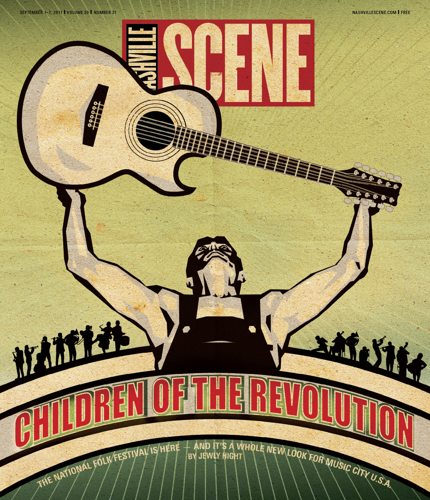

The press kit for the National Folk Festival contains a ringing endorsement of its mission from the president of the United States. Yes, when the event arrives this weekend in Nashville, which beat out 43 other cities to host it, it will carry the approval of the commander-in-chief in office during its earliest years — President Franklin D. Roosevelt. (The first National, as it's called for short, was held in St. Louis in 1934.)

As public relations go, that's a sizable score. Add to that the fact that first lady Eleanor Roosevelt served on one of the festival's committees — as did a pre-White House Harry Truman, novelist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston and the venerable poet James Weldon Johnson, to name just a few — and you've only scratched the surface of why the National, now approaching its eighth decade, may be the most the most historically significant, culturally rich music festival most people have never heard of.

Not to mention one of the most inclusive. It's not particularly groundbreaking for a festival to take a melting-pot approach now: That's status quo at Bonnaroo. But folklorist Sarah Gertrude Knott founded her traveling folk festival in a very different world. In the 1930s, mono-cultural folk fests were the norm — some established by purists who saw it as their duty to keep Anglo-American folk culture unsullied by anything as funky or exotic as African or Native American influence.

So it's no small thing that the National cultivated diversity from the start. In 1936, Knott and her team dared integrate their stage in segregated Dallas. Two years later, the festival welcomed uptown African-American bluesman W.C. Handy to a Washington, D.C., venue owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution — one that explicitly prohibited black performers.

Now the National is coming to Nashville for a three-year stay in Bicentennial Park, culminating in the celebration of the festival's 75th edition. At first glance, it may seem an odd pairing of event and host city: a multiethnic showcase that was once ill at ease with commercial music, in a city that's recognized more for its music industry than for its embrace of ethnic diversity.

"Because Nashville's already known for its music focus and many musical events, it did surprise people," says Julia Olin, executive director of the National Council for the Traditional Arts.

But now it's Nashville's turn to be surprised — by an event that offers dozens of diverse, dynamic, anything-but-dry cultural performances. A great deal of thought goes into the festival, but it's no academic exercise. When these bands play hot dance music, audiences actually dance.

Better still, the spirit of cultural ambassadorship runs both ways. According to published estimates, previous fests in cities such as Chattanooga have drawn as many as 90,000 people. As hometown folks and visitors to Music City work up a sweat to a top-notch band from another part of the country, playing a style of music from another part of the world, the hope is that they will come away with a new appreciation for Nashville's own cultural riches.

This will not be the first Nashville visit for the National, though memories of it are understandably scarce. The only other time was in 1959, back when founder Knott and her collaborators still populated the bill with nonprofessional, unpaid performers. Anyone who attended the five-day event at the Fairgrounds Coliseum would have seen war-dancing Kiowa Indians, shape note singers, a band of Wisconsin lumberjacks, a Scottish-style high school drum corps, square-dancing 4-H kids, African-American singers of spirituals from Agricultural and Industrial State University (Tennessee State University to us), Mexican folk dancers, fiddlers and myriad other offerings.

Conspicuously absent, though, were the pickers and singers who cut commercial records and entertained on the Opry. (An exception that proved the rule was guitar-playing folk balladeer Jimmy Driftwood.) In Staging Tradition, Michael Ann Williams noted, "Although located at ground zero of the country music industry, Knott found few native singers in Nashville."

