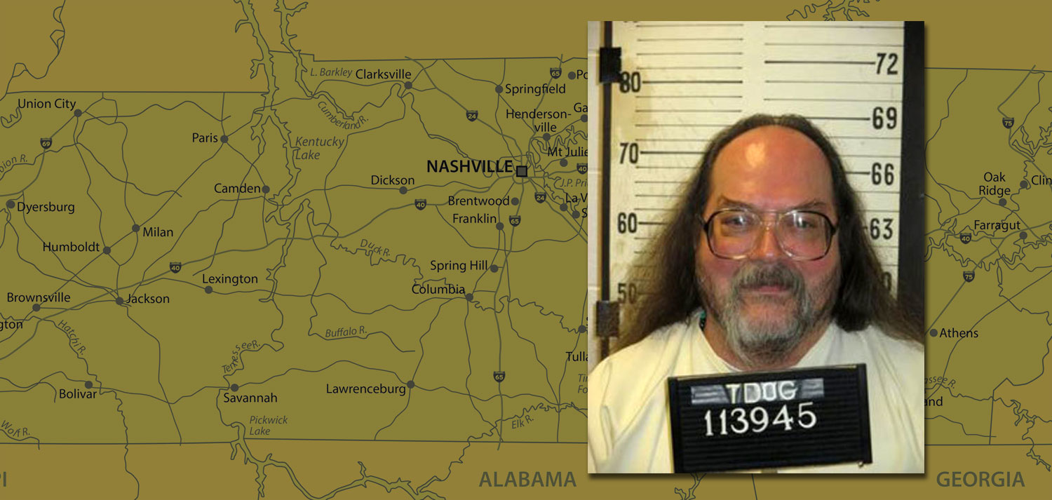

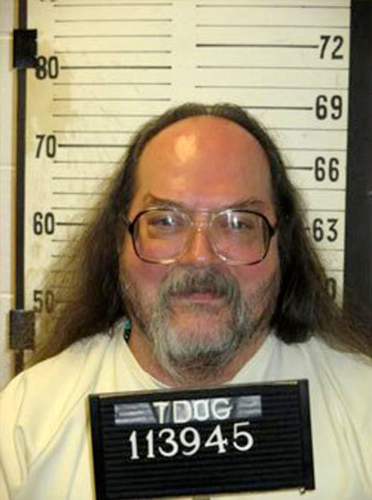

Billy Ray Irick

Billy Ray Irick was lying on a gurney, eyes closed and snoring loudly at 7:34 p.m. on Aug. 9 when Tony Mays shouted his name.

“Billy!” yelled Mays, the warden at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution, which houses Tennessee’s death row.

“Billy!” he shouted again, his voice carried into witness rooms through a microphone hanging in the center of the brightly lit execution chamber.

Irick, a heavy man with shoulder-length hair and an unkempt beard wearing an off-white Tennessee Department of Correction jumpsuit, did not appear to respond in any way. His hands were taped down, and there were heavy straps across his chest, arms and legs; his belly protruded from between the straps, visibly contracting with each breath.

He had already said his last words, a seemingly spontaneous apology. He had already been injected with midazolam, a sedative that is the first chemical in Tennessee’s three-drug lethal injection cocktail. Once midazolam has had time to take effect, Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol calls for a consciousness check before the next two drugs are administered.

I don’t know what Billy Ray Irick thought this night would be like. I don’t know what I thought it would be like. But it was here now, 32 years after Irick was sent to death row. This was his execution. Tennessee was putting him to death for the 1985 rape and murder of Paula Dyer, a 7-year-old girl he had been entrusted to babysit. The Tennessee Supreme Court, Gov. Bill Haslam and the Supreme Court of the United States had all declined to intervene. By 7:48 p.m. Billy Ray Irick would be dead, just shy of his 60th birthday.

Every part of this story is suitable for a nightmare, but the sound that will not stop echoing in my mind is that of Mays shouting, “Billy! Billy!” Perhaps it’s because the use of Irick’s first name stood in such stark contrast to the inhuman and impersonal quality of almost everything else about the process. It was also a reminder that Mays and the people who staff death row personally knew the man they were tasked with killing on this night, and they knew him as Billy.

