The Route: Fifth Avenue North to Broadway. Broadway to West End. West End to Centennial Park.

Abandoned Scooters: 30

Cranes: 28

Once a month, reporter and resident historian J.R. Lind will pick an area in the city to examine while accompanied by a photographer. With his column Walk a Mile, he’ll walk a one-mile stretch of that area, exploring the neighborhood’s history and character, its developments, its current homes and businesses, and what makes it a unique part of Nashville. If you have a suggestion for a future Walk a Mile, email editor@nashvillescene.com.

The Nashvillians who led the famous women’s suffrage march in 1914 were a sharp bunch. For one thing, they scheduled their parade for May 2. Contemporary newspapers noted the pleasant weather, perfect for a shuffle from the Tennessee State Capitol to Centennial Park.

Following in their footsteps isn’t so easy in 2020, particularly in late July. Middle Tennessee’s infamous summer humidity doesn’t relent, nor does Nashville’s sidewalk-encroaching construction or the apparently nearly constant updates to the city’s premier urban park.

Rather than following the exact route laid out by Anne Dallas Dudley, Juno Frankie Pierce, Carrie Chapman Catt, Catherine Talty Kenny and others (more on their efforts in this week’s cover package, which starts on p. 10), this month’s walk — twice as long as normal — began instead at the Houck Building at 240 Fifth Ave. N., which served as headquarters for the Nashville Equal Suffrage League and was the rally point for its members the morning of the parade. Built in 1889 by the Jesse French Piano Co., the ornate building is well-maintained on the upper floors, a reddish-beige paint scheme giving it the look of terra cotta when the early-morning sun strikes it.

At the time of the 1914 march, Fifth Avenue was Nashville’s chief retail district. But the Nashville Equal Suffrage League showed a spark of prescience — 46 years later, the Woolworth’s lunch counter was the site of the first sit-ins of the city’s civil rights movement, marking Fifth instead as an epicenter of activism.

Long before either event, though, Fifth Avenue was the site of accomplishment for a remarkable Black woman. In 1840, Sarah Estell, a free Black woman, ran one of the city’s most popular ice cream parlors and sweet shops. For two decades, her “ice cream saloon” near St. Cloud Corner was a favorite stop for businessmen as well as parishioners at nearby McKendree Methodist. St. Cloud Corner sits on one corner of one of the city’s most architecturally interesting intersections. Across Fifth is the Fifth Third Center, and across Church from there is Downtown Presbyterian Church, which neighbors the Cohen Building. All four are, to some degree, Egyptian Revival. The church, built as a copy of the Karnak Temple, is the truest example — in fact, one of the most notable examples of the style anywhere — but all the aforementioned buildings show hints of the style, which was in fashion for a relatively short period of time in the mid-19th century. Built in 1986, some 130 years after the peak of Egyptian Revivalism, the Fifth Third Center (which once housed a YMCA on its uppermost floors) is a sort of post-modern take on the form.

It’s evermore difficult to see the Ryman Auditorium while descending Fifth these days, what with the influx of shimmery towers all around (and the construction that forces view-interrupting street crossings). But it stubbornly remains where it has served as Nashville’s most venerated venue since 1892. Well, venerated except for during the 20 years it was abandoned. And it wasn’t venerated by Roy Acuff, who wanted it torn down when Opryland opened. And it was almost the victim of a massive car bomb in 1979 (a nearby strip club was the actual target). But still it stands, empty at the moment, like most other venues, but no doubt coming back.

Blessedly, Lower Broadway is largely empty at this early hour too, but for a handful of stroller-pushers and perambulating downtown workers. If bright sunshine and wide-open spaces are really the key to fending off COVID-19, 7:45 a.m. is a good time to walk through the Neon Canyon. Twelve hours or so later ... not so much.

The Suffs made their turn onto Broad at Sixth Avenue, having marched down Capitol Boulevard (now named for Dudley). It is not a path followable today, with the former convention center blocking the way. Construction continues there on, among other things, the forthcoming National Museum of African American Music.

Over the scramble crossing at Fifth and Broad — far less nerve-racking in the morning than when Broad is abuzz — sits Bridgestone Arena. Hockey isn’t back at the Tire Barn, but the Smash Car — festooned in the colors of the Predators’ playoff opponent, the Arizona Coyotes — is ready for the sledgehammer nonetheless.

