The one thing I hope we never take for granted about Nashville history is that, regardless of how much change comes to the city, we can still go see where things happened. Thanks to the Tennessee State Library and Archives (Unofficial Motto: Please Stop Giving Us Unofficial Mottos, Betsy), the Nashville archives, the State Museum, and many other awesome resources, you can put your hands on a bunch of information about historical figures and then you can drive to where they lived and see it for yourself.

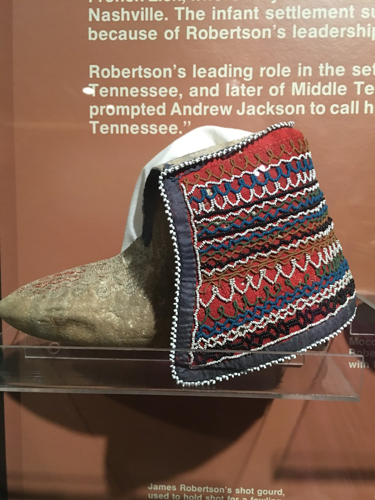

This weekend, for instance, I was determined to learn more about the early history of The Nations. I was able to go to the Tennessee State Museum to see the very shoes James Robertson wore while meeting with the Chickasaw Nation in the shade of the Treaty Oak, and then I was able to go to the place where the Treaty Oak stood and stand myself where James Robertson stood in those shoes.

Sometimes, when you’re so fortunate to have the kinds of resources we have, you take for granted that it just must be this easy every place. No, Nashville. We are very, very lucky.

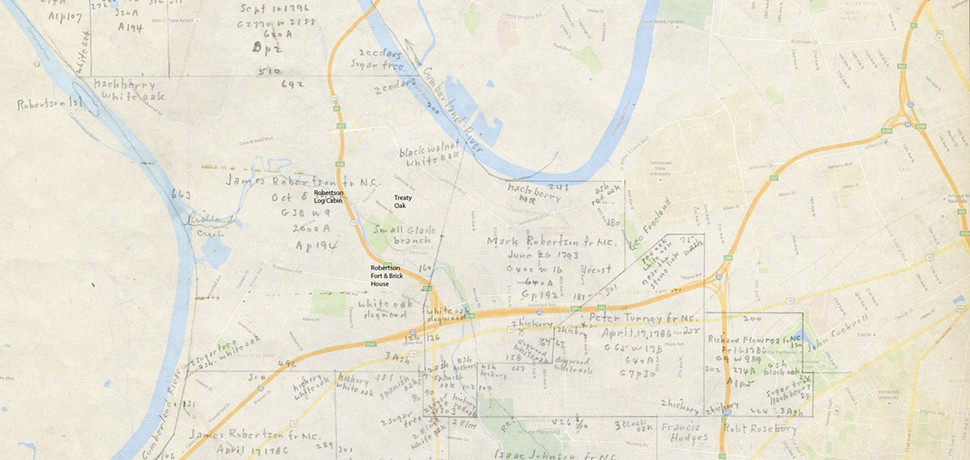

OK, so the history of The Nations is tied closely to the Robertson family. James Robertson and his wife Charlotte, of Charlotte Pike fame, are probably the two most well-known Robertsons currently, but a bunch of James’ siblings came to the Nashville area. The history of The Nations concerns the families of three of them — James and Charlotte, James’ younger brother Mark and, tangentially, James’ sister Ann.

(Ann deserves a yearly parade and a passel of punk rock cheerleaders standing in Centennial Park shouting “Hell yes, Ann!” while shaking their pompoms until all passers-by go into a frenzy from curiosity about her. But for the sake of this discussion, what you need to know is that Ann was such a bad-ass that she got her own land grant at a time when women didn’t own property and that her first husband was named David Johnson or Johnston and her second husband was John Cockrill, of the Cockrill Bend under discussion.)

James Robertson and his party walked to what would become Nashville, arriving on Christmas Day, 1779. Mark was with him. They lived in the fort we now refer to as Fort Nashboro, but which they probably just called The Fort or the French Lick Fort, long enough for James’ son, Felix, to be born and for the family to live through the Battle of the Bluffs on April 2, 1781. Land grants were handed out after this, and the Robertsons we’re concerned with moved out to the general area of The Nations.

