C.W. Nance's 1845 hand-drawn map showing the reroute of White's Creek Turnpike across the Cumberland River from Nashville

By now, Pith readers know how much I love the fact that Nashville’s pikes go to the places they’re named for. But one pike has remained unsatisfying to me: Dickerson Pike, originally the Dickinson Meeting House Road. Where was this meeting house that the road went to?

No one seems to know. So I thought I would try to find it.

Fortunately, the name of the property owner where the meeting house sat is right in the name of the road — Dickinson. And this 1845 map at the Tennessee State Library and Archives shows that the road had that name in ... um, yes, 1845. So, we’re looking for Dickinsons who lived out in that direction before 1845.

OK, cool. No problem.

Well, a couple of problems. First, I can’t find a map at my beloved TSLA that shows any Dickinsons out that way. Second, sometimes you can guess where someone was located based on in-laws — maybe you can’t find any Dickinsons, but you find the names of dudes their daughters married. But there were at least three Dickinson families in Nashville, and they married everybody.

Stick with me here. This gets confusing. First, and most easily dismissed, is the family of Charles Dickinson. Charles, Tennessee history buffs may recall, was killed by Andrew Jackson in a duel in Kentucky. His family came out of Maryland and lived over near what is now West End Middle School.

Then there’s the family of Jacob McGavock Dickinson. This Dickinson was the secretary of war under President Taft. He owned Travellers Rest, Belle Meade and Polk Place. He is, indeed, the person who had the Polks disinterred so he could tear down their house and put up an apartment building. He also had a respectable mustache. Jacob’s great-grandfather was Felix Grundy, associate of Andrew Jackson, and his grandfather was Jacob McGavock, who was Andrew Jackson’s military aide.

Jacob’s grandfather, William Dickinson, was born in Virginia in 1779. William’s father was Archelaus Dickinson, which is a name that stands out when you see it. So if they are related to any of the other Dickinson families, it ought to be easy enough to tell, since there isn't going to be an army of Archelaus Dickinsons out there.

So these Dickinsons are friends with Andrew Jackson and married into some of Nashville’s most prominent families — Grundys, McGavocks, Overtons, Hardings, etc. — and they come out of Virginia.

But wait! There’s another Dickinson family. And the patriarch of this family is also named Jacob Dickinson, except they come out of North Carolina. This Jacob Dickinson, who died in Davidson County in 1816, had a bunch of kids — Mary Polly, Charity, Jacob Jr., William Thomas (sometimes just called Thomas), Sarah, Jane, Isaac and Milbury (a girl). We’re going to need Milbury in a second, so keep her in mind. Charity was married to William Donelson, Rachel Donelson Robards Jackson’s brother! These Dickinsons are Jackson’s in-laws! As far as I can tell, there are three Dickinson families — the family of Andrew Jackson’s mortal enemy, the family of Andrew Jackson’s friends, and the family of Andrew Jackson’s family.

The Jacob Dickinson of this third family left a will. (As a side note, in this will he reveals that he and his second wife had a prenuptial agreement that her assets from her first husband would go to the children of that marriage, which means that Adelicia Acklen’s situation might not have been all that unusual.) I won’t go into the whole thing here, but it’s basically: “Give my grain to these people. Destroy the families of the people I keep enslaved in these ways. Here’s the property I want to give my sons.” We are concerned with that last bit:

I give and leave to my son William Thomas Dickinson the plantation and the part of the tract of land whereon I now live bounded as follows: Beginning at an Ironwood [seems like there’s possibly an "on" missing here] Joseph Philips corner thence running due East to the public road, thence northwardly along said road to Jacob Dickinson junior’s formerly [illegible, possibly “shared”?] line thence with said line East to a sugar tree and walnut thence South one hundred and sixty four poles to a sugar tree on Philips [illegible] preemption line then with said line west one hundred and thirty four poles to a hickory and sugar tree thence South one hundred and thirty one poles to William Moore’s north East corner a sugar tree then west one hundred and seventy poles to a sugar tree on Joseph Philips East boundary thence with his line north to the beginning corner.

OK, so here’s what we can discern from this, I think. Wherever this Jacob Dickinson lived, Joseph Philips was his southern neighbor. Can we find Joseph on a map? Sadly, no. But we can find him in a graveyard. Joseph Philips is buried in the old Sylvan Hall graveyard — Sylvan Hall being the name of the Philips house that came into the possession of William D. Philips, Joseph’s son.

And now that we’ve found Joseph, we learn that his wife’s name was Milbiry. In fact, William also named his daughter Milbiry. Clearly, Milbury Dickinson was named after them. But get this! Milbiry Philips grew up to marry William Harding, whose sister was Rachel Harding Overton, mother of the other Jacob Dickinson. Let’s wallow in this convoluted mess, for just a second. Andrew Jackson’s wife’s sister-in-law’s family (let’s call them Dickinson 3) lived next door to the Philipses and were close enough to them that they named their daughter after the women in the family. And Milbiry Philips grew up to become Jacob Dickinson (from Dickinson 2)’s wife’s aunt.

This isn’t a family tree so much as a family briar patch. But we have to remember that Nashville was a small town back then. You only had so many people to marry.

