One warm night in February, a group of friends sit laughing, talking and clattering mugs in a cluster of upholstered armchairs at The Flying Saucer. It could be a scene from any Hollywood movie about a reunion of old friends, so comfortable and filled with inside jokes is the conversation. You'd never guess the nondescript group contains some of the best visual artists in Nashville.

The guy with the Buddy Holly horn-rims is Mark Hosford, whose old-timey fedora and protruding Adam's apple make him look like a black-and-white ad man. But the Vanderbilt professor is the only local artist represented in the Frist's current Fairy Tales, Monsters and the Genetic Imagination exhibit, and his work has been shown alongside the likes of Kiki Smith and Chuck Close. He'll be featured in another show at the Frist later this summer — just across the parking lot from where he's sitting.

Beside him is Hatch Show Print's Laura Baisden, who gives everyone high-fives and flits from conversation to conversation. She's as bright-eyed and effortlessly comfortable in this group as an extroverted kid sister; she also represents one of the most influential print shops in the country.

Also greeting people with hugs and warm enthusiasm is Bryce McCloud, whose Isle of Printing shop is drawing attention well beyond the city limits. He's just had to move into a larger space and retail outpost downtown, beside Hot Diggity Dog on Ewing just off Lafayette.

It's a close-knit group, and McCloud, who seems a kind of unofficial leader, has given it the tongue-in-cheek name The Mysterious Order of the Print. They laugh it off, but as more printmakers file in — forcing those gathered to move to a table, then to two tables, then three — it's clear something is happening beyond coincidence. As the group keeps expanding, a visitor notices the words Hosford has lettered Night of the Hunter-style across his knuckles: PRNT CLUB.

The printmaking explosion happening across the country, with Nashville as a vital part, is less an underground phenomenon than a movement hidden in plain sight. Like advertising, of which it is sometimes a subset, printmaking is so ubiquitous in our image-saturated landscape that some people don't even register it. And yet the blocky rough-hewn poster for a Ryman show, the antiquated intricacy of an Olive & Sinclair chocolate wrapper and the sly simplicity of T-shirts bearing the Third Man Records logo all spring from this small but growing group of friends.

Unlike other art movements, however, this one is inclusive rather than exclusive. To be sure, it has many variations of style, purpose and procedure. But its practitioners embrace each other as kindred spirits, rather than arguing over who does or doesn't belong. It has retained some of the band-of-outsiders ethos that once characterized punk and indie rock, two forces vital to the resurgence of print culture. It is cheap yet collectible, adventurous yet accessible, painstaking to produce yet immediate in impact. And it's invigorating the Nashville art scene like live current.

Arguably, printmaking is the people's art. For all the ways printmakers have incorporated digital advances, it remains much the same process that fifth-century Chinese woodcutters used. Whenever a band grinds out T-shirts, a kid mashes down a potato stamp, or a neighbor spray-paints yard-sale signs from a stencil, each is practicing an art that's survived for more than 15 centuries.

In its simplest terms, printmaking is the act of transferring ink onto a surface through some sort of "matrix" or mold. Most often the process involves letterpress (where a relief image coated in ink is pressed onto a surface, like a stamp), screenprinting (where ink is pushed through a stencil onto a surface), or etching (where a plate is created to hold ink in its crevices, with the raised portions remaining blank).

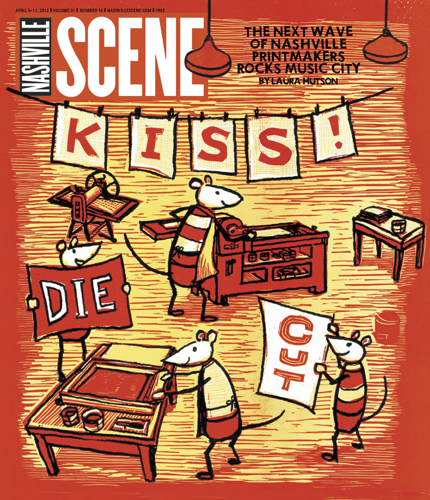

Within those broad parameters, all sorts of variables exist. So does a whole language of printmaking that's reminiscent of the slangy shorthand that once characterized greasy-spoon kitchens and other blue-collar workplaces. Examples include "furniture" (the blocks used in letterpress to take up space without transferring ink) and "ghosting" (a faint printed image that unintentionally appears on a printed sheet). For hard-boiled eloquence, it's tough to beat the term for cutting the top layer of a pressure-sensitive sheet and not the backing: "kiss die cut."

