There’s a Nashville Sounds billboard on I-24, just as you enter town. On it, two players stand side by side in crisp modern uniforms. Underneath them is the club’s new tagline: “Nashville Sounds remastered.”

These are the remastered Sounds — hip uniforms, at home in a beautiful new ballpark full of amenities. Come to First Tennessee Park for the baseball, stay for the miniature golf and the artisanal food. Or is it the other way around?

It’s all quite slick. Even so, I miss the old, un-remastered, untouched, analog Nashville Sounds, with all of their clicks and pops and imperfections. I miss players like Skeeter Barnes, and the cheerleaders, called the Soundettes. I miss the tiny baseball helmets full of soft-serve ice cream. I miss the total lack of self-awareness — or perhaps it was total self-awareness, come to think of it — that leads a baseball team to make a mustachioed man swinging an acoustic guitar its official logo. (His name was “Slugger,” by the way.)

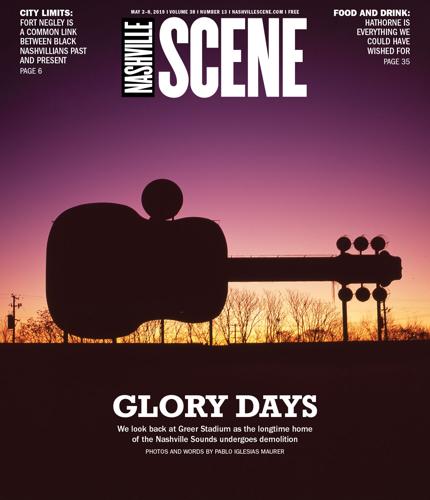

What I miss most of all is Greer Stadium.

Without Larry Schmittou — and Conway Twitty — the Nashville Sounds and Greer Stadium never would’ve come to be.

Schmittou was a former Metro schoolteacher and the head coach of Vanderbilt University’s baseball team from 1968-1978. He was tired of the grind and wanted his own club. In Twitty, a Music Row icon with a flair for self-promotion, he found an ideal business partner. The two, along with a handful of other country artists including the great Jerry Reed, purchased a minor-league franchise.

Funding the team was the easy part. Building the stadium would prove tougher. Schmittou reached out to local suppliers, who donated construction materials in return for advertising space. He took out a $30,000 personal loan. When that money ran out, he mortgaged his house.

Just days before the park’s first game in April 1978, the outfield sod showed up on a truck. It was dead. In a panic, Schmittou ordered another batch, and with the help of a few Sounds employees, invited the general public to a “sod party.” Early in the morning of the home opener, dozens of people showed up and threw down the outfield grass.

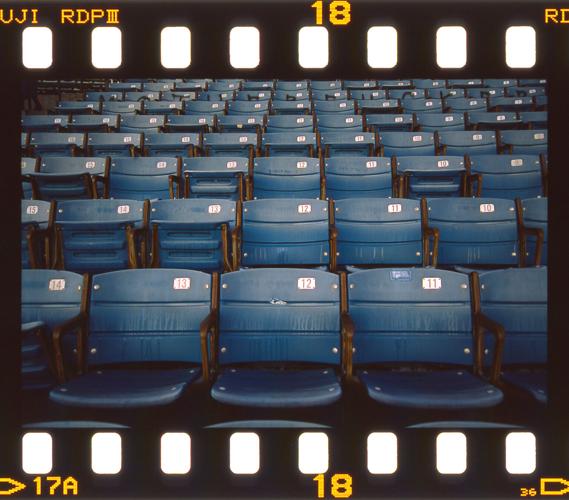

For quite a while, the Sounds were the hottest ticket in town. By the time I arrived at Greer Stadium in 1994 in search of a summer job, that interest had cooled, and Greer had begun to show its age. A Sounds game was no longer a happening.

But to a 14-year-old, it was paradise. The place proved an ideal escape from my life as an awkward, chubby teenager — an escape from cruel classmates and an older brother. For two summers, I worked every home game manning The Bullpen, a souvenir shop under the first-base grandstand.

