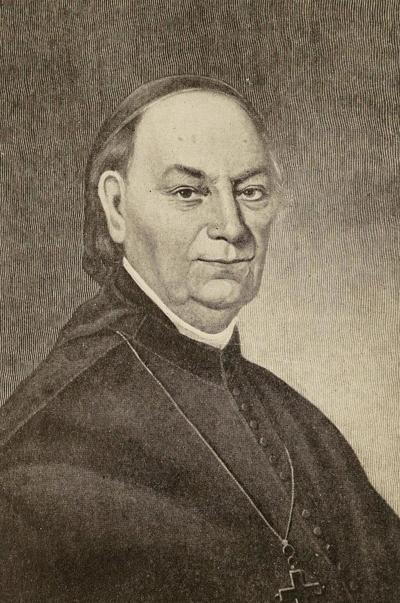

The Rev. Richard Pius Miles, Nashville's first bishop

As you all know, one of my ongoing history obsessions is trying to understand what this place was like right before and as it was becoming Nashville. And the sense I have is that we don’t really have a clear picture. Well, scholars might. But I don’t. And I can’t always find resources to tell me.

One scab that I regularly pick at is this: If this area wasn’t the unpeopled pristine landscape we’ve been told it was, who actually was here? And to this end, we know that Timothy Demonbreun was here, fur trading out of the old Shawnee fort that sat on the mound that used to be just south of where the Jefferson Street bridge is now. We also know that old Shawnee fort was probably the fort Martin Chartier and his family lived in back in the 1690s. Our early history is linked to the early history of Catholicism in the state.

Great! Let’s find out about early Catholicism. We know Demonbreun and his many children were here. Joseph Durratt/Deroque was here, because Demonbreun foisted his second wife off onto him when his first wife reappeared. Demonbreun had a relative named Fagot who got in a fight with Andrew Jackson. The Rogans up in Sumner County were Catholic and one of the sons went to Missouri to work with the Spanish government, and that’s who I can think of just off the top of my head.

But even though there were prominent Catholic families here in Middle Tennessee at our city’s founding, resources about who they were and what they were up to are scarce. The 1887 History of Tennessee From the Earliest Time to the Present has some interesting tidbits. The first mass held in Nashville was on May 10, 1821. The priests who presided over it stayed with Demonbreun. The number of Catholics in the state was about 100. (If that's accurate, it means I just named 5 percent of Catholics in the state at the time off the top of my head, which is wild.) Then the first Catholic church was erected on the north side of where the Capitol is now in 1830. But there’s also this: “Previous to this time but four missionary visits had been made to the State since the early French settlements, and the number of Catholics in the State did not much exceed 100.”

So, hold on. In the 1820s, there were 100 or so Catholics in the state. Fine. Cool. Makes sense. And before that, four missionary visits had been made. OK, makes sense. Someone had to come down and baptize all the children Timothy Demonbreun was fathering. But what is this “since the early French settlements” business? What early French settlements? Martin Chartier burned down Peoria (no one who has ever smelled Peoria blames him for this), which was an act of treason against France, since he was in the French military and Peoria at the time was a French fort known as Crevecoeur. Then he joined the Shawnee, married a Shawnee woman, and seems to have been entrenched enough in her culture that their kids all got Shawnee names. I find it unlikely that the Catholic church would have sent him a missionary — though from their perspective he certainly needed one.

Have you ever heard that there were French settlements in Tennessee? Fur traders, yes, obviously. Short-lived forts? A couple over on the Mississippi. But settlements? This is peculiar and I’d like to learn more.

Also, allegedly, Tennessee’s early Catholics kind of sucked. In John Gilmary Shea’s 1890 book History of the Catholic Church in the United States, he recounts that — when Bishop Richard Pius Miles was consecrated on Sept. 16, 1838, in preparation for him being made the first Bishop of Nashville — during the sermon the Rev. John Timon preached about how much going to Nashville was going to suck for Miles. Shea then says that Bishop Miles arrived here on Oct. 18, 1838, after the Rev. Durbin had time to fix the “wretched” little church they were making Miles’ cathedral. Shea then sends the Rev. Miles on his way to “explore his diocese, learn where Catholics were, and what prospect there might be of building up churches.”

But let’s flip over to Richard Henry Clarke’s Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States, published in 1872, where the situation is described in more detail. More terrible, hilarious detail:

Bishop Miles proceeded at once to Nashville and took possession of his see. No new diocese ever erected in this country, probably, was so destitute as that of Tennessee when its first Bishop entered it. He stood alone in that large diocese, without support, sympathy, or means. […] One or two miserable sheds, in a dilapidated and falling condition, were the only places in the State in which the faithful could assemble to attend divine service. The bishop, having no residence, was compelled to take board at Nashville, and commence the work of organizing, or rather erecting the Church of Tennessee. At this disheartening crisis the Bishop was taken ill with the prevailing fever of the climate, so fatal to the unacclimated.

Y’all, Bishop Miles got here, saw his falling-down shed of a church, where I guess he was also supposed to sleep? And that dude’s first reaction was to get sick and try to die. Frederick Stump’s wooden house has stood since the 1790s. The wooden buildings out back of Sunnyside down in Sevier Park have been standing since before the Civil War. Nashville might suck at public transportation and road repair and standing up to developers, but we know how to build shit that lasts. If you want to get rid of a historic building in Nashville, you need to either knock it down or wait for someone to blow it up. How was a building erected in 1830 this dilapidated by 1838?

Bishop Miles did not die. A priest just happened to be wandering the countryside, and when he popped into Nashville to let the bishop know he was in the area, he saw how sick the bishop was and nursed him back to health. Then the bishop went around and got more priests and got some churches together. The rest of his life is accounted for.

But it’s still not clear to me why being the Bishop of Nashville was supposed to suck so much. Was it just that Catholics in Nashville were terrible carpenters? Was it all the traveling? And where were these French settlements? Were they maybe haunted? Because otherwise, all the stories seem to boil down to: “We wish we had a church and a priest to go in it, but alas ...” And then Bishop Miles shows up, buoys their spirits, and they build a church and eventually get a priest. No gun battles, no Da Vinci Code-esque elaborate plots, not even a good ancient curse to keep things lively.

It's a mystery. And not one I’m sure how to solve. But if Nashville’s early Catholics were so terrible, I’m dying to know why.