The rise of Pop Art and the counterculture in the 1960s brought a new appreciation for printmaking, especially the concert posters that proliferated in the age of psychedelia. In recent years, printmaking has seen a similar resurgence, not just as an art form, but as a valuable commodity. To collectors, a print is more affordable than a painting, while its handmade aesthetic offers a similar appeal.

That combination of artistry, accessibility and affordability has created something of a boom. It's been boosted by the popularity of Flatstock, a rock-poster convention established by the American Poster Institute in 2002. It's scheduled concurrently with Austin's SXSW every year, and it is proving as galvanizing an influence on printmaking culture as the surrounding festival has been on music and film. Perhaps more importantly, it has helped establish a printmaking network, a web of encouragement and creative exchange.

The nexus for Nashville printmaking is Hatch Show Print, the legendary shop that serves as the one degree of separation between many of the city's most talented print artists. Bryce McCloud worked there out of college in the late '90s; Laura Baisden, Brad Vetter and a handful of other talented printmakers are there now. Hosford grew up knowing about the famous printmaking shop, whose history dates back to 1879.

"Hatch has always been a feeding ground for printers who are learning to cut their chops," Hosford says.

Jim Sherraden — pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable, "like 'Aladdin,' " he instructs automatically — has been running Hatch Show Print since the early 1980s. No one is more aware of the space's historical value.

"These posters were meant to get you off the tractor and into the shows," Sherraden says, with a directness offset by his worn workboots and Wrangler jeans. Once he learns your name he repeats it throughout a conversation, a salesman's mnemonic trick put to good use.

Hatch's walls are papered with historic posters. The farther back you walk, the deeper you find yourself in the Hatch archives. Magicians, minstrels, vaudevillians — enormous posters of bygone acts line the walls, floor to ceiling. The inky sawdust smell fills the air like an antique fog.

Though it's a space that literally emanates history, Hatch is peopled with young artists. Bethany Taylor has long blond dreadlocks and uses a press to experiment with layers of woodgrain and ink colors to psychedelic effect. Vetter rides his bike to work every day — a sleek Italian Bianchi with a Brooks saddle. Yet they all share Sherraden's almost religious respect for the shop, and by extension, for Nashville's fabled history as an epicenter of print culture.

For all its branding as Music City, Nashville is arguably foremost a printing town. Its status as the hub of Christian publishing helped earn Nashville the nickname "the Protestant Vatican." It's a capital city with a history of important newspapers and two centuries of tumultuous journalism. At the center of this bustle was one of the flashiest spots in the city, Printers Alley.

Few know Printers Alley in anything other than its current incarnation as a tourist destination of karaoke bars, blues joints and topless clubs — a gleam of ersatz French Quarter decadence on the Bible Belt's buckle. But in the late 1800s it was a workingman's hub of ink-stained shirts and fingers. (People once casually referred to printing as "the black art" — not because of any nefarious implications, but because it would literally blacken workers.)

At the alley's industrial peak, Nashville could boast two large newspapers, 10 print shops and 13 publishers. The way Kentucky's coal mines and Detroit's automobile plants define their hometowns, the print industry defined Nashville for many years. Throughout that time, the people involved rarely considered themselves artists — they were just working stiffs. As Hatch's own homepage says, explaining why many historic posters are lost to the ages, "No one kept an archive, or 'copies,' of the jobs because for decades a letterpress poster was perceived as just a poster — nothing special, not a prize."

"I think it's a medium that was a craft for a long time, and people who did it focused on craft, not creativity," McCloud says. "The work could certainly be beautiful, but craft was paramount to the artist. It's like the act of making it is the art. Like a crazy Persian rug."