A lack of native singing didn't mean a lack of rootsy talent. Back then, folklorists tended to draw an artificial line between hillbilly and folk music. Anybody who made a living as a hillbilly entertainer, the reasoning went, couldn't possibly qualify as an "authentic" folk singer.

But in the 52 years since the National was last here, a lot has changed about how we think and talk about folk music — the way its sounds travel, its coziness with pop culture, and what constitutes folk tradition in an age when households are infinitely more plugged in than they were even in the days of family radio.

By the time the urban folk revival reached its zenith in the early '60s, hordes of college-age idealists had adopted folk music as their own. They gathered around their own youthful revivalist stars, like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, and then-new folk festivals like Newport. At the time of the first National, neither Dylan nor Baez had even been born.

The National — which invited precious few big-name revivalists — had a hard time bridging the generation gap. For a few short years in the early '70s, following Knott's retirement, the National Park Service ran the festival in a similar manner to Newport. After it changed hands again, things circled back around to an updated version of Knott's tradition-centric model — only this one allowed paid performers.

As the festival embraced professional folk artists, new-breed folk was changing Music Row. A singer-songwriter scene sprouted in Nashville, first with guys like Tom T. Hall and Kris Kristofferson, then Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt, with others to follow. Emboldened by the freewheelin' Bob Dylan and his folk-revivalist counterparts, they placed emphasis on having something smart to say and an original way to say it, expanding the language of country music in the process.

A barn-shaped Nashville landmark embodied an even more profound paradigm shift in folk-versus-country thinking. When the original Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum opened its doors in 1967, it expressly laid out the folk roots underpinning country music's commercial success. No longer could country be dismissed as cultureless. As Diane Pecknold put it in The Selling Sound, "cultural power and cultural authority were fused in a single voice."

It's only fitting, then, that the Hall of Fame and Museum is curating part of the Tennessee Folklife section of the festival, and in that context, taking a folkloric approach to the history of Nashville's music business. Says vice president of museum programming Jay Orr, "We really see country music as a commercial art form that has deep, deep connections to tradition."

[page]

Even though the urban folk revival is ancient history — Dylan just turned 70, after all — people still tend to associate folk festivals with guitar-toting folksingers. But you won't find them at the National Folk Festival. It's a dynamic celebration of diverse performance.

As unwieldy a concept as "folk" can be, it's not at all hard to get an articulate explanation of what the festival looks for in a performer: someone who puts on a phenomenal show and doesn't work in a bubble.

"We are the National Council for the Traditional Arts," says programming director Joshua Kohn, "so we really try to represent the highest quality and most connected of the tradition-bearers that we're working with.

"But that can't be the complete story. Because there's a lot of people and a lot of artists out there who maybe their specific story is really compelling, but ... what they are onstage, is not as compelling. So we want to make sure that every artist we work with at the festival is of the highest quality ... that when an audience sees them, it's going to be a startling experience for both audience and artist alike. ...We're not just going to book any electric blues group out there."

As for what the NCTA counts as traditional, Kohn explains, "Tradition is always evolving. And if we didn't evolve with it, if we didn't evolve our definition, then we would be stuck with a really boring festival, to be honest — with people who consider themselves part of a tradition, but who are no longer supported by that community, or their art form isn't as vital anymore.

"Something like break dance — all forms of urban dance — are continually evolving, but are still held within this very tight-knit community. They speak to each other and they work with each other, inasmuch as you find the banjo and fiddle and old-time communities in Appalachia speaking and working with each other. And to us that's very exciting."

The break-dance allusion isn't a theoretical example. This year's festival features the Seattle B-Boy/B-Girl crew Massive Monkees. They made it to the final three on Season 4 of MTV's America's Best Dance Crew and travel the world competing, plus they've shared the stage with Jay-Z and done Xbox ads. But they're also regulars at their local after-school programs and community centers, the same sorts of places where they started learning their moves as teenagers.

