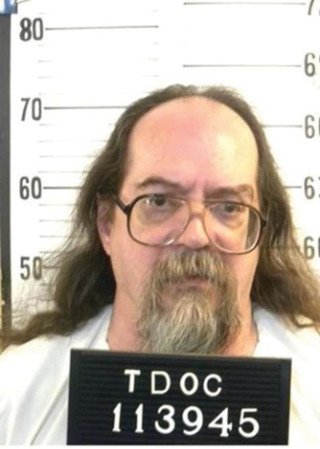

Billy Ray Irick

Alvaro Manrique Barrenechea started making regular visits to Tennessee’s death row around a year-and-a-half ago. Shortly after moving to Nashville from Peru in 2015, he’d started attending Christ Church Cathedral downtown and was quickly drawn to the church’s death row visitation ministry. He’d been a practicing attorney for several years before moving to the States, and he was interested to learn more about the lives of Tennessee’s condemned inmates.

Manrique Barrenechea volunteered and was paired up with a death row prisoner who had expressed an interest in receiving a visitor from the outside. The prisoner he met was a man in his 50s who liked to paint and expressed a childlike enthusiasm for the trading card game Magic: The Gathering. It was Billy Ray Irick, the man Tennessee is set to execute on Thursday, Aug. 9.

A legal and political battle that has swirled with increasing intensity around Irick and his scheduled execution — which would be the first carried out in Tennessee since 2009 — seems to be nearing its end. Irick and more than 30 other prisoners are appealing a Nashville judge’s ruling that upholds Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol, a three-drug cocktail that medical experts say will cause an inmate immense pain. But on Monday night, the Tennessee Supreme Court denied a stay of execution for Irick on the basis that the prisoners’ case is unlikely to succeed. Shortly after that ruling was handed down, Gov. Bill Haslam announced that he will not intervene to stop Irick’s execution, despite pleas from Tennessee's Catholic Bishops and even the European Union's delegation to the United States, which issued "an urgent humanitarian appeal" on Irick's behalf.

“I took an oath to uphold the law,” Haslam said in a written statement released Monday night. “Capital punishment is the law in Tennessee and was ordered in this case by a jury of Tennesseans and upheld by more than a dozen state and federal courts. My role is not to be the 13th juror or the judge or to impose my personal views, but to carefully review the judicial process to make sure it was full and fair. Because of the extremely thorough judicial review of all of the evidence and arguments at every stage in this case, clemency is not appropriate.”

Irick has been on death row since 1986, when he was convicted and sentenced to death for the rape and murder of a 7-year-old Knox County girl named Paula Dyer. Her mother, Kathy Jeffers, recently told WBIR that her name and her story don’t make the news enough. She recounted memories of an outgoing girl who would pick flowers and bring them to new neighbors.

Irick had lived with Paula’s family, the Jeffers, for more than a year, and he would often watch the little girl and her four brothers when her parents had to work. That’s what he’d been asked to do on the night of April 15, 1985. It was around midnight when Irick called the children’s stepfather and told him to come home. “It’s Paula,” he reportedly said, “I can’t wake her up.”

Jeffers says her sons have never forgotten hearing their sister’s screams while they were trapped in a barricaded bedroom.

Irick’s own childhood included questions about his mental health and was punctuated with violent outbursts. He told people that his mother abused him. When he was 13 and living at a facility for abused and emotionally disturbed children, a trip to visit his parents at home was disastrous. According to court documents, the young Irick used an axe to destroy the family’s television set and used a razor to cut up the pajamas that his sister was wearing as she slept.

As the governor noted in his statement Monday night, Irick was examined by a mental health expert after his arrest and ruled competent to stand trial. But that expert, Dr. Clifton Tennison, said he no longer had confidence in that assessment after reviewing affidavits signed by members of the Jeffers family in 1999 that raised doubts about Irick’s mental state at the time of the crime. The family said Irick had been “hearing voices” and “taking instructions from the devil,” and an investigator learned that a machete-wielding Irick had chased a young girl down a Knoxville street in broad daylight just days or weeks before Paula Dyer’s murder.

But Manrique Barrenechea, who is 29 years old, isn’t very familiar with all those details. In fact, he says, he made a decision when he started visiting Irick not to dig into his case and his past. When people learn about his relationship with Irick, he says, they often ask what Irick did. Manrique Barrenechea doesn’t know the man who did those things, though.