The suffrage marchers encountered much support on Broadway 106 years ago. Mayor Hilary Howse declared a half-holiday for the city, whatever that means, and the “working girls” (a term that appeared in The Tennessean’s recap, and not as a euphemism) who couldn’t get the day off rained yellow roses from the windows of the office buildings and stores that lined the street.

Today, the street is lined with orange cones, and yellow roses are nowhere to be seen — though yellow tape blocks sidewalks in front of a building advertising “rentable living,” because apparently Nashville is incapable of using the word “apartments.”

At the top of the rise of Broadway, construction cools, and a streetscape of architectural mishmash begins. There’s the staid Classicism of the Masonic Hall, which hides an opulent interior (or anyway, so say those who’ve been within). Hume-Fogg is a limestone castle. First Baptist Church and Christ Church Episcopal are in various versions of Gothicism, as is the old Customs House (opened by President Rutherford B. Hayes; during his visit to Nashville, he’s said to have enjoyed the vices of Printers Alley, drawing the ire of his famously teetotaling wife “Lemonade Lucy,” who allegedly berated the president from the stage of one of the alley’s venues). And then there is the boorish Brutalism of the Estes Kefauver Federal Building, a building so bland and charmless there’s little doubt why it’s named for a man famous for trying to ban magazines featuring pin-up models.