In the 19th century, printmaking was above all a way to reproduce paintings and ideas. In recent years, that way of thinking has subsided. The rise of printmaking as a creative art may have coincided with the decline of printmaking as a reproductive medium, but that didn't stop printmaking tools from becoming accessible to people who wanted to try them.

"A lot of really talented artists are using this as their medium," McCloud says, shrugging off larger claims for what's happening in Nashville printmaking. "That's indicative of the national movement."

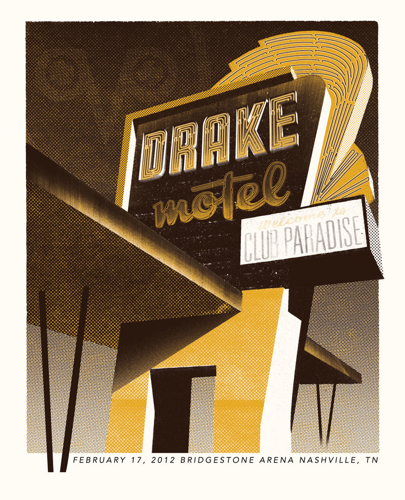

But one thing makes Nashville unusually fertile ground for the print revival, and it's there in the name "Music City." The thriving live music scene guarantees there will always be a vehicle for print art — gig posters.

"In the late 1800s Nashville was a print industry city, and then you have the music publishing industry," Hosford says. "So you have these two different forces of printing and artists, and they feed off each other."

Among those benefiting from Nashville's lively music scene is Andy Vastagh of Boss Construction, one of the city's most prolific gig-poster printers. On the day after this year's Flatstock convention has ended, he's trying to pin down an appointment to get a tattoo with the president of the American Poster Institute. They want matching tattoos of an eagle carrying a hoagie sandwich in its talons.

Memphian Vastagh graduated college in 2002. By 2005, CMT asked him to move to Nashville to work for them full time. He continued to freelance his own jobs on the side, and by 2008 he was able to focus on his own work. It's been good business for Vastagh, who speaks with the straight-faced confidence of someone proud of hard work.

"I liked the immediacy of creating a piece of art and not having to wait around for a gallery's approval," Vastagh says. "It's a little more instantly gratifying than waiting for someone to tell me it's good enough to show people."

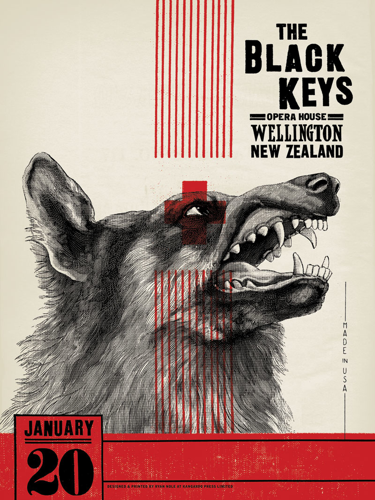

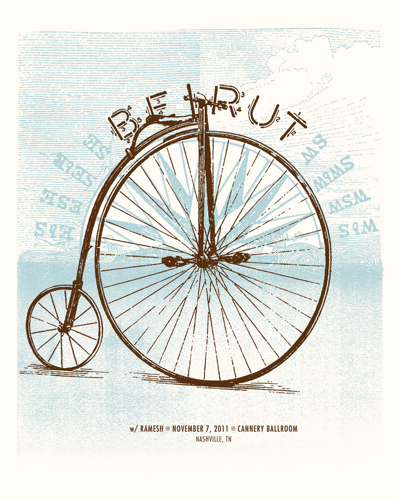

Vastagh's work reflects printmaking as a commercial endeavor. His designs are stylish, but more as a way to get his point across. He can reel off a laundry list of ideas that are trending: gemstones, praying skeletons, islands with something else beneath them, like a human head or a reflection of a pirate ship. He can also cite ideas that connect with certain audiences. For instance: Cactus or cow skulls sell well in Austin, bicycles do well in Chicago — and birds sell pretty much everywhere.

