the money from the independents.”

Kevin Hughes’ younger brother Kyle visited once for two weeks and recalls Kevin taking him to Chuck Dixon’s office. “At that time, he didn’t say a bad word about him,” Kyle Hughes remembers. “But then I went home, and later he started saying real negative things about him and the promoters and different things. He said he’d been offered some things.”

Robert Gentry, the former promoter, is convinced Hughes was being forced to go along with the chart doctoring at the magazine. “All of a sudden, my records weren’t charting,” Gentry says. “Nothing. This was right after I had split with Tony. So I started getting the radio stations to fax me their playlists, because I knew something was up, and I wanted to prove it. I’d go up there on the day when they did the chart and I’d say, 'I’ve got 27 playlists from radio stations with adds on them for this song.’ Kevin goes, 'Well, you know, sometimes they send y’all a different playlist than they send us, I guess. I don’t know.’ But, see, he was being forced to do this, to make up this phony chart.”

Gentry says he was threatened and that D’Antonio “more or less told me, 'Nothing’s gonna get on the chart unless you get us added on to promotion.’ ”

During the week of the 1989 Country Radio Seminar—which annually brings the entire industry to Nashville—Bradshaw met Kevin Hughes for the first time. Bradshaw, who was still based in Texas, had been talking with him by phone for months. The two met in an elevator at the Opryland Hotel, where the event was held, and Hughes was with his friend, singer Sammy Sadler.

Sadler, also a Texan, was enjoying the kind of success the Cash Box system was designed to foster. His “Tell It Like It Is,” a remake of the 1967 Aaron Neville pop hit, had debuted Dec. 31, 1988, at No. 8 on the Country Indie Singles chart and at No. 76 with a bullet on the Country Singles Chart. Three weeks later, it had jumped from No. 7 to No. 2 with a bullet on the Indies chart, and was at No. 58 with a bullet on the main chart. It stayed at No. 2 for two more weeks, and rose to No. 47 on the main chart before beginning to fall off both. It had been a good run.

Sadler had been featured in the magazine’s “Indie Spotlight.” He had done all the right things. And the promoter who had made it happen was Chuck Dixon.

Many people remember seeing and talking with Hughes that week. Keith Albert, grandson of the Cash Box owner and then chart manager, met Kevin at the Country Radio Seminar.

Gene Kennedy, owner/president of Door Knob Records, had lunch with Hughes the week before his death. “He just didn’t seem to be himself,” Kennedy says. “He said, 'I’ve got a lot of pressure right now. It’s at the office, something I’ve got to make a decision on.’ I saw him Saturday at a seminar, and he appeared to be in that same kind of mood.”

Gentry ran into him in the parking lot of the Opryland Hotel and asked him to come back inside for a drink. “He was all freaked out, looking over his shoulder. He said, 'Man, I’ve gotta go. I want to talk to you later about something, but right now, I need to go.’ I’d never seen him nervous like that. I knew something was up. I truly believe he was getting ready to blow the whistle on the whole thing, because this is the kind of person he was.”

Hughes called his parents early the following week. “He was going to come home that weekend, and he told us that he had something that he wanted to talk to us about,” says his father, Larry Hughes. “We kind of suspected what it was. He didn’t like some of the stuff that was going on there.”

On Thursday, March 9, Kevin was working late, as he often did. The chart would be released the next day, and he would often field calls from promoters wanting to know where their artists’ records stood. Kevin compiled the charts by hand, without computers, and he worked meticulously, often until late at night.

Shortly before 9:30 p.m., still at the Cash Box office, Kevin spoke with his brother Kyle, who was at home studying for a physics test. “He told me he wanted to tell me some things, but he didn’t want to tell me over the phone,” Kyle says. “I actually heard a knock on the door. He kept talking to me, and then I heard another knock. I think I remember him saying, 'Sammy’s at the door. I’ve got to go.’ Then he told me he loved me. We hardly ever expressed our feelings, and he never told me that over the phone.”

Kevin Hughes’ friend, singer Sammy Sadler, told the Banner that he and Hughes stopped at the Captain D’s on West End Avenue, then dropped by the offices of Evergreen Records, Sadler’s label, at 1021 16th Ave. S.

Sadler said he called his mother in Leonard, Texas, and that Hughes then spoke briefly with Sadler’s father. They then planned to return to the Cash Box office to get Sadler’s truck.

They left Evergreen at about 10:20 p.m. and walked to Hughes’ blue ’88 Pontiac Sunbird, parked across the one-way street. As they were getting in, a man wearing a ski mask, gloves and dark clothing—D’Antonio, according to police—stepped out of the shadows and shot, hitting Sadler in the shoulder. Hughes ran down the street. If police are right, it was D’Antonio who then ran after Hughes, firing several times and hitting him once. Hughes fell to the pavement. D’Antonio walked to where he lay and put two bullets in his head.

There was a memorial service eight days later at the Belmont Church on 16th Avenue. Tony D’Antonio “never came for the memorial service,” Door Knob Records owner Gene Kennedy remembers, “and they’d worked together.” But, he says, Chuck Dixon came “and sat in the very last row—by himself. I’ll never forget that.”

After D’Antonio’s recent arrest, the Metro Police Department officials said investigative work and new interviews of witnesses “led to a stronger than ever interest in D’Antonio as the suspected gunman.”

Many of those interviewed suggested that Dixon’s death may have prompted a renewed investigation. “I knew it was coming once Dixon died,” Sharp says. “I knew somebody was going to start talking because they weren’t going to be afraid anymore.”

Nine months after the slaying, homicide Lt. Tommy Jacobs said that since Hughes and Sadler’s stop at Evergreen was unscheduled, he thought the slaying grew out of a chance encounter. Now that authorities believe the murder was related to Hughes’ work at Cash Box, they have not said whether they still think the stop was unscheduled or how they think D’Antonio would have been near Evergreen Records, prepared to kill someone who was not expected to stop in.

Kevin Hughes’ father was a farmer who had attended Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Dallas and was an unpaid staffer at an Illinois-area Baptist Association at the time of Kevin’s death. He is currently a teacher. “We were grateful for the arrest,” he says. “We saw it as an answer to prayer. And now we’re just praying for conviction.”

“I just hope this all does come to light, and the wrongdoers are brought to justice,” his son Kyle Hughes adds. “I hope they get everybody involved. I hope it all comes out. He was a great brother. I remember how much he would protect me and teach me things he didn’t even know he was teaching me. He would give up anything to help somebody out.”

Thirteen years after Kevin’s death, his mother weeps when she hears those who knew her son remembering him so fondly. The former record promoter, Robert Gentry, for example, says of Kevin Hughes: “He was the only person I knew in the music business who I could look in the eye and say, 'That guy’s gonna make it to heaven.’ ”

Hearing that, Kevin’s mom says, “Yes, we know where he is.”

To report additional information about the murder of Kevin Hughes or the independent label and promotion scene in the late 1980s, contact editor@nashvillescene.com.