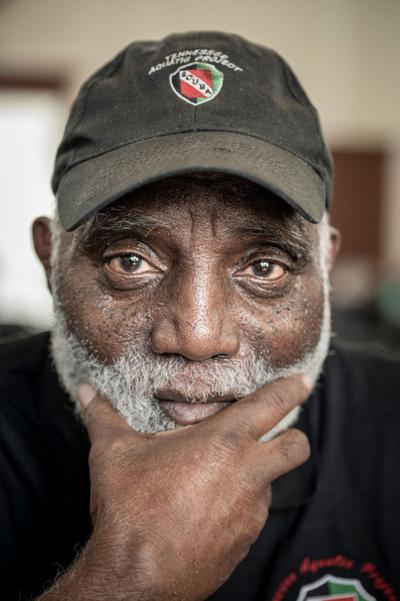

Ken Stewart

In 2004, Ken Stewart took a 35-mile boat journey to visit and clean the Henrietta Marie monument. The underwater monument, which lies close to the wreck of the slave ship Henrietta Marie off the coast of Florida, is dedicated to the memory of African victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The GPS device used to navigate gave the divers only a rough approximation of the ship’s location. “They finally found the monument,” says Stewart. “But the current was so strong that they had to put ropes down.” Stewart first learned to scuba dive in 1989, and he’d done countless dives before his 2004 journey. But the long dive and strong current made him nervous.

Luckily he wasn’t alone. He’d been mentoring young people in diving, marine archaeology and leadership skills for years, and some of his students were on the boat with him. “I kind of turned my back, and the next thing I know, they’re in the water.” As soon as they hit the water, Stewart says he thought, “Don’t stop.”

The dive to the Henrietta Marie is just one part of Stewart’s legacy cataloging the wrecks of slave ships and connecting traditionally disenfranchised groups to scuba diving and marine archaeology. Through two flagship programs — Diving With a Purpose and the Tennessee Aquatics Project — he’s helped keep Black history alive for countless people.

Stewart founded Diving With a Purpose in 2003 after meeting maritime archaeologist Brenda Lanzendorf through a documentary about the search for the slave ship Guerrero. Scuba divers always dive with an underwater “buddy” to ensure their safety; Lanzendorf couldn’t dive alone. Stewart sent out an email to some members of the National Association of Black Divers. “Tired of the same old dives?” he asked. “Let’s dive with a purpose.”

Since then, Diving With a Purpose has helped record and preserve countless underwater sites, with a particular emphasis on African slave trade shipwrecks. They’ve trained more than 500 individuals in marine archaeology skills using a five-day intensive course aimed at experienced divers. DWP also has a marine conservation training program and a youth program called Youth Diving With a Purpose.

Stewart helps people closer to home too. Since 1999, he’s run a life skills and leadership program for young people in Nashville called the Tennessee Aquatic Project. TAP is open to anyone ages 8 to 18 and particularly attracts young Black students, who make up around 90 percent of the program. The program offers everything from beginner swim lessons to Master Scuba Diver credentials, the highest level of scuba diving certification. Outside the pool, students must complete 20 hours of community service every year, maintain at least a C average in school, and complete TAP’s wilderness survival course. But most significantly, the program helps students grow. “Character is the most important thing to me,” Stewart says.

TAP funds activities for students who need financial assistance, with help from grants and a partnership with Metro Parks. Many teenagers in the program receive lifeguard certification, and every year Stewart takes students on a scuba trip.

Stewart is constantly setting new initiatives in motion. He’s set up YDWP chapters in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana and Honduras. He recently met with the descendants of victims of a wreck he helped catalog, and he’s currently teaching some slightly reluctant TAP students a photography class to give them a record of their lives as young people.

His work recording wrecks is always urgent, facing the pressure of seawater degradation and a federal government currently bent on erasing African American history. But Stewart remains determined. He puts it simply when speaking about each initiative: “I had an idea, and then I made it happen.”

His legacy has taken on a life of its own, with former students becoming conservationists, marine archaeologists, researchers and more. It was these students who led Stewart into the water at the Henrietta Marie in 2004, down to a monument to the 12 million enslaved Africans who crossed the Atlantic. As his young protégés led him down into the water and cleaned the monument, Stewart could feel the weight of history and the importance of their work.

Seeing the monument, he says, “It felt like the ancestors were with me.”

Our profiles of some of Nashville’s most interesting people, from a queen of Appalachian character comedy to a Vanderbilt football star, a 'Survivor' runner-up and more