"The whole 'Put a bird on it' meme is definitely true in the print world," Vastagh says, "but you could also say 'Put an octopus on it,' or 'Put a bike on it.' " He grins like a magician who's just given away the tricks of his trade.

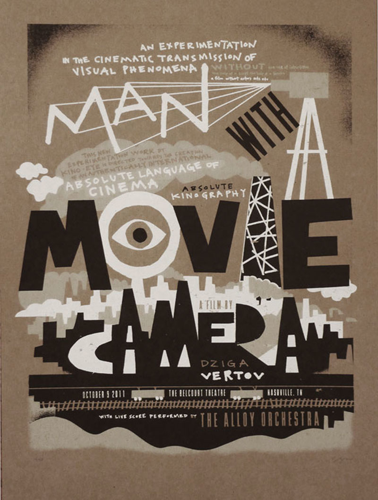

Another Nashville printmaker who tweaks the traditional gig-poster medium is Sam Smith. Though the native Nashvillian is a practicing musician — he's a drummer for both Ben Folds and My So-Called Band — his first love is film. He studied at New York University's prestigious film department, which boasts alumni such as Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee, and he's frequently seen taking in movies at The Belcourt.

"I try to bring local printing into the movie world," says the tall, baby-faced Smith, whose easygoing manner masks his creative ambition. "My philosophy is this: Seeing a movie with a certain group of people on a certain night can be a memorable experience that you will remember, just like a concert."

That has led Smith to design a series of posters to accompany Belcourt events such as the current Robert Bresson retrospective, the premiere of Harmony Korine's Trash Humpers and the Soviet silent Man With a Movie Camera. Smith says he got inspiration from Austin's Alamo Drafthouse, whose limited-edition poster runs have become instant sell-outs.

"They have a printing company called Mondo, and they've done projects for everything from Star Wars to Pixar," Smith says. "I did about eight or 10 examples really quickly, printed them out at Kinko's and brought them over to [Belcourt program director] Toby Leonard, and said, 'Look, this is what we can do.'

"We did posters for the Chaplin Film Festival, the Kurosawa Film Festival, the Film Noir Festival, and sometimes posters for midnight movies, like The Big Lebowski, which was very successful." He's now trying to interest The Belcourt in doing a monthly cult-movie series with a commemorative poster for each film.

Smith's most successful Belcourt print was the howling cat face he made for Japanese horror film Hausu (House). The piece not only became the cornerstone of arthouse titan Janus Films' successful national release for the film, it got Smith a second career designing movie posters for Janus and IFC Films as well as DVD covers for the prestigious Criterion Collection label. Ask him today about Hausu, however, and Smith brushes it off with a shrug and quickly changes the subject. In the printmaking world, permanence is rarely the goal — it is multiplicity and distribution, and you have to be able to move on.

If Andy Vastagh exemplifies the commercial side of printmaking, Mark Hosford holds up the fine-art end of the spectrum. The fact that their work overlaps so readily is a testament to printmaking's unpretentious origins in punchclock drudgery.

"Printmakers always have a sense of being the underdog of the art world," he says. As a result, there is astoundingly little ego involved in the printmaking community, and appreciation for each other's work exists across the board.

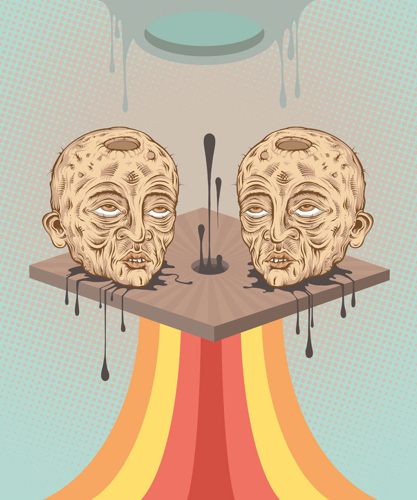

It helps that they borrow a lot from the same inspirations. Hosford's office is a cacophony of Mark Ryden and Francisco Goya, and he doesn't apologize for the lowbrow-highbrow mash-up of his influences.