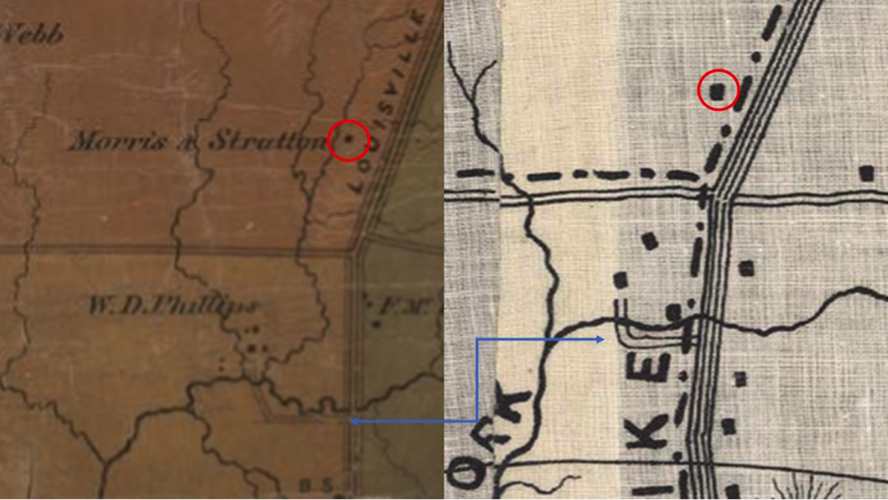

OK, so we know the Philips family owned Sylvan Hall because we know from old maps where William D. Philips lived in what is now Bellshire. According to family lore (which is somewhat backed up by old maps), the Philipses owned everything south of Old Hickory (I suspect actually Bell Grimes), north of Briley, east of Brick Church Pike and west of Dickerson Pike. This would put the Dickinson family land up where the Jack in the Box, Sonic and haunted house are, across from Cedar Hill Park. If you look at this map, that would make the old Dickinson place what is marked Morris & Stratton. In the mid-1800s, Morris & Stratton was the grocer in Nashville. My guess is that they bought the Dickinson land to grow produce for the store downtown.

In the June 19, 1833, edition of the National Banner and Nashville Daily Advertiser, we learn that William D. Philips — who says he is living on the east fork of Dry Creek, seven miles north of Nashville, “near Dickerson’s meeting house” — has found a black filly (p. 3). I think what this tells us is that the meeting house had to be very close to William’s house, in order for it to be a good landmark. Probably, if you saw the meeting house, you could see William’s house, which means that you could probably also see the meeting house from William’s house.

I couldn’t verify exactly where William’s house was, but I went to the family cemetery on Oxbow Drive to see what I could see. White family cemeteries tend to be near plantations’ main houses, so I figured it would at least give me a general idea. It took me some time to find the Philips family cemetery, since it’s barely visible from the street, back behind some houses, up a hill. I tried to be as conspicuous as possible — bright-yellow shirt, orange jacket, loud grunting and oh-my-ing — so that the owners of the driveway I was going up, should they be home, would assume that I was what I was: some middle-aged woman looking for the cemetery. I also had the benefit of having the same last name as the people in the cemetery, albeit with an additional L.

No one minded that I was there. Even now, with all the houses and the businesses, the view is breathtaking. You can easily see out to Dickerson Pike, even though you are quite a way from it. And most importantly for this discussion, you can see the Jack in the Box sign very clearly.

If that were all pasture or cropland, you could see the corner, no problem. And anyone at the corner could see the house, if it was up there by the cemetery. Since I could see the Jack in the Box sign from the cemetery, I’m tempted to believe that the Dickinson Meeting House might have been there, or if the northernmost boundary of Philips land was indeed Bell Grimes and not Old Hickory, it could have been at the Walgreens.

However, there’s another possibility that shows up on maps. Take a look at this map from 1871 or this map from 1898. Depending on how tech-savvy Patrick is*, maybe he can even stick this mash-up I made in here for ease of discussion.

The blue line is showing you the same lane leading to the Philips house. And on both maps, there’s a dot near the road up in the old Dickinson property. It could be the old Dickinson house, but if you look on the terrain map on Google or just drive out there yourself, you’ll see there’s another low hill on the other side of the creek, very similar to the beautiful setup the Philipses had. That seems like a more likely location for a house.

But on a flat spot with plenty of places to put wagons and horses? A place that might flood and it’s not the end of the world? That seems like a likely location for a meeting house. I measured the distance from the creek south of the Philips house to Bell Grimes Road, since those are both recognizable landmarks in the past and still basically in the same place in the present. They are also about as far away from each other as the mystery dot is from Bell Grimes.

The distance from the creek to Bell Grimes is just under half a mile. The distance from Bell Grimes to the mystery dot, then, is about a half a mile. If the mystery dot is the old Dickinson Meeting House, then the location was about where that haunted house, the Beast House, is now.

Since I’m not an archaeologist, I didn’t start digging in their parking lot looking for ... what, exactly? Old hymnals? A crude lectern? Ancient casserole dishes? I have no idea what kinds of items you’d find that would verify the presence of an old church. I guess possibly antique tiny glass communion cups? Maybe I should grab a couple of teenagers and see if they start complaining “but it’s so boring” the closer and closer we get? Could I use teenage antipathy for going to church as a kind of divining rod for the location of the old meeting house? Either someone’s going to have to find something — a map, a will, an old deed — that would tell us the exact location of the old meeting house, or I’m going to have to do some unethical human-experimentation archaeology.

Or, you know, I guess I could be satisfied that we have gone from knowing that there was a meeting house out there, somewhere, between the Cumberland and Goodlettsville, to having narrowed down the location to a half mile on the west side of Dickerson Pike north of Bell Grimes.

But this does raise the question: If Dickerson is just a spelling error, why don’t we fix it?

*Editor's note: Piece of cake.