@startleseasily is a fervent observer of the Metro government's comings and goings. In this column, "On First Reading," she'll recap the bimonthly Metro Council meetings and provide her opinions and analysis. You can find her in the pew in the corner by the mic, ready to give public comment on whichever items stir her passions. Follow her on Bluesky here.

Mayor Freddie O’Connell has been on a press tour.

He’s been extolling the virtues of Fusus — a software platform that collects and integrates data from a variety of sources, including private surveillance cameras, for use by law enforcement — to anyone who will listen. But granting the Metro Nashville Police Department easy access to a network of private surveillance cameras is the kind of “security theater” then-Councilmember O’Connell warned us about during discussions of license plate readers.

O’Connell has crafted a narrative to explain his apparent about-face on the issue. He and his legislative affairs director Dave Rosenberg — another longtime critic of mass surveillance — have dismissed concerns from residents and councilmembers who worry that this type of technology, like the license plate readers they both vigorously opposed while serving on the council, could be used to target vulnerable groups.

Surveillance camera network bill advances to final reading

In an interview with the Scene’s Eli Motycka, O’Connell suggested that we all chuck our phones in the Cumberland River if we’re so concerned about being constantly monitored. Where is the man who, citing an investigative series on New Orleans’ surveillance apparatus — which includes the type of “real time crime center” and video feed integration O’Connell now supports — encouraged Nashvillians to “not let fear drive Nashville to follow New Orleans’ path”?

“We can build safer communities through smart, strategic investments that don’t involve spying on one another,” O’Connell tweeted in 2021.

According to Rosenberg, interviewed last year by the Nashville Banner’s Stephen Elliott and Steven Hale, the police would not be able to access any cameras without a call for service. Rosenberg conveniently omits the fact that police officers themselves can initiate calls for service. And in a state where local law enforcement can be compelled to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement officials, it’s easy to imagine a universe in which local law enforcement is pressured to initiate investigations on behalf of the feds.

In that same interview, Rosenberg said, “Fusus is not built to be a real-time monitoring of video tool.” Tell that to the residents of government-subsidized housing complexes in Toledo, Ohio, where police spent more than 18,000 hours livestreaming video last year using Fusus.

O’Connell has maintained that Fusus doesn’t create or store data, but the contract the council rejected last year lists the full scope of services the MNPD planned to use — that scope included fūsusVAULT, an “evidence vault for the storage of all videos and still images” captured through public and private video feeds.

I could go on, but honestly, this game of Whac-A-Mole is exhausting. Every new statement coming out of O’Connell’s office — often parroted by pro-surveillance councilmembers — brings with it a new contradiction. The problem with Fusus, as with all surveillance systems, is that you can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube. Once you set up a system like this, you can’t control what it’s used for, no matter how many “guardrails” you put in place.

Mayor, a longtime police skeptic, now favors video surveillance tool as it heads toward a council compromise

First-term Councilmember Rollin Horton seems convinced that his bill to establish these so-called guardrails will protect Nashvillians from state and federal overreach. I consider that a delusional take on the power of local governments. And if the past is prologue, passage of the bill will only make it easier for O’Connell to push a new Fusus contract through. As they did with license plate readers, councilmembers who might have been on the fence before are likely to use this legislation as proof that they’ve adequately addressed the community’s concerns.

Horton is playing checkers, while O’Connell and Rosenberg play chess.

Horton’s bill passed on second reading Tuesday night, with several amendments. The council will consider the amended bill on its third and final reading at the next council meeting, March 18. There’s no public hearing on the bill, so residents interested in sharing their thoughts should contact the council or sign up for the time-limited public comment period.

I Really Don’t Care, Do U?

The council will have a public hearing on a bill to move the Metro Historic Zoning Commission staff to the Planning Department. In response to public dismay, the council made the unusual move Tuesday night to schedule a public hearing on this bill — which otherwise wouldn’t have required a hearing — for the March 18 council meeting.