"I like tattoo images and horror and comic book imagery merged with history prints merged with contemporary drawing styles," Hosford says. "And I like to be able to draw things that sometimes seem inane merged with real intelligent things. But because the prints are done in such an immaculate, technical way, if I draw something that seems like black humor and somewhat cartoonish, the sheer intensity of the technical way it's done outweighs that and brings it to a new level."

If Hosford's influences include a storehouse of what's often demeaned as junk culture, Lesley Patterson-Marx uses her prints to incorporate and transform something closer to a thrifty Depression-era mom's bag of scraps. Though the former Watkins printmaking teacher is as much an exemplar of printing-as-fine-art as Hosford, her work amounts to a patchwork quilt of ephemera.

Old photographs, vintage wallpaper, stamps, plants and insects all find a place in the early stages of her prints. She then uses a solar process to turn her collages into several plates, each one assigned a different color. Then she uses a plastic knife to mix intaglio inks on her glass tabletop, pouring blues and reds and whites until she gets it just right.

"I treat printmaking as an extension of collage," says Patterson-Marx, who now helps run the Platetone Printshop in West Nashville. "I consider myself a mixed-media printmaker."

She has crisp blue eyes and baby-doll features punctuated by half-moon eyebrows, and she wears a pretty denim apron made by women in the Dominican Republic when she works. She listens to AM radio in her studio as she weds unconventional processes to traditional techniques, resulting in tiny books about her grandmother that are bound with black bobby-pins, small prints based on antique photographs, and shadowy curios fashioned by photo-emulsion legerdemain out of four-leaf clovers.

"I feel very connected to technology in this process, even though my work is so nostalgic," she says, noting that she uses nontoxic ink to increase the longevity of her printmaking career. If she treats printmaking like collage, she treats collage like alchemy.

"Layers imply time, and I like the idea of things with a process to them," Patterson-Marx says. "I like seeing things change and transform."

That's one of the most interesting contradictions in the printmaking genre. The traditional tools are cumbersome, and equipment is heavy and difficult to move — yet the products they disseminate are rarely meant to last. Bryce McCloud knows this well. He inherited his letterpress equipment from his uncle, Tennessee historian Roger Firth.

"My uncle was the curator of industrial technology at the State Museum," McCloud says softly, in his gentle drawl. "He discovered letterpress printing and just fell in love with it. He was studying during the transitional period when the trade was dropping letterpress printing, and all the people who were doing it were retiring or dying, all their stuff was being thrown away.

"People didn't value the equipment. It wasn't hip. It was the '80s, and printing was yesterday's news. It was just an industrial technology, and they'd come up with new ways to do it faster — like Xeroxes. Nobody thought about it as an art form. It was a means to an end, like steam locomotives."

Although McCloud wears Oxford-cloth shirts and good jeans, his messy hair matches his boyish enthusiasm for his work. He rides a Russian motorbike to his Isle of Printing studio in South Nashville, and he freely offers rides (he keeps a spare helmet in the sidecar). His studio is a minefield of shiny vintage equipment so huge it could crush you if it tipped over during a move.

"My uncle passed away, and I took over the equipment," McCloud says. "Sometimes I look at it all and think, 'One day this will all be someone else's.' It's a gift, and it's also an enormous problem. There's a real sense of love in this equipment. I've invested a lot of my life into protecting this stuff, and it's become my whole reality — I can't just pack up and move without leaving all this stuff behind."

"A lot of my life has turned into being the caretaker of this stuff. I feel like it shapes my life as much as I do. A lot of people want to have this equipment, but it isn't a casual affair. It's like getting married."

McCloud used to share a space with Ryan Nole, a printmaker who now runs his own nearby studio, Kangaroo Press. Nole moved to Nashville from Bloomington, Ind., about four years ago, and since then he has become one of the city's most sought-after printers. On one day in March, he was working on jobs for Imogene + Willie, Crema and 12 South Taproom.

