@startleseasily is a fervent observer of the Metro government's comings and goings. In this column, "On First Reading," she'll recap the bimonthly Metro Council meetings and provide her opinions and analysis. You can find her in the pew in the corner by the mic, ready to give public comment on whichever items stir her passions. Follow her on Twitter here.

All eyes were on Sandy Ewing Tuesday night. The District 34 councilmember’s vote would likely determine the outcome of a resolution to extend and expand the Metro Nashville Police Department’s contract with Axon for the Fusus platform.

In the days leading up to Tuesday’s Metro Council meeting, Mayor Freddie O’Connell’s office initiated a full-court press on undecided councilmembers, urging them to approve the resolution. Lobbyists from Axon and allied organizations, like the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce, worked to convince undecided councilmembers that Fusus was an unqualified good — a necessary component of 21st-century policing.

Nearly every councilmember was locked in ahead of the meeting.

Ewing hadn’t made up her mind yet. A soft-spoken, bighearted mom, Ewing has at times voted to the left of her disproportionately white and wealthy district. Support for Fusus from outspoken constituents might be enough to outweigh her concerns about the contract.

A Sea Change

Both proponents and opponents of Fusus had a narrow path to victory on Tuesday night, and everyone knew it.

“That was the tensest night since I’ve been on council,” recalls Councilmember Jordan Huffman, a staunch supporter of Fusus. “Not even close.”

As the council meeting got underway, Ewing’s seat was conspicuously empty. She was nowhere to be found. As it turns out, Ewing had nearly collapsed in the tunnel on the way to the meeting. “I had spent a lot of time researching and had come to the conclusion that my vote at this moment had to be no,” she says. “As I approached the council chambers, I had an unexpected health event. I debated whether to stay, knowing how divided we were and how close this vote would be.”

Split Metro Council rejects video integration technology by one vote despite plea from mayor

Ewing made the difficult decision to leave the courthouse and miss the meeting. That could have spelled disaster for the anti-Fusus coalition.

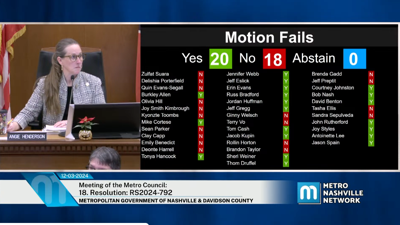

But just before the meeting was called to order, a message began to circulate — first among councilmembers, then among residents in the gallery: Because it was a sole source contract for over $250,000, the resolution would require 21 affirmative votes to pass.

All of the vote counting and machinations in the weeks leading up to the vote, from proponents and opponents of Fusus alike, had revolved around the idea that a resolution requires a simple majority of the members present and voting to be approved. The 21-vote requirement was a welcome gust of wind in the opponents’ sails.

“With the 21-affirmative-vote requirement, the chances of it passing fell dramatically,” says Councilmember Rollin Horton, who voted against the resolution. “The proponents would need to win every swing vote for it to pass.”

Spirits were cautiously high among those who hoped to defeat the resolution. By most counts, even with Ewing absent, the pro-Fusus contingent did not have the votes to get to 21.

‘We’ve Lost Antoinette’

Then, another message, this one alarming for the anti-Fusus coalition: “We’ve lost Antoinette.”

A member of the minority caucus, Councilmember Antoinette Lee — who could not be reached for comment — had been a solid no vote. When the public comment period concluded, a pro-Fusus speaker approached Lee for a brief conversation. Shortly thereafter, Lee’s solid no turned into a solid yes.

“That raised the stakes of it significantly,” recalls Horton. With Lee in the yes column, opponents of the resolution couldn’t afford to lose a single other vote.

Councilmember Tasha Ellis was prepared to vote in line with the minority caucus to reject the resolution. At some point during the meeting, though, she flipped. Ellis would be the 21st affirmative vote needed to approve the contract.

With minutes to go before the vote, Councilmember At-Large Zulfat Suara vacated her seat at the front of the chamber, making her way to the back row, where Ellis sits. Suara made a personal appeal to Ellis, urging her to vote against the resolution.

“I thought we had the votes,” says Huffman, who describes Ellis as an essential part of his attempts to “build a new coalition on the floor.”

“I thought we had them. And Tasha Ellis flipped at the last minute. Zulfat walked back, said something to her, and that was it.”

Ellis’ no vote was the final nail in the coffin. Fusus was dead.

A Tactical Error

The resolution might well have passed, if not for a deferral at the last council meeting. By deferring the resolution, opponents gained a net-three vote advantage. Councilmembers Brandon Taylor and Delishia Porterfield — both no votes — were absent at that meeting. And Councilmember Jennifer Gamble — an almost certain yes vote — was present.