Founding member Brysen Angeles runs down the genealogy: "We all started congregating at the same community center, and the thing that was bringing us there was the dance and the hip-hop. There's an older generation of guys; there's a group called BOSS and there's another group called DVS. So they became kind of our mentors and taught us what the culture's about and what hip-hop's about, and really what they preached to us was the foundation of the dance, the root of where the dance style came from. They also taught us to be giving with the dance. ... So I guess along with that comes the willingness to share it when you get a little bit older."

In other words, square-dancing has nothing on the handed-down folk pedigree of the Monkees' hip-hop acrobatics, even if break-dancing sells ads on MTV and isn't the slightest bit rural. There's another hotly anticipated act playing this year's National that comes from a similarly urban and decidely contemporary community.

That would be the Latino ensemble La Excelencia. Its members have given spandex-clad Zumba enthusiasts everywhere something to shake it to, but the band's home turf is the club scene of New York. They play salsa dura, which co-founder and percussionist Jose Vazquez-Cofresi translates as "hardcore salsa."

The members of La Excelencia consciously distance themselves from the big-selling sentimental pop balladry (think Marc Anthony) that dominated salsa throughout the 1980s and '90s. Instead, they reach back to salsa's Afro-Cuban roots with their robust rhythmic attack and punchy horn-playing.

"If we were a rock band," Vazquez-Cofresi says, "we'd be heavy metal."

They've ruffled feathers by wearing their street clothes on stage — baggy jeans, jerseys, baseball caps — as opposed to the identical suits the old guard expects from a salsa band. And instead of singing about romance, their repertoire of originals is political, intelligent and gutsy. They talk about the immigrant experience, economic inequality, things that feel relevant to their community.

"We may be modern in the way that we dress and the lyrics that we sing," Vazquez-Cofresi says, "but ... we go back as far as son, you know, the Afro-Cuban roots of this music. ... New York gave the birth of salsa in the '70s, but it was a fusion. It was a fusion of Cuban music, Puerto Rican music, a little bit of everything in between, including rock. So we've kind of just brought that back." The fact that what they're doing appeals to both their peers and a lot of other folks is a sure sign they're onto something.

"A lot of the older generation comes and hears us," Vazques-Cofresi says, "and they say, 'Wow, man! You guys make me feel like I'm 14, 15 sneaking into a club again. I haven't heard a band like this in so many years.' "

That said, there is no such thing as a main stage or a headliner at the National. In this thoroughly egalitarian setting, La Excelencia and Massive Monkees will do their thing alongside acts that contemporary eyes and ears would immediately identify as folky. It's not only an entertaining mix; it's realistic. Those performers who have more obvious ties to tradition are hardly insulated from pop culture, even if they are from up in the hills.

Take the acclaimed Holmes Brothers, an electric gospel-blues trio made up of Sherman and Wendell Holmes and drummer Popsy Dixon. (All three sing.) They have a distinctively ragged, soulful sound and a half-century history with music to boot. But their repertoire ranges from generations-old spirituals to an anthemic reading of Tom Waits' "Train Song."

Or consider Dale Ann Bradley, one of the finest traditional singers in contemporary bluegrass. Bradley had the sort of rustic Kentucky upbringing — without modern conveniences like electricity — that you'd associate with somebody much older. Yet her songbook contains room for a stirring breakneck version of U2's "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For."

Meanwhile, Ben Hall — fresh out of Belmont and also booked at the National — plays a kind of guitar you wouldn't expect to hear from somebody so young. He's an impressive, knowledgeable and tradition-conscious Merle Travis-style thumb-picker, even though he's generations removed from the guy who did more than anyone else to popularize thumb-picking worldwide, Chet Atkins. Hall started out listening to his dad's country reel-to-reels, but by his early teens he was immersing himself in the thumb-picking festival scene and learning firsthand from old-timers like Comer "Moon" Mullins.