It’s hard for me to conjure up much concern about this bill. I’m not particularly wedded to old buildings, and frankly, it feels silly to worry about a bureaucratic reorganization when we’ve got neighbors who are scared to leave their houses for fear of being swept up in a wave of mass deportations.

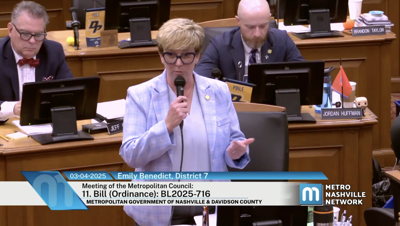

But the council insists on spending hours debating this thing, so I have no choice but to tell y'all about it. Bill sponsor Councilmember Emily Benedict’s original proposal would have moved both the Metro Historical Commission staff and Metro Historic Zoning Commission staff to the Planning Department. For reasons I don’t quite understand, people freaked out about that prospect. Councilmember Burkley Allen called the bill in its original form “terrifying.” I only wish Allen were more terrified about Nashville’s rapid descent into a surveillance state.

Following an audit, new legislation from Councilmember Benedict aims to move MHZC into the Planning Department

Benedict proposed a substitute bill that removed the Historical Commission from the proposal. The council approved Benedict’s substitute, along with two amendments, on second reading. Hancock made an unsuccessful attempt to defer second reading of the bill to March 18, to track with the scheduled public hearing.

Proponents of the bill opposed the deferral. They warned that any delay would result in the state legislature advancing a bill to strip the Historic Zoning Commission of its regulatory authority over buildings in the tourism development zone, a 1,800-acre swath of land surrounding the Music City Center.

Councilmember Clay Capp encouraged his colleagues not to act out of fear for what the state legislature might do. “That’s the oldest trick in the book,” Capp said. “If we go along with that tonight, we’ve advertised that you can do that on any issue you want to.”

Capp has a point. The council has faced threats from state lawmakers in the past, and they’ve been loath to capitulate. So it’s hard to believe that the specter of state preemption is really the driving force behind the legislation.

Councilmember Brenda Gadd, whose district contains nearly a quarter of the city’s historic overlays, expressed her own skepticism. She said the mayor’s office has been aware of “issues arising from downtown” for more than a year, implying a manufactured crisis that could have been addressed before the recent urgency set in.

We’ll probably never know why this is actually happening. It is certainly possible that the seemingly innocuous transfer of the Historic Zoning Commission staff to Planning is some elaborate plot to blunt the commission’s authority and derail historic preservation efforts. But again, with all the shit going down right now, I’m finding it difficult to care about an issue that seems to mainly worry people who live in disproportionately white and wealthy districts.

With limited emotional bandwidth, I choose people over buildings. So sue me.

Bailing out the State

Speaking of lawsuits, the council approved a resolution for a $193,000 settlement of the Nashville Community Bail Fund’s lawsuit against Criminal Court Clerk Howard Gentry without discussion Tuesday night. The NCBF sued Gentry several years ago, challenging a 2008 local rule that requires criminal defendants to allow garnishment of their bail deposits to satisfy any fines, fees, court costs or restitution owed.

The criminal court clerk is a state constitutional officer, which means he essentially serves as an arm of the state. A federal district court confirmed this, and Metro’s legal department in turn attempted to wrangle the state into defending Gentry. The state refused.

NCBF prevailed in the lawsuit. Metro Legal sued the state in federal court, arguing that the state, not Metro government, should be responsible for the costs of the lawsuit, but the court dismissed the case for lack of jurisdiction.

With its attempts at legal recourse exhausted, Metro Legal recommended that the council approve the settlement in hopes of avoiding further costs. You can almost hear the despair in the written analysis: “The Department of Law is not aware of further legal avenues to compel the State to pay the judgment.”

They tried their best, but the state won out. Perhaps councilmembers should take this as a lesson about the relative powerlessness of local governments ... *cough* Fusus *cough*.