“I don’t know much more of Billy in his past, but I know about Billy for the last year-and-a-half,” he tells the Scene, less than an hour before news breaks about the Supreme Court’s ruling. “That’s the picture and image I have of Billy.”

For that reason, reading the news in recent months has been a strange experience for him.

“I recently happened to be scrolling through some of the news and I saw a mugshot of Billy, and it just looks so different from the person that I know,” he says. “It’s completely different from the person that I’ve known for the past year-and-a-half.”

The Billy Ray Irick that Manrique Barrenechea knows can be funny, cracking jokes at their Monday evening visits. He likes football, but not soccer. He loves to paint. And he loves Magic: The Gathering.

Manrique Barrenechea knew of Magic but had never played when Irick started talking to him about it at their visits and in letters. So he bought a deck and learned how to play online, if only so that he could relate more to the death row prisoner he was getting to know. At one point, he says, Irick told him that he and other prisoners he played with had trouble on occasion because they didn’t have a rule book. So Manrique Barrenechea got one and jumped through the necessary hoops to send it to Irick in the prison.

“He was telling me how some of the things that they weren’t very sure about in the game, they were explained in the rule book,” Manrique Barrenechea says. “So they spent some time going over the rules and making sure they were playing the way it was supposed to be played.”

At one of their first visits, Irick told Manrique Barrenechea he wanted to paint something for his new visitor and asked if he had any requests. Manrique Barrenechea says he asked Irick to name a place from a fond memory and Irick told him that he’d loved his time working on a shrimp boat in Louisiana. He painted it and Manrique Barrenechea has it in his home now.

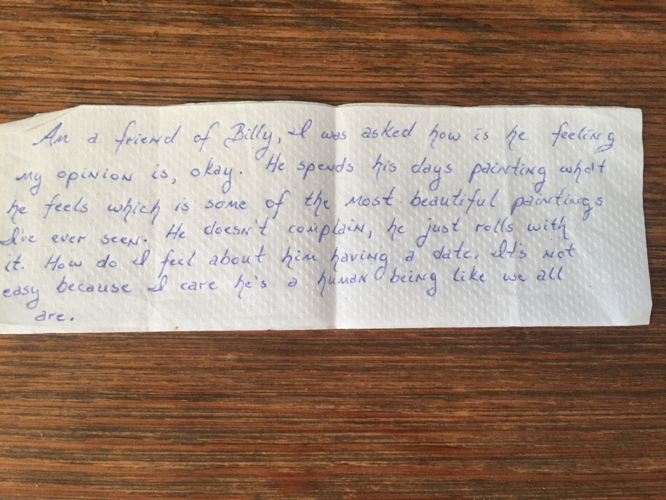

Irick is said to paint every day. In a note scrawled on a napkin and passed to the Scene through a different death row visitor, one of Irick’s fellow death row prisoners says he’s quite good at it.

“He spends his days painting what he feels which is some of the most beautiful paintings I’ve ever seen,” the man writes. “He doesn’t complain, he just rolls with it. How do I feel about him having a date[?] It’s not easy because I care he’s a human being like we all are.”

Sources who visited death row — Unit 2 at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville — on Monday night say Irick was there for visiting hours, present if a little subdued. He had not yet been moved to death watch. The state’s protocol states that a prisoner will be moved to death watch (a holding cell near the execution chamber) approximately 72 hours before their scheduled execution.

One death row prisoner, according to someone who visited the prison Monday night, says the inmates have watched through their small windows as staging areas are set up outside the prison in preparation for Irick’s execution Thursday night. In a poem passed to a visitor, one of the prisoners describes the feeling of sitting on death row as an execution date approaches.

“I sat pondering, what was, how I woke up with four walls around me, family dying.

Three with dates, eight at stake. Fighting to stay alive, yet knowing I too, share the same fate.”

The attorneys representing Irick will now seek a stay in the federal court system, a process that will likely lead them to the United States Supreme Court. Irick has been scheduled to die before — three times in the past four years — but he’s never been this close.

Once on death watch, Irick will be asked what he wants for his last meal. He may be allowed a final visit with immediate family during which physical contact is allowed. He will be observed around the clock, lest he try to end his own life before the state can do it at the appointed time — Thursday, Aug. 9, at 7 p.m.

Manrique Barrenechea wasn’t able to go to the prison Monday night, but he was there a week ago for what will likely be his last visit with the man he knows simply as Billy.

“It’s definitely going to be something that I’ll keep with me,” he says. “I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I’m grateful that I was able to get to know this man.”