"I'd put on the headphones up to that point, and I was curious about who these people were doing these things," Hall says. "But finally this gracious gentleman sat down and said, 'I think you've got some potential here playing this style.' That's when I put my focus on that particular thing ... and kept it there for several years."

Hall will share the stage with another thumb-style player he holds in high esteem, Eddie Pennington, who hails from Travis territory in Western Kentucky. On a high-school trip to Washington, D.C., Hall was elated to find a Pennington CD in the Smithsonian gift shop.

"I can't explain to you how that made me feel," Hall says, eloquently summing up the value of preserving the folk tradition. "For once my musical style has been validated. Right exactly where I wanted it to be validated — not on the hit charts, but in the Smithsonian."

The National is meant to lay the groundwork for an ongoing festival in Nashville. To say it will be joining a crowded field is stating the obvious. Every year there's Bluegrass Fan Fest, which Bradley has frequently played; the Americana Music Festival, at which Hall's late boss Charlie Louvin appeared; SoundLand, the new incarnation of Next Big Nashville; and the granddaddy of them all, CMA Fest. Which raises a good question: Why in the world does Nashville need another music festival?

Garry West, who, along with his banjo virtuoso wife Alison Brown, heads Compass Records and Nashville Folk and Roots — a new nonprofit that's serving as the NCTA's local partner — doesn't downplay the number of existing music gatherings in Nashville. But he emphasizes the differences between the National and the rest.

"[The others] seem to be sort of built for the industry, and they welcome the general public," West says. "This is built for the general public — and we welcome the industry, of course. But it's built for the general public and it needs to represent the general public as it exists in the community, not just what any one person's perception of it is in the community."

The general public doesn't even need to buy a wristband to get in; it's free. And since it's a free arts event — not federally funded and new to most of the big check-writers in town — raising the cash to pull it off has been the challenge anybody would expect it to be.

But Mayor Karl Dean, who has given the festival an FDR-style blessing locally, believes it has the potential to be a unique cross-cultural civic attraction.

"My hope is that it appeals to all Nashvillians — underline all — in a way that no festival we've ever done has," Dean says. "Showing off Nashville as Music City is something we can do easily, and we do it a lot. Showing off our diversity and the way the city has progressed is a harder thing to do, but I think it's a good thing to do."

It's hard partly because Nashville hasn't fully come to terms with its own diversity, as evidenced by some Nashvillians' anxiety over the presence of undocumented immigrants. But Dean — who's been a friend to immigrants and live music alike — sees evidence of progress in various quarters, among them Nashville voters' rejection of the so-called English Only proposition in 2009.

"If we had lost that English Only vote, it would be an interesting question of whether [the festival] would have come to Nashville," Dean says.

All these considerations shaped the pitch to the NCTA. "We really talked to them a lot about our perceived need for Nashville to understand itself as it is today, not as it was 30 years ago," Compass' Alison Brown says. "Because I understand according to Forbes magazine, we have the fastest-growing immigrant population in the country here in Nashville. So how do we represent the diverse demographic of the city? And what better way to do that than through music?"

The NCTA took the lead in choosing the performers, but only after a good bit of conversation with a local programming committee and various ethnic communities in Nashville. "The idea being that, first of all, we want to create an inclusive festival that is obviously welcoming to many different cultural communities," Olin says. "And then it's also about learning what hidden gems may be within the Nashville community that have not received very much public attention. ... It's an ongoing process where you can never accomplish those sorts of goals in one year."

With Nashville's Hispanic communities in mind, they've booked not only La Excelencia, but the world-class Mexican mariachi band Mariachi Los Camperos de Nati Cano. To acknowledge the city's sizable Kurdish population, they've invited the Bong Ensemble, an Iranian Kurdish and Persian quartet, to play with Özden Öztoprak, a Kurdish virtuoso from Turkey who now calls the Bay Area home.

