Once a month, reporter and resident historian J.R. Lind will pick an area in the city to examine while accompanied by a photographer. With his column Walk a Mile, he’ll walk a one-mile stretch of that area, exploring the neighborhood’s history and character, its developments, its current homes and businesses, and what makes it a unique part of Nashville. If you have a suggestion for a future Walk a Mile, email editor@nashvillescene.com.

The Route: From Cleveland Park, right on Cleveland Street, then right on Meridian Street. Right on Vaughn, left on Lischey Avenue and then right on Vernon Winfrey Avenue, continuing to North Sixth Street and back to Cleveland Park.

Cranes: 2

Abandoned Scooters: 0

Birds squawk at the morning runners and dog walkers around Cleveland Park. This July day started off still but pleasant, the usual breakfast-hour stickiness staying away, at least for now. The avian set is taking advantage of a baseball diamond flooded by overnight showers, using the drowned basepaths as a birdbath and observing goings-on from the islet formed by the pitcher’s mound, up above the shallow water like a miniature seamount peeking over the swell of a tiny ocean.

Cleveland Park is largely open space with its fields dotted by trees. A more substantial treeline runs along its eastern edge as a largely ineffective sound barrier from the rail line.

The public pool is empty at this hour, its cool waters only slightly disturbed by the occasional breeze rippling its surface. The community center stands nearby, home of the local Boys & Girls Club. The benches on the basketball court show evidence of what the kids are working on. Dozens of Ziploc bags are taped up, each with a couple of inches of dyed-blue water. In black marker, the future scientists have written various best-effort spellings of “evaporation,” “condensation” and “precipitation,” indicating these little bags are meant to demonstrate the water cycle. They’re doing a good job too — the water in most is well below the lines showing how deeply they were filled originally, steam is built up around the zipper, and droplets are flowing down the plastic.

Between the hoops courts and the (netless) tennis courts: three hard-surfaced alleys, each with gutters running down the long ends. The alleys are too narrow for pétanque and the surface too hard for bocce. There’s no crown as in lawn bowls and no markings for shuffleboard. The gutters make no sense for horseshoes, and there’s no place for a post to go in the ground in any event.

Across North Sixth Street, workers are building three new houses in a row south toward Cleveland Street. They’re still just frames and lumber, and so it’s hard to say if they’ll fit the cottage and wood-sided character of the road in style, but it’s obvious the new builds will be much larger than their neighbors.

West on Cleveland, a new condo complex is getting its finishing touches. It already has the requisite mural — it’s apparently meant to depict Jimi Hendrix, though the guitar is all that’s really obvious to the non-abstract eye. Cleveland is busy with workers as the sun climbs higher. A utility worker wraps up his duties and reopens the sidewalk across from Murrell School (officially it’s two schools: Murrell at Glenn School and Glenn Enhanced Option Elementary; the original Murrell School was in Edgehill) with a smile, the sweat dripping into his graying beard.

The houses along Cleveland are mostly wood-sided (or at least reasonable facsimiles of the same) but clearly are in a range of vintages. The lots are mostly elevated, and the homeowners take pride in the little swaths of green along the sidewalk. One well-landscaped patch around the mailbox urges passers-by to please scoop if their canine pal poops. Another fencerow is filled with more echinacea than a supplement store.

Untended plants have, however, taken over much of the lot at the northeast corner of the Cleveland-Meridian intersection. An abandoned church — originally built in the 1920s as Meridian Street Methodist, but later serving as home to Ray of Hope Community Church — sits for sale, along with its massive four-story annex behind, its New York City owners having let the bushes burst into scraggles and allowed moss to slicken the stairs. The sunlight catches the wide stained-glass windows, dull now after years without cleaning.

Across Meridian, more history is boarded up: Fountain Blue (or Blue Fountain), the stately home built by some member of the McGavock family. The property was a gift to James McGavock, a son of David McGavock, an early Middle Tennessee settler. But James was murdered on Whites Creek Pike in 1841, and Nashville records from before his death don’t indicate a large house on the tract. His daughter Lucinda inherited the Fountain Blue property. She was married to Jeremiah George Harris, who — in addition to palling around with James K. Polk and holding various sinecure jobs — founded the Nashville Daily Union newspaper. He wrote to Polk in 1844, after a trip to Europe, that his home was under construction.

In any case, the property bounced around various McGavock descendants for a while and later became home to, among other people, Alonzo Webb, who worked for the Nashville school system as supervisor of writing and drawing. He purchased the house in 1905, but spent most of his time at another home on Wilburn Street. He sold part of the land — though not the house — to his boss, school superintendent J.J. Keyes. The home was converted to apartments around 1915 and was owned by the Ray of Hope Community Church for a time. In May of this year, a local investor filed paperwork asking for the property to be rezoned for a brewery.

As the sun creeps higher, over the ridges girding Nashville and the trees along Meridian and Vaughn, summer stickiness arrives, the brief respite from a typical July now a memory.

Many houses on Vaughn, particularly along its southside, follow the same familiar pattern with L-shaped porches and two front doors, perhaps all built from the same Sears & Roebuck kit a century ago. The houses turn more modest (and more modern) on Lischey, home of Hermann Holtkamp Greenhouses, which claims to be the leading grower of African violets in the world. Near the Holtkamp operation is a historical marker noting the original location of Joy Floral, which grew (forgive me) to become the South’s largest florist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Winfrey Barber and Beauty Shop is at the corner of Lischey and Vernon Winfrey, named for the barber, grocer and Metro councilmember. And yes, Oprah’s father, with whom she was sent to live as a teenager. She credits his emphasis on education and hard work for her early success, resulting in her landing a job on the radio as a teenager while still a student at the old East High School, before moving on to Tennessee State University and … well, everything else. The Winfrey shop — now owned by The Chicago Trust Co., whatever that is (wink wink) — is all brick and very 1990s. Just across the street, though, is the much more vintage Reed & Son’s barbershop, a sign reminding patrons that they want your head in their business.

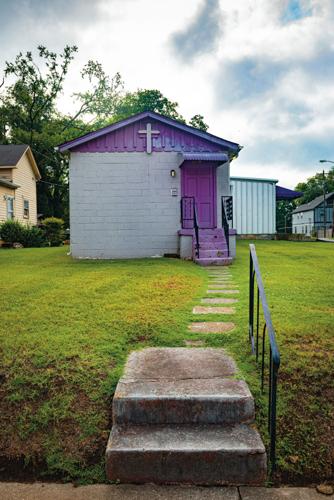

It’s decked out in whitewashed cinder block, trimmed in the traditional red, white and blue of the tonsorial artist. Catty-corner, another cinder-block building is home to the C.H.A.N.G.E. Ministry church. It’s mostly windowless, but painted in gray and muted purple.

Vernon Winfrey Avenue slides down into an intersection with Sixth at the edge of Cleveland Park, where the kids at the Boys & Girls Club would be happy to learn the sun has done its work and dried up the ball field.