But even more haunting is the knowledge that, according to leading anesthesiologists and medical experts, the results of a consciousness check are almost meaningless. Midazolam, they say, cannot spare a person from the effect of the next two drugs. For that reason, they considered it almost a certainty that Irick would feel what happened next, that it would be excruciating, and that, because the second drug is a paralytic, he would be largely unable to show it.

Lethal injection is commonly described as an execution dressed up like a medical procedure. That’s true in a way. But for those serving as media witnesses, the process is both more mundane and more disturbing than that. It is a disorienting and unsettling mashup of bureaucracy and barbarism. Imagine going to the airport, winding through various levels of security, removing shoes and belts, passing through a metal detector, pat-downs and body scanners, and at the end of the process, being invited into a lair where public officials perform a human experiment that ends in death. At one point Thursday night, as we waited to be led to the execution chamber, Irick’s attorney Gene Shiles remarked that the whole process was “Kafkaesque.” If that sounds cliché, don’t blame him. It’s true.

Around 5:30 p.m., the media witnesses — chosen through a TDOC lottery — were led into the prison. The entryway smelled of fresh paint. Framed placards bearing the department’s “guiding principles” and pronouncements about the exciting opportunities available to correctional staff hung on the walls. We were led into a conference room with light-blue cinder-block walls where we joined Shiles, Deputy Attorney General Scott Sutherland, Knox County Sheriff Jimmy “J.J.” Jones and TDOC communications director Neysa Taylor. There the staff — whose calm kindness was appreciated, but added to the unsettling nature of the evening — offered us notepads and pencils, bottled water and government coffee. No one in the room had seen an execution before.

Jones and Sutherland declined to comment about Irick’s case or the looming execution, but Shiles, who represented Irick for almost 20 years, seemed eager to talk. After all, what else was there to do? An affable man with a gentle demeanor and a warm Southern accent, he bluntly acknowledged the heinous crime Irick committed more than 30 years ago. But he also reflected mournfully on Irick’s life — nearly 60 years of darkness.

“I don’t know if there’s been one day in his whole life when his life was celebrated,” Shiles said. “Even the day he was born, I don’t think was a happy day.”

In the end, Irick spent more of his life on death row than he did on the outside.

Irick was just 6 years old when he was first referred to a mental health facility. As a young boy he told people outside his home that his mother would tie him up with a rope and beat him. There were long stretches during which he rarely saw his parents, whose mental and emotional stability was also in question. During a visit home from another institution when he was 13, Irick destroyed his family’s television set with an ax. Around 15 years later, in the weeks before he raped and strangled 7-year-old Paula Dyer, Irick chased a school-age girl down a Knoxville street while wielding a machete. Years later, Dyer’s family, the Jeffers — with whom Irick lived for a time — told an investigator that Irick was “taking instructions from the devil” and that he’d said, “The only person who tells me what to do is the voice.” On one evening, according to a family member, Irick had been frantic that the police were going to enter the home and kill them with chainsaws.

In the conference room, clutching a folder stuffed with papers, Shiles said he didn’t believe the execution would really happen until the Supreme Court of the United States denied Irick’s request for a stay on Thursday afternoon.

“I thought someone would look at the facts,” he said, referring to Irick’s mental health history. Numerous state and national mental health advocacy organizations had urged the governor to halt the execution on those grounds.

After some amount of time — I can only guess how much, as we were not allowed to keep our phones or wear a watch once inside the facility — we were led outside, down a sidewalk, through two large chain-link gates topped with barbed wire to another conference room. More bottled water. More nervous small talk. The sound of heavy prison doors shutting somewhere outside the room, the echo of walkie-talkie conversations. Then a guard tasked with leading us from checkpoint to checkpoint looked up from her position at the door. “You guys ready?”

The question was rhetorical.

A grim feature of the layout at Riverbend is that the execution chamber sits just to the side of a large visitation gallery. As we were led toward the chamber, we walked in between the chairs where prisoners can sit and talk to visitors during weekly visitation hours. Death row prisoners and their visitors meet in a separate room. That's where, just days ago, Billy Ray Irick mingled among a crowd that was, according to visitors, palpably tense.

We arrived at the viewing room that looks into the execution chamber — a small, square room with 16 theater-style chairs — at 6:43 p.m. A guard took a position at the door, and the lights were shut out. We sat in the dark, watching a small digital clock on a phone that hung on the wall, for more than 40 minutes. During that period, two men quietly joined us in the room; one of them was a prison chaplain who had met with Irick leading up to his execution.