James and Charlotte first moved into a log cabin, probably in 1782 or 1783 (the replica of which you can see if you look out your window at just the right time by Nashville West) on the banks of Richland Creek. In November 1783, Piominko (the Twitter account of the Chickasaw Nation sent me this article about the correct spelling of his name, for the curious) and other Chickasaw leaders met with Nashville’s leaders to negotiate a peace treaty. This meeting is believed to have happened there at the Treaty Oak in The Nations. The awesome shoes Chickasaw bead-workers made for James were given to him on this occasion.

After this, the Robertsons built themselves a station (remember, in general, a station is a privately owned fort) and then a brick house in that station on the creek, a little farther upstream from the Cumberland.

The Nashville City Cemetery Association has a story from the Sept. 27, 1902, Nashville Daily News about the destruction of that brick house. We are, of course, interested in its creation:

The brick for the building was burned on the place, and were larger and heavier than those in present use. The Indians, presumably, aided in the work of brickmaking, as their hieroglyphics and signs are found impressed in several instances on the flat side of the brick. Some of these have been presented to the State Historical Society, and an effort will be made to decipher the meaning of the symbol. With what intent the savage left his mark upon such material it would be interesting to know.

The author of the article believes the brick house was built before the death of Peyton Robertson (more on this tomorrow), which she dates to 1788. Peyton was killed in 1787, but either date makes the existence of the brick home quite remarkable.

We talked before about what you need to build a brick house in Middle Tennessee before 1792 — a workforce, a secure shelter for your workforce, a kiln, and someone who could run it. I was intrigued by this idea that the bricks from the house may have had some kind of marking on them. I tracked down at least one brick to the State Museum and asked Jeff Sellers, who works there, if he could find it. He was able to find the record that indicated the State Museum had received the brick, but it had been lost over the years. I asked Aaron Deter-Wolf, at the State Archaeologist’s office, if they had any bricks from the Robertson House and what they made of this idea that Indians helped make bricks.

He agreed with me that it’s very unlikely that Indians would have made bricks for the Robertsons, because, as friendly as the Robertsons were with Piominko and the Chickasaw Nation, that’s a lot of hard work to do for one’s friends. But there are enough stories of the Chickasaw coming to observe the house being built that Deter-Wolf thinks that could be true. That makes sense to me. It’s good technology to have — a building material that’s impossible to light on fire and makes a good defense from your enemies. The Chickasaw at the time could have been very interested in a building material Creek weaponry couldn’t penetrate, for instance.

But the Chickasaw would have faced the exact same problem that almost everyone else — except for the Robertsons — faced at the time. Where the hell do you find a guy who can build a fire to a specific temperature and hold it at that temperature for days?

Why didn’t the Robertsons face this same problem? What if I told you that James and Charlotte’s daughter, also named Charlotte, married a Napier? No? OK, here’s my theory: As soon as the Robertsons decided they were going to get into the iron-producing business, it became worthwhile for them to spend the money on a skilled enslaved man who could build a fire to a specific temperature and hold it at that temperature for days. Once he was done making bricks, they could move him out to the furnaces.

If Nashville had had a white brickmaker at the time, believe me, we’d remember his name. People's houses and forts were being burned down by pissed off Native Americans left and right. A white brickmaker would have been the biggest goddamn hero of the era. Every person who could have afforded it would have been living in a brick house. Instead, we have a very few brick houses from this era (again, speaking of before 1795) and a silence where the explanation for where the brick came from should be (with the Bowen-Campbell House in Goodlettsville being the exception, since they say those bricks came from Louisville). That’s a sure sign of the work of an enslaved tradesman or a very few enslaved tradesmen. I’m estimating that in all of Middle Tennessee before 1792, we’re talking about fewer than five men with the necessary skills — whomever the Robertsons had, whomever the northside Ewings had, possibly someone up near what would become Gallatin, and possibly someone near Franklin.

The fact that the Robertsons were living in a brick house in this era tells you that they were really rich — not because they could afford a brick house, but because they could afford the enslaved skilled man to run the kiln.