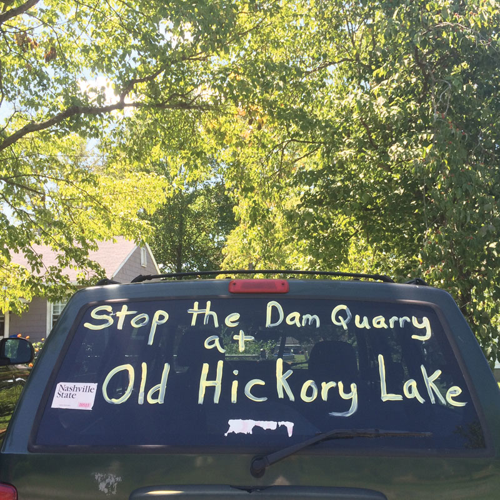

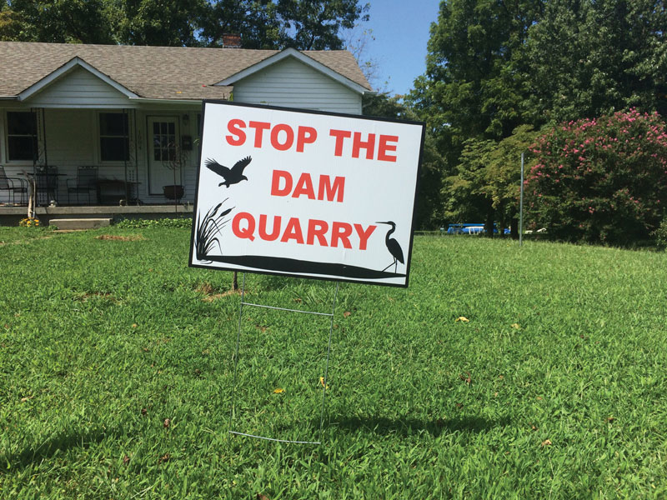

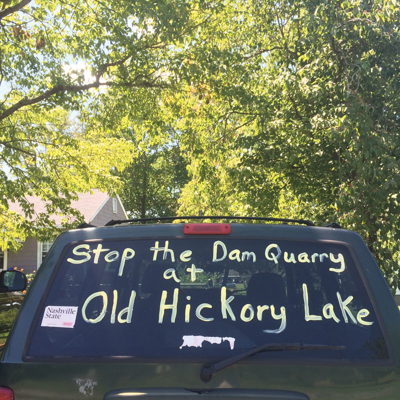

Cross the Old Hickory Bridge and drive through two neighborhoods on either side of the old Dupont munitions plant on the northeast border of Davidson County, and you'll find a campaign sign that far outnumbers those for mayoral candidates or Metro Council hopefuls. The message offers the combination of earnestness and subtle wit that any neighborhood protest movement requires: "Stop the Dam Quarry."

There's one in the window of Uncommon Grounds, a coffee shop in Old Hickory Village. There's one outside Skully's Saloon in Rayon City, and another in the yard of just about every house on Swinging Bridge Road, which runs alongside the site of the proposed rock quarry that has riled the area. The dam(n) thing would sit in close proximity to Old Hickory Dam, hence the slogan.

If these were the old days, some residents say, back when the Old Hickory community flexed more political muscle, there wouldn't be any need for signs.

The fight over the 141-acre piece of land is playing out on multiple fronts. Nearby residents say they're concerned about the value and condition of their homes. That's if the limestone quarry — and a possible concrete and asphalt plant — proceeds as planned, blasting deep into the ground across the street and trucking out the take.

But they're also worried about the ground itself. The site was occupied for decades by Dupont's gunpowder operation, after all. And just when the anti-quarry movement needed a boost, a bald eagle made a timely flyover, giving community advocates a new angle to explore: What about the environmental effect on wildlife? Might there be bats? Endangered bats? Don't forget the rumored sighting of monarch butterflies. Or the proposed quarry's proximity to a nearly 60-year-old dam.

The continuing flap has managed to engage the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Metro Traffic and Parking Commission. Some perspective is required.

"So here's the history," drawls Councilman Larry Hagar, the District 11 representative who was re-elected without opposition in last month's election. Hagar starts a story the way you do in an area that obsesses over historical awareness and preservation — with a biblical recitation of the relevant lineage.

The property in question, he explains, was originally owned by the Gleaves family. As the story goes, they acquired it via a land grant after the family's patriarch fought in the Battle of King's Mountain in the Revolutionary War. The family — whose cemetery is nearby — owned it until the early 1900s, Hagar says, when they sold it to Dupont. For decades, he concedes, the area has been zoned for industrial uses, including rock quarries.

The land is now owned by Industrial Land Developers LLC, which is pursuing plans for the quarry. Hagar describes it as a "shell company" whose generic name serves to veil plans for the site. He also speculates that the push forward with the quarry was timed to coincide with Metro elections and the end of a council term, when interference would be less likely. But when he learned of the company's plans, Hagar tried anyway.

