The Henry Allen and Georgia Bradford Boyd House

The physical devastation of March's tornado and the ongoing economic incertitude caused by the pandemic clearly influenced Historic Nashville in its selection of the 2020 Nashville Nine, its annual list of "historic Nashville properties and neighborhoods most threatened by development, neglect, or demolition."

This year's list also features a number of properties significant to the civil rights movement in Nashville and Black history in the city.

“Nashville has experienced an extraordinarily difficult year between the tornado and the pandemic,” Historic Nashville president Elizabeth Elkins says. “Prior to each, the city’s growth rate made saving historic properties an afterthought. This year, Historic Nashville carefully chose nine properties that reflect those challenges, as well as underscore our strong commitment to the city’s important and long-neglected African American history.”

This year — in addition to working with property owners, government agencies and the public at large to preserve the locations on the list — Historic Nashville is committing $10,000 to preserve the spaces.

Here's the rundown.

Tennessee State Prison

The imposing 1898 Gothic Revival prison on Centennial Boulevard, which closed in 1992, was made famous for its appearances in films like The Green Mile, The Last Castle and Walk the Line. Asbestos and general deterioration put the main entrance off limits for years, but the state-owned facility was still viable for exterior shots for moviemakers; however, March's tornado knocked down roughly 40 yards of the building's west wing. With its stunning facade and hand-cut stone, it echoes a time when aesthetics and thoughtful construction were considerations for civic structures — even prisons. Historic Nashville concedes that the tornado damage may make it impossible to save the entire structure, but the organization wants to work to save as much as possible.

The Henry Allen and Georgia Bradford Boyd House

The Boyds were central figures in Nashville's Black community in the first half of the 20th century. Henry Allen Boyd was the publisher of The Nashville Globe, an influential newspaper in the Black community, president of Citizen’s Bank and founder of the National Baptist Publishing Board of the National Baptist Convention of America. He was a Fisk trustee — the university owns the home on Meharry Boulevard — and helped lead the charge to bring Tennessee State University to Nashville. His wife Georgia fought for both gender and racial equality in the city through her involvement in numerous civic organizations. The house, built in the 1930s, was designed by McKissack & McKissack, the first Black-owned architectural firm in the country.

Fisk pulled a permit to demolish the home earlier this year, but that action was stopped via a petition started by TSU history professor Dr. Learotha Williams, as detailed in our Sept. 24 cover story.

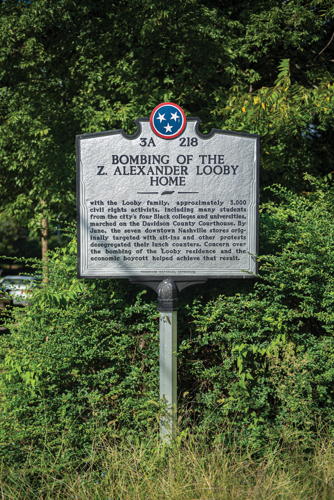

Z. Alexander Looby House

The still-unsolved 1960 bombing of attorney Looby's home, also on Meharry, was a critical moment in the civil rights movement both in Nashville and in the country at large. While the home was originally white clapboard, Looby had it encased in brick, likely as a precaution against bombing attempts. Other features designed to foil terrorist attacks are the home's unusual windows, which are narrow and elevated. Looby also had the front door moved from the side of the house facing the street to the driveway to make it difficult for malefactors to sneak up on the home.

Though historically significant because of its role in the struggle for civil rights and architecturally significant as an example of adaptations made to protect its occupants, the home is in a state of disrepair and off limits to the public.

El Dorado Motel Sign

Universally regarded as "rad," the colorful sign for the El Dorado Motel at the corner of Buchanan and Ed Temple is all that remains of the lodging that opened in 1957, owned by restaurateur George Driver and grocer Bill Otey, prominent Black business owners. Singer Harry Belafonte and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were to stay at the hotel in 1961 when they were scheduled to be in town for a concert and fundraiser for the Nashville Christian Leadership Council at the Ryman Auditorium. Belafonte, however, fell ill and had to be hospitalized, and the concert was canceled. Ted Rhodes, the first Black pro golfer and namesake of the neighboring park and golf course, lived in the motel at the end of his life.

Hopewell Missionary Baptist Church

Hopewell Missionary Baptist, which has stood at 10th and Monroe since 1906, lost its steeple and much of its sanctuary in the March tornado. It's the second time the bell tower felt nature's wrath, as it was also destroyed in the May 1999 tornadoes.

The church is an important structure in the history of both the Black and German communities in Nashville. Designed by Swiss-born architect Henry Gibel, it was originally the home of Third Baptist Church. Third moved out in 1959, selling the building to Hopewell, which had split from Mt. Zion Baptist in 1914.

Chaffin's Barn

The dinner theater on Highway 100, which opened in 1967, was Nashville's first professional theater. Originally part of a nationwide dinner theater franchise, the Chaffins kept the theater running after the parent company folded in the 1970s. But the pandemic proved too much of a burden. Historic Nashville says "the closing of [entertainment] businesses also creates uncertainty for the buildings housing them."

The Barbizon Apartments

Vanderbilt University acquired the modernist Barbizon in 2000, and the university's long-term growth and infrastructure plan calls for its demolition as part of the construction for its housing village for graduate and professional students. Vanderbilt has already torn down properties near the Barbizon as part of the project, including an entire block of Broadway between 20th and Lyle. "Historic Nashville urges Vanderbilt to choose a path for developing this stretch of Broadway that preserves it character instead of razing it," the organization says.

The Firestone Building

At the flatiron between West End, 25th Avenue and Elliston Place, the unusual Firestone Building was, as its name indicates, originally a tire and auto shop. The Art Deco structure was designed by the same architects who designed the downtown post office, now the Frist Art Museum. After Firestone moved out in the 1980s, a rotating cast of pharmacies occupied the main building. Both that building and the smaller corner building are currently on the market. Because of its location, Historic Nashville is concerned it may be lost to development.

William Edmondson Headstones

Outsider folk artist William Edmondson was the first Black artist to have an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, but Nashville is the home to his most accessible works: dozens of headstones in Black cemeteries in Davidson and Williamson counties. Edmondson carved the headstones for his friends and family, and most feature animal sculptures — Edmondson called them "critters" — and the distinctive Edmondson lettering.

Years of neglect, plus theft due to Edmondson's prominence, threaten the headstones. In fact, only three still have the critters. Historic Nashville is urging stakeholders to come together to protect the headstones.