At around 7:12 p.m., Sutherland — the deputy attorney general — and Shiles were called out of the room to observe the IVs being placed in Irick’s arms. There had been some confusion over when they were supposed to be taken to the execution chamber. From the viewing room, we could hear what sounded like gurney wheels squeaking and rattling on the other side of the door. When Sutherland and Shiles returned around 7:25 p.m., Shiles told reporters he’d kissed Irick on the forehead and touched his arm.

Around a minute later, the blinds were opened and there was Irick, strapped to the gurney, his eyes open. Mays and a deputy stood a foot or two from the gurney in black suits, their hands folded in front of them.

“Billy, do you have any last words?” Mays asked Irick.

Irick sighed and said, “No.”

Mays wiped his hand over his own face, signaling the executioners — who were not visible to witnesses — to start administering the drugs. But it was at that point Irick blurted out his final statement.

“I just wanna say I’m really sorry, and that — that’s it.”

I had offered Irick a chance to give a written statement 24 hours before, through an attorney, but he declined.

Soon Irick’s eyes closed, and he began to snore. Around seven minutes later came the consciousness check.

“Billy!”

“Billy!”

According to the theory of this constantly litigated process, this check is in place for prison officials to make sure that the condemned inmate is unconscious and supposedly spared the torture that would otherwise come next. But around two minutes later, Irick did appear to react physically to the second drug.

He jolted and produced what sounded like a cough or a choking noise. He moved his head slightly and appeared to briefly strain his forearms against the restraints. In a statement following the execution, Federal Public Defender Kelley Henry said those were signs of the kind of trouble warned about in a lawsuit filed by more than 30 death row prisoners, including Irick.

“This means that the second and third drugs were administered even though Mr. Irick was not unconscious,” she wrote. “The descriptions also raise troubling questions about the State’s attempt to mask the signs of consciousness including by taping down his hands which would have prevented the witnesses from observing the failure of the midazolam.”

Around 7:37 p.m., the color in Irick’s face changed to almost purple. After that, we watched for nearly 10 minutes as he lay there. He did not appear to be breathing any longer.

Paula Dyer’s family was present for the execution, seated in a different room. While our group of witnesses was positioned to Irick’s right, the victim’s family was seated behind a glass window directly in front of him. From her vantage point in our viewing room, Knoxville News Sentinel reporter Jamie Satterfield said she could see one family member lean forward and bite a fingernail during the consciousness check, while another slumped back into their chair after Irick appeared to take his final breath.

Irick did not appear to have any family in attendance.

Mays shut the blinds at 7:46 p.m. and, several minutes later, spoke over a PA.

“That concludes the execution of Billy Ray Irick. Time of death 7:48 p.m. Please exit now.”

We were led back through the maze of hallways and security checkpoints and out into the night. A bevy of other reporters waited in the parking lot for us to brief them on a night spent in the darkest corner of Tennessee’s criminal justice system.

Paula Dyer would have turned 40 this year. Perhaps she would have children of her own. Her mother spoke recently about how she would pick flowers and bring them to new neighbors. She was robbed of everything she might have been, and there’s no disputing that her death was cruel and unusual. Her brothers were victims too; they were locked in a nearby bedroom and could hear their sister scream as she was brutalized.

As a result, there will no doubt be many Tennesseans who feel Billy Ray Irick got what he deserved Thursday night. To some, the debate, discussion and litigation over how the state kills men like him seems absurd. In a way, they’re not wrong. Surely the means by which the state puts its own citizens to death is a secondary question to whether the state should be doing it at all.

Be that as it may, I saw Tennessee’s death penalty in practice last night, and watched as state officials killed a man in my name and in yours. They strapped him to a gurney and injected him with drugs we have every reason to believe cause unimaginable pain. There appeared to be signs that he did feel something, but only briefly. Once the second drug, a paralytic, took effect, he was unable to move regardless.

Did the state of Tennessee torture a man to death Thursday night? I was in the room, and I suppose I couldn’t say for sure.

Note: An earlier version of this story misstated which visitors gallery is used by death row prisoners. On this night, media witnesses walked through the visitors gallery used by prisoners from the general population. Death row prisoners use a separate room to meet with their visitors.