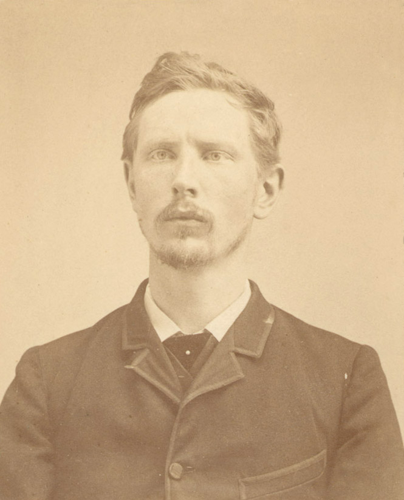

Famed anarchist and onetime Nashvillian Adolph Fischer

In his list of firsts vis a vis the Aug. 1 elections over at sister pub the NashvillePost, Stephen Elliott noted something interesting about District 5's councilmember-elect.

Parker, who ran as a contrast to term-limited incumbent Scott Davis, is likely the first Democratic Socialist on the Metro Council.

Though once described by Belle Meade resident Herb Shayne as "a hotbed of social rest," Nashville has harbored its fair share of radicals of both the anarchist and socialist varieties in the past 150 years or so. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the fairly robust Italian and German immigrant communities served as the nexus of leftism, though they eventually attracted WASPier comrades.

In fact, Adolph Fischer — one of the Haymarket Martyrs hanged on the rather dubious conviction of throwing a bomb at the May 4, 1886, protest in Chicago (the Wobblies, unsurprisingly, have a good write-up of the whole thing, though it's admittedly biased) — lived in Nashville for a time before going north. Here he worked as a "compositor" for the Anzeiger des Südens, a German-language paper (its name translates to "Indicator of the South," which is pretty great) owned by his brother William. William Fischer told The Tennessean his brother left town in 1884 because he wasn't allowed to "advocate socialistic ideas" in the Anzeiger. William also — repeatedly — emphasized that he didn't share his brother's radical beliefs, but that Adolph thought he was doing the right thing.

By the early 20th century, the (by then capital-lettered) Socialists were numerous enough to host out-of-town speakers at the Twin Hall on what was then Cedar Street (the hall was roughly where the John Sevier State Office Building is today). Seth McCallen, editor of the popular socialist magazine The National Ripsaw, even relocated from St. Louis to Nashville, editing the publication until he had a stroke at his Hillsboro Pike home in 1909.

Also in 1909, Nashville's Socialists named a full slate of nominees for October's city elections. It's worth noting here that the city's Republicans, then so numerous as to be able to meet in a bank president's office, declined to sponsor candidates. According to The Tennessean, though John Ray was the Socialist nominee for mayor, the "leading light" for socialist thought in the city was Dr. W.H. Jackson, a "psychic" and "magnetic healer" who was nominated for the board of public works.

The Socialists did not win a single election against the massive Democratic Party machine (The Tennessean, otherwise fair and occasionally kind to the leftists, noted Socialism was not a "viable party" in Nashville), but nevertheless made history. Annie Murphy, a seamstress who lived at what is now the site of the Niido apartments on Fifth Avenue South, ran for City Council. Murphy is believed to be the first woman to seek city office in Nashville, doing so a full 11 years before women won the right to vote.

The lifelong socialist, who told The Tennessean she learned the tenets of the movement on her mother's knee in New Orleans, espoused principles that, uh, don't seem particularly socialist now: "The city which is governed best is governed least," for example.

But she also had a pretty hardy bit of girl power:

"You know all of the great reformations of the world's history have been led by a woman, and if not this time, I hope the day is not far distant when a woman will not only be elevated to the mayor's chair in the city of Nashville, but the majority of the council will be female. ... I have just as much legal right to run for office as any man in this city, and if elected they cannot prevent me from taking my seat."

The Socialists did run into some trouble. They frequently held "public speakings" downtown, and a handful of them were arrested in September when they relocated to the public square, charged with blocking the road. The charges were dismissed, the judge saying they had just as much right to have outdoor speakings as anybody else. The Tennessean defended their rights as well. Emboldened, by November, they'd rescheduled the events to Sunday afternoons and relocated down to the wharf by the river. The problem here is that this was a popular place for preachers to pontificate, and a dispute arose after the Socialists passed the hat one Sunday to pay for pamphlets. One of the preachers said some of the folks in attendance intended to give instead to the preachers, and thus the churches were entitled to half the proceeds. The Socialists refused, prompting a petition that was apparently enough cause to get the reds banned from the riverside. Run off from the banks by the Nashville police, the Socialists instead spoke from the deck of a flatboat. Given that the Cumberland then, as now, is free for navigation, they were "left unmolested" by the police force.

World War I and subsequent decades of red scares dimmed the red light in Nashville as it did in many places. Perhaps the most prominent post-World War II Communist in the city was Dr. Lee Lorch, who was head of the mathematics department at Fisk. Notably, Lorch, who was white, tried to integrate Nashville's schools after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 by asking the city's school board to admit his daughter to all-black Pearl Elementary. His request was denied. Eventually, Lorch — who had a difficult relationship with many of the city's black civil rights leaders, including Z. Alexander Looby — was called to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee about his Communist affiliation. He refused to say whether he'd continued his activities after taking the Fisk job, and was held in contempt of Congress and dismissed by Fisk in 1955.