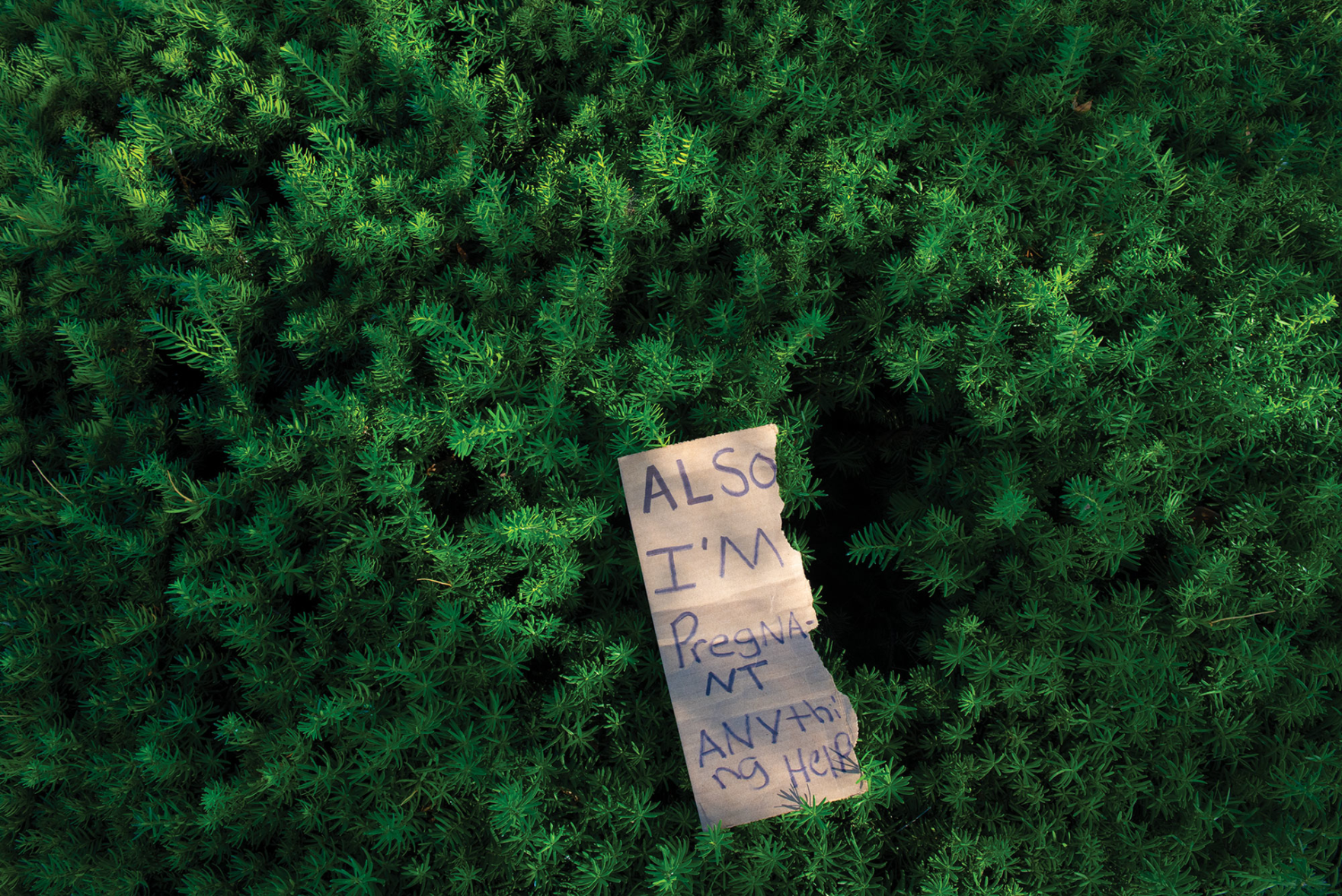

An entrepreneur, perhaps looking for a side hustle during Covidtide, has no such qualms about the commerce of titillation, having posted a flier with a phone number urging passers-by to “hit me up” for, well, sexting, apparently.

Across from the Frist Art Museum is more construction, which can now continue without remorse. When the project began, the British Museum pulled its loaned collection of priceless Roman artifacts, worried that the blasting would destroy the treasures.

Broadway flies over the actual railroad gulch nearby (officially the Kayne Avenue Yard), though this morning, few trains are there, the coal haulers having long since made their way through town. Another gulch is visible at George Davis and Broadway: that which was blasted out to lay down Interstates 40 and 65, creating a physical break between downtown and points west. The layers of limestone make it obvious why construction in these parts is so teeth-rattling.

Prices are down on the used cars at the lots between the interstate and the “split,” where The Nashville Sign desperately continues its bid to be A Thing.

The Suffs took the right fork to go down West End. Then as now, there was no Lake Palmer. In 1914, it was because no one had yet blasted down scores of feet for a project that wouldn’t be finished. In 2020, it’s because, finally, blessedly (except for those who enjoy casual water in the middle of their city), buildings are going up where, for years, Nashville’s most famous abandoned building project turned into a lake.

Signs of an overheated real estate market and an economic downturn: Multiple “For Lease” storefronts and a billboard where even Sperry’s, which has never wanted for well-heeled customers, is advertising. First Bank posts a sign telling its customers the lobby is closed “until futher notice.” Surely the sign’s been up for months, so let’s say “futher” isn’t a typo (because certainly it would have been corrected), but rather a nod to the disappearing Old Nashville accent — that of newsman Larry Brinton and Ed Stratton, the voice who called Emma’s “the SU-poo-lative florist.”

The Suffs would have passed the Cathedral of the Incarnation, though it wouldn’t be officially opened for services until July 1914. Catherine Kenny may have nodded and smirked as she passed; a devout Catholic, Kenny nonetheless bucked the views of her church and many of its members by being a tireless advocate for suffrage.

The women would have walked by the Tennessee Governor’s Mansion, then on West End near the Loews Vanderbilt Hotel and the Caterpillar Building. Gov. Ben Hooper was — rather unusually for the time — a Republican, and was the home’s occupant in 1914. Hooper was a progressive, pushing for compulsory education and requiring women be paid directly by their employers (many companies at the time paid the women’s salaries to their husbands). There’s not much in the record for his feelings on suffrage, though his last surviving child, Janella Hooper Carpenter, told The Newport Plain Talk her sister would give pro-suffrage speeches in the mansion at the age of 9. Carpenter was 105 when she died in 2014.

West End rolls past Vanderbilt University here. It seems the university hasn’t been tending to its famous trees — magnolias and ginkgos, most notably — In These Times, but the unkempt branches provide much-needed shade along the sidewalks in steamy summer weather.

Just as West End nears its flatiron intersection with Elliston, it passes the Homewood Suites, which is notable only for the piece of public art at the center of its roundabout entrance: a large guitar, topped by smaller guitars, topped by what appear to be Sputnik chandeliers festooned with music notes, all of it spinning around. It’s a head-scratcher, but at least there aren’t any nude folks on it.

The women wrapped their march with a series of speeches — praised by both The Tennessean and the Nashville Banner — in Centennial Park. Today there’s a historical marker near the Centennial Arts Center, and an Alan LaQuire statue featuring depictions of Anne Dallas Dudley, Abby Crawford Milton, Frankie Pierce, Sue Shelton White and Carrie Chapman Catt is near the Parthenon.

The ongoing revitalization at Centennial Park makes accessing the latter a bit of a chore, what with having to determine which roads and trails are open and unblocked by chain link. But like a fight for equality, it’s well worth the longer walk.