I’d grown up in Boston, going to Red Sox games at Fenway Park, idolizing the likes of Wade Boggs and Jim Rice, scarfing Fenway Franks and watching in glee as the drunken masses in the center-field stands beat the snot out of each other. “Bleacher creatures,” my dad called them.

Greer was no Fenway. But what the place lacked in history and reverence, it made up for in charm and intimacy. At Fenway, you’d consider yourself lucky to get within a hundred yards of a player. At Greer, along the baselines, kids would tug at the jerseys of relievers seated on folding chairs in the dugout. There was no “Green Monster” at Greer — just the rumbling of freight trains behind the outfield wall. I preferred it that way.

My co-workers only added to the delight. I recently told a friend that two types of people worked the stands at Greer — those who, like me, had never had a job, and those who couldn’t get a job anywhere else. It felt a bit like a carnival of outcasts and misfits.

And I felt at home in that crowd. It was a bit like starting over — at Greer I had no classmates, no friends. I could’ve crafted any personality I wanted there, but instead, for once, I felt free to be myself.

I made $4.25 an hour. But there were fringe benefits, and also some company-sponsored perks. You’d get a coupon at the beginning of your shift — good for a free hot dog and a Coke — and you’d also get an inning off to watch the game.

Like many of us, I probably idealize aspects of my childhood in hindsight. I remember young romances and reckless adventures with an intensity they probably never had. But those innings off at Greer, innings spent in the stands as a carefree 14-year-old, were absolutely glorious. I’m sure of it.

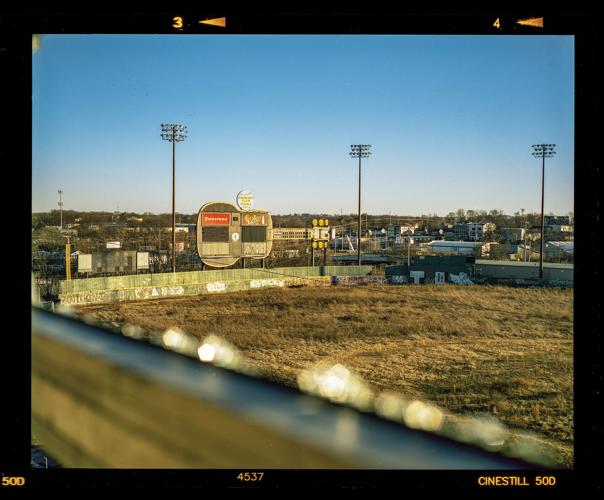

These days, about the only thing most people seem to recall when they think of Greer Stadium is the scoreboard.

The brainchild of Schmittou, the guitar-shaped behemoth rises 80 feet into the air, a 53-foot-tall, 36,000-pound monument to kitsch. Twelve miles of wire, and 8,200 bulbs.

Like so many other wild ideas, the scoreboard began in the humblest of ways.

“I drew it up on a napkin,” Schmittou tells me over the phone.

He’d given Fairtron, the manufacturer, a general idea of what he wanted, and they sent him their response — a guitar standing vertically. That wouldn’t work, Schmittou told them, so he hastily sketched out his idea on a cocktail napkin.

Some months later, the scoreboard showed up — “on about eight 16-wheelers,” Schmittou says with a chuckle. “By the time they installed it [in 1993], it had cost me about a half-a-million dollars.”

In its early days, the scoreboard was a sight to behold. In the ’80s, as an administrator with the Texas Rangers, Schmittou had been to Comiskey Park and had taken a shine to the White Sox’s so-called “exploding scoreboard.” He’d later bring that flare to the minor leagues, making the guitar light up with fireworks after a home run or a Sounds victory.