"I think they were a little surprised I got my ordinance in as fast as I did," he says.

Because he couldn't legally take the industrial zoning out from under the company's feet, Hagar filed a bill in Metro Council that would add restrictions and effectively block the quarry. But he was forced to withdraw it last month on second reading, after several council members objected to a suspension of the rules that would've been necessary for the bill to go forward — and for a large group of assembled quarry opponents to address the council that night.

One of those objections came from Councilman Robert Duvall, a candidate in the at-large runoff who has been marked for defeat by an opposition Facebook group — No Quarry in Our Yard, which has more than 1,300 members. At a community meeting, with neighbors crowded into Uncommon Grounds last month, one resident called for a return to the days when "if you didn't carry Old Hickory, you didn't get elected." The group is evidently of the same mind, calling for opposition to Duvall while backing candidates such as Jason Holleman who have come to the neighborhood in support.

Hagar plans to refile the ordinance this month and attempt to get it approved by the new council. Until then, opponents are unashamedly seeking any bureaucratic obstacle possible that will slow down the project until he can do so.

Lucky for them, there are plenty. Among them: TDEC requires more information, including updated environmental assessments, before granting a permit for the company to discharge treated industrial storm water and wastewater into the Cumberland. And the Traffic and Parking Commission hasn't yet issued a required permit, out of concern for the roads' ability to handle the heavy traffic.

Tom White, the longtime land-use lawyer who typically appears as a reliable villain in such disputes — a Scene profile once named him "the developer's friend" — doesn't believe his clients will have a problem. Who are those clients? "A group of local businessmen" is all White will say. Documents related to the project list one W. Preston Murrey III as the company's president.

Regardless, White thinks it's an open-and-shut case. He even thinks the eagle is nesting out of range to do any good.

"I think it's very clear to everybody that there's a vested right by the client in the property for a rock quarry," he says. "I think what's also obvious is the property's been zoned IG, which is the heaviest industrial zoning in Davidson County, for more than 50 years."

Yet that first bit is not clear according to Hagar, who is also an attorney. He says he's not convinced that, under a new state law, the company is sufficiently legally vested in the property to be protected from new restrictions. The answer to that question could ultimately determine the legality of his ordinance.

White emphasizes that no public hearings were required for this project, but says he was the one who notified Hagar — with whom he says he's been friends for decades — about the company's plans. He also says the roads have always been used for industrial purposes, but that the company has agreed to a route that would avoid residential areas. At root, he says, the landowners have every right to do what they want with the property.

"I understand that there are legitimate concerns, and we're reaching out to people with respect to the issues and how we work through them," he says. "But it's there as a matter of right. It's not a neighborhood vote about whether or not you allow a quarry on this site. It's one that's been allowed for 50-plus years."

The neighborhood is still determined to fight it. Sitting on her front porch on Rayon Drive, about a mile from the would-be quarry site, where she's lived for five years, Kellye Branson details the renovations, finished and ongoing, to nearly every house immediately surrounding hers.

"It was kind of nice that prices are starting to rise on our street and, you know, once I paint my porch everything will be looking a little bit nicer," she says, laughing. "And then now we're talking about a quarry going in a mile away, with all of the traffic, the noise, the dust, whatever comes with the blasting that goes on."

Branson sees the quarry as a millstone around the neck of a neighborhood trying to stand. Hagar explains that while Bridgeway Avenue — around the block from Branson's home — was once a more vibrant main drag through Rayon City, it was cut off when Robinson Road was built, directing traffic around the neighborhood. The effect shows. Vacant or run-down buildings line the street.

Down the road, Cory Sharp is living at ground zero. He's directly across the street from the land where the quarry would sit. His yard has a "Stop the Dam Quarry" sign, right alongside one for Jason Holleman.

Sharp, a landscaping professional who studied agriculture in school, says he hates politics. But he has gone deep into the quarry fight, with a particular concern for preserving the environment it would displace. After work on a recent Monday afternoon, he leads a reporter into his house, offers a cold beer, and dives into stacks of documents he's downloaded from the TDEC website. It's a heap of material — issues about what's in the ground over there, concerns about nearby wetlands, details of all the various studies, assessments and questions about the project.

He acknowledges that this is, in a way, a typical episode of Not in My Backyard. But considering that this is where the Cumberland River enters Davidson County, and with the dam nearby, he says it's more than that.

"This is in everybody in Nashville's backyard," he says. "It's a lot more than just here."

He hops in his truck for a quick driving tour around the site, pulling over to note the wetlands. He points out the patch of trees where he says an eagle nests, just off site.

"I'm sick and tired of hearing, 'Sharp, you're dealing with people with a lot of money,' " he says. "That makes me want to fight them even more."