Assuming everyone else would have voted the way they ultimately did on Tuesday, the pro-Fusus crowd had the votes to approve the contract at the last meeting. Huffman knew that. It’s why he was the only pro-Fusus councilmember to vote against the deferral last month. But the administration wanted the deferral, so they could make the proposal more palatable with contract amendments they said would insulate the city from state and federal interference.

Suara, a steadfast opponent of government surveillance, aptly described the updated proposal as a “feel-good substitute,” designed to “make people think we’re doing something.” To many councilmembers, no amount of amendments or assurances could overcome the real and present danger of government overreach.

Huffman thinks the fear of President-Elect Donald Trump’s plans to terrorize marginalized communities sank the resolution. “I think Fusus would have passed if the presidential election would have gone the other way,” Huffman says. “I truly, truly believe that.”

Under Pressure

I’ve been a registered lobbyist on two occasions. The extent of my lobbying career, if you could call it a career, has included a presentation to the Board of Zoning Appeals and helping schedule a community meeting for a proposed development.

I am no James Weaver.

In my admittedly limited experience, though, the idea of threatening elected or appointed officials simply never occurred to me. I’ve always believed that if I just make my best case, the decision makers will consider the proposal on its merits. Maybe that’s naive. Maybe it’s why I’ve had a grand total of two clients. Maybe it makes me ineffective, but it seems to me that this is how government should work.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with being paid to advocate for a client, but how you advocate matters. Heavy-handed tactics can easily backfire.

A councilmember who preferred to speak anonymously says two of Axon’s lobbyists threatened retaliation for a negative vote. If the councilmember voted no, the lobbyists said they would pull support for the councilmember in future elections and recruit candidates to challenge them.

“I was really shocked,” says the councilmember. To them, it seemed to be a case of cutting off your nose to spite your face. These lobbyists have a lengthy list of other clients who will undoubtedly require their services to lock in support from these very same councilmembers. “Maybe it was just out of desperation,” the councilmember posits, noting that the ham-fisted approach to scare them straight only strengthened their resolve to oppose the contract. “I knew I was on the right track.”

Other councilmembers received threats of their own — not just to their reelection prospects, but also to future legislation they hope to pass and bids for elected committee chair positions. One lobbyist allegedly vowed to “destroy the progressives.” The lobbyists appear to have misread the weight of their threats. But I think shedding light on their approach to wielding their power tells us something important about what councilmembers are up against when they decide to vote their conscience. From the outside looking in, it’s hard to understand the level of pressure they face on a vote like this one.

A certain amount of fluidity is necessary when weighing a consequential vote; locking in too early can mean missing out on late-breaking information or failing to fully consider the implications of a vote. Holding space for that uncertainty makes councilmembers a target of exhausting pressure campaigns.

We have some very conscientious councilmembers who are trying to balance all manner of competing interests while under intense scrutiny. That’s tough. They’re human.

I think we could all do more — myself included — to keep that in mind. Now, I’m not suggesting you should let them off the hook when they disappoint you. They were elected to represent you; you deserve to be heard. But when the other side is holding a flyswatter, a little honey goes a long way.

People Power

The effort to kill the Fusus contract was not spearheaded by councilmembers. Even some of the most outspoken progressives waffled in the weeks leading up to the vote. Porterfield said as much on the floor Tuesday night.

Rather than leading the charge to make the public case against Fusus, councilmembers relied on a hodgepodge group of community members to press the issue. Councilmembers didn’t turn out 41 people to speak against Fusus. That was the work of unpaid organizers. In a matter of weeks, an informal network of community activists formed an ad hoc collective. They rallied the opposition in group chats and email lists across the county. They even created a zine outlining the dangers of Fusus.

Sympathetic councilmembers needed hand-holding to ensure they didn’t waver in their resolve. Those on the fence needed messaging tailored to their specific motivations.

Three forms of police technology raise questions about privacy and public safety

Opponents of Fusus took time away from their paying jobs, their families and their free time to fight for their vision of a safer Nashville — a vision that does not include tapping into a citywide private surveillance network.

When it came time to put up or shut up, organizations like the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition offered legitimacy to the case against Fusus, serving as a force multiplier for the cause. Their support countered the institutional heft of groups like the Nashville Downtown Partnership and the Chamber of Commerce, both of which lobbied heavily in favor of Fusus.

The cards were stacked against the opponents. On the other side of the fight were sophisticated lobbyists, the MNPD, and the mayor — who took to social media to extol the virtues of Fusus. O’Connell didn’t just rely on his staff to get councilmembers on board. He made phone calls of his own, an unusual move that demonstrates just how determined he was to get this contract approved.

Opponents pitted themselves squarely against some of the most prominent and successful power players in the city. They endured resistance from the mayor’s office and claims that their fears were based in misinformation. Still, they didn’t waver.

That’s people power.