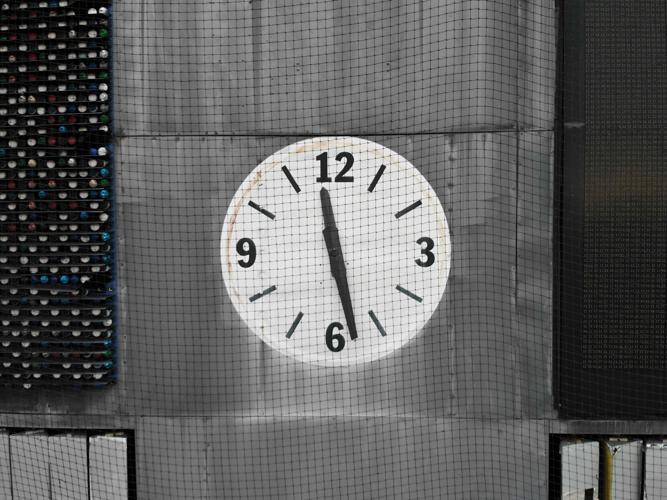

Schmittou sold his stake in the Sounds in 1996, a few years after a failed bid to attract a major-league expansion franchise. In the years between his departure and the stadium’s closure in 2014, the scoreboard, which had become difficult to maintain and find parts for, fell into disrepair. Sometimes after a heavy rain, it barely worked at all.

By the time plans for First Tennessee Park were announced, it was clear the old board was going to be left behind. But even in obsolescence, it was an icon. “When I said the [guitar] wasn’t coming,” Sounds owner Frank Ward told Murfreesboro’s Daily News Journal, “I thought people were going to string me up on the spot.”

Ward’s solution was to construct an entirely new guitar-shaped board at First Tennessee, one with a massive, high-definition screen. It’s impressive — slightly bigger than the old one, in fact — though it feels something like a massive iPad. The old one, with its dim bulbs and dents all over its body and neck thanks to countless home-run balls, has its own bespoke charm.

Unlike nearly everything else at Greer, the scoreboard has a future. Chicago-based AJ Capital saved it from the scrap heap, purchasing it from the city last month for $54,500.

“We’re thrilled to capture such a legendary piece of Nashville’s past and integrate the iconic scoreboard into the forthcoming design of the Nashville Warehouse Company site, just blocks from its original home,” the business said in a statement.

To AJ Capital, the scoreboard’s value is in its nostalgia. It is a chunk of Old Nashville, ready to be plucked from neglect and planted firmly in the present. Part of me feels a little uneasy about a developer cribbing that authenticity. But mostly I feel grateful, happy that a small part of Greer will live on, even as the rest of the park is undergoing demolition.

I ask Schmittou if he’s been back to Greer recently. His grandson, he tells me, is a cameraman and has been filming some of the demolition for a local news outlet. He invited his grandfather down one day to give him one last look at the place.

“I said no, it’s too sad,” Schmittou tells me. “Just let them do what they want with it. I’ve gotten beyond it.”

In my summers at Greer, I never got a foul ball. It drove me crazy then, and for years after.

It’s not that I never had a chance. I’d been in the stands on nights when the stadium was practically empty. A ball would come whizzing toward me, then bounce off the seats, and I’d lock eyes with some eager 7-year-old as he scampered in my direction. Who fights a 7-year old over a souvenir? Not me.

On a recent farewell visit to Greer, I knew where to look. I wriggled through a hole in the chain-link fence behind the outfield wall and into the woods. And there, 25 years later, in the trash and debris, I found my baseball.

But not just one. There were dozens and dozens of home-run balls. Years of rain and neglect had forced most of them out of their jackets — these relics of home-run glory now sad, half-buried blobs of cork and yarn.

To be one of those baseballs, for a moment. The chosen ones that fly toward home plate and into the sweet spot of a perfectly swung bat, sailing through the air, against the skyline, higher and higher — only to plummet into obscurity and ruin. No fans fighting over you, no life spent tucked away in some kid’s baseball glove under his mattress. Just nothing.

That’s how, two-and-a-half decades after I worked my last shift at Greer, I found my baseball, snagged in a shrub well off the ground. And this is no blob of yarn. Its jacket is missing a few stitches, but you can still read the markings: “Rawlings — Official Ball — Pacific Coast League — Made in China.”

Who sent it sailing? I’ll never know. But it nevertheless made its way from China to Nashville, from Nashville onto my desk in Washington, D.C.

Pablo Iglesias Maurer is a writer, photographer and former Hillsboro High School Burro now based in Washington, D.C.