Nole has the rectangular glasses and deadpan delivery of David Cross, and the hallway that leads to his shop is lined with framed posters he's made for bands like Built To Spill, Guided By Voices and Modest Mouse. His studio is a mixture of old and new technology, of antique letterpress machines and a six-legged automatic T-shirt press, of vintage Coke bottles and Goonies pinball machines.

He's using the spidery T-shirt machine to print 12 South Taproom logos onto bright red tanktops in one room. In another, his old Heidelberg letterpress is printing labels for Crema coffee. The Heidelberg, Nole says, was made in 1965. "They call it a windmill because of the way the arms hold the paper," he says, cleaning a plate with mineral spirits that he keeps in an old whisky bottle.

An hour later, Nole has printed a couple hundred labels for Crema, but not after fastidiously mixing ink to just the right color, measuring and remeasuring the spaces until everything's dead center. As he works he explains his process, punctuating certain steps with, "If I really want to get anal, which I usually do." It's amazing how specific these massive machines can be in the right hands.

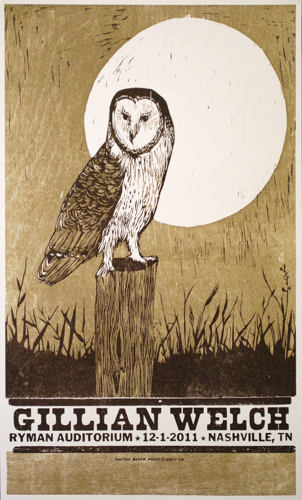

The differences between Nashville's printmakers are broad enough that their similarities stand out in contrast, the most obvious one being: They have extraordinarily good taste and conceptual skills. Baisden, for example, imagined Gillian Welch's music as a sad/sweet owl on a fencepost for a poster advertising her Ryman show. Welch now requests that Baisden handle all her posters. McCloud can put Fred Rogers and Johnny Cash on paper pennants, and the imagined correspondence between the two is enough to bring even the most cynical of us close to tears.

Almost more than fine artists, printmakers are responsible for understanding the needs and desires of their culture. That often means knowing what people want to see before they know it themselves. As a result, printmakers are instinctive hoarders of the popular imagination, scouring ideas from sources as obscure and disparate as vintage Sears catalog ads, Soviet movie stills, Edwardian children's-book illustrations and Norwegian postage stamps. Nole collects vintage stuffed animals that are straight out of Mike Kelley photographs, and even the Johnson & Johnson baby powder he uses on his machine comes in a Chinese package.

But there's something inherently down-to-earth about printmaking. The same process that has been used since Printers Alley teemed with ink-stained workers is essentially the same as that espoused by Rembrandt and Goya — which Nole now uses to make T-shirts for Third Man.

"There's an accessibility to printmaking," says Hosford, "and it's a perfect bridge between mass-produced and unique. I think we've reached a breaking point, and we're getting away from mass marketing. The physical nature of the object is what's important — like buying and collecting vinyl records."

A common thread among many printmakers seems to be that they begin with another medium in mind — some type of art with a capital A — but move on to printmaking for whatever reason. Hosford says he sees that often in his students, who sometimes start a class not knowing anything about printing. By semester's end, they're converts.

"I feel like I'm almost like a preacher who wants to bring the gospel to everybody," Hosford says. "Printing has transformed me so much that I feel like I need to share it."

Although his uncle was heavily involved in letterpress, McCloud was fairly unaware he could adopt the medium as an art form. The moment he embraced it, his life changed.

"I studied sculpture in college, and was making these big monstrosities out of concrete and metal, and they felt really permanent — and completely immovable," he says. "I remember dragging some of that stuff home from college, and it was just completely ridiculous. It kind of becomes this albatross around your neck, because what do you do with it?

"But prints!" His eyes light up, and you can imagine a light bulb blinking on in his head back in his college days. "A print is so easy to distribute, it can go anywhere. You can make something today, and tomorrow it can be to China. And there would be no crane involved, no shipping container.

"It makes it easy to share. And that's what I really like about printmaking."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.