Also, the Chinese Arts Alliance of Nashville is sending Chinese lion dancers. And at the request of the Japanese community, the duo Oyama x Nitta are on the bill. They're virtuosos of the shamisen — sort of a three-string banjo — who have a virile, shape-shifting approach to their instrument that can, at moments, bring to mind Led Zeppelin.

[page]

As for local treasures, there's Memphis-born Reverend John Wilkins, a gifted guitar evangelist like his father Robert Wilkins before him; Murfreesboro buck dancer Thomas Maupin, who just received a Folklife Heritage Award from Gov. Bill Haslam; and Aubrey Ghent, one of the world's premier steel guitarists in the hybrid blues-and-gospel-fusing style known as Sacred Steel.

A fervent playing tradition that developed in the African-American Pentecostal denomination House of God and thrives there today, Sacred Steel is a prime example of a a long-standing folk tradition only recently recognized by those outside it. Before folklorists became aware of it in the mid-'90s, Ghent chuckles, "Well, it had no real name. ... Basically we called it 'church music.' "

Ghent moved to Nashville 11 years ago, thinking the city's familiarity with country-style steel guitar would work in his favor. And yet for the most part, he and his playing have unjustly remained under the radar in these parts. The National will be the biggest gig he's played here, aside from sitting in with Robert Randolph, the Bonnaroo favorite who has brought Sacred Steel its primary brush with the mainstream.

"There's so many that haven't heard it," Ghent says. "When folks do hear it, they think it's a new style, a new trend. But as far as the church and the parishioners of the church, it's really an old style."

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum — along with Evan Hatch, folklorist of the Arts Center of Cannon County — is casting an equally purposeful spotlight on music business history under the banner of Tennessee Folklife. Don't expect handicrafts in the Hatch-curated demonstration area. What you'll find instead are exhibits on Hatch Show Print (no relation to Evan Hatch, for the record) and United Record Pressing.

"We're going to have an ultra-modern tour bus ... with all of the bunk beds and sometimes marble floors," Hatch says. "And that's going to stand in direct contrast with the Flatt & Scruggs bus, which in its day was quite nice. ... So we're going to have those set up as bookends so that people can see how Flatt & Scruggs traveled versus how, you know, Brad Paisley travels."

Drawing on its formidable Rolodex, the Hall of Fame is presenting panels on a number of Nashville-centric subjects, among them old-time singing, fiddling, black and white gospel traditions, family bands and Jefferson Street's R&B scene. Other panels will discuss the inner workings of the pre-'70s music industry, including sponsored radio shows and session work. That's a different take on folklife.

"With the studio musicians," says Orr, "what we're asking them to do is a little different than what they're accustomed to doing, I think. ... For the folk festival, we're going to talk a little bit more about session musicians as occupational folklife, talk about superstitions and rituals of studio musicians."

To Orr, there's an element of advocacy involved in giving a platform to people such as Nashville Blues Queen Marion James, Patsy and Donna Stoneman of the old-timey Stoneman Family, A-Team session legend Harold Bradley and gospel giants the Fairfield Four.

"By presenting them under the banner of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, and under the banner of the National Council for the Traditional Arts and National Folk Festival, I hope that that validates what they do and what they have done and their perspective on culture," Orr says. "I hope that it says, 'These people are important; these people have done things that are important; these people are worth listening to and watching and thinking about, and their art lives on.' "

Therefore, for Music City to welcome the only multicultural folk festival in the U.S. that's been going since the Great Depression isn't a case of, "If you build it, the cultural capital will come." It's more like, "If you build it, the cultural capital that's here already will come into view."

The National Folk Festival's Nashville tenure is a big deal for everyone involved. It has the potential to help get the festival higher on the radar once again, to change the way locals and non-locals alike look at Music City, and to give the tens of thousands of people who'll swarm Bicentennial Park this Labor Day weekend a broader idea of music and American life than they'd ever imagined. That, and a damn good time.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.