This story is a partnership between the Nashville Banner and the Nashville Scene. The Nashville Banner is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization focused on civic news. Visit nashvillebanner.com for more information.

Lisette Monroe and Harold Wayne Nichols have been here before.

In July 2020, Nichols was less than three weeks away from being strapped into Tennessee’s electric chair for the 1988 rape and murder of Monroe’s then-21-year-old sister, Karen Pulley, when Gov. Bill Lee called off the execution. Thirty years after Nichols received his death sentence, the global COVID-19 pandemic prevented it from being carried out.

“I thought finally I could go to Karen’s grave and say, ‘It’s over,’” Monroe told the Associated Press.

Harold Nichols will not be executed on Aug. 4, or any time this year.

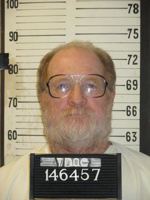

More than five years later, Nichols is due in the execution chamber again, and an intervention of that kind is unlikely. He is set to be killed by lethal injection on Thursday morning and neither the governor nor the courts have given any indication that they are inclined to stand in the way.

Monroe will be in Nashville, although she told the Associated Press last week that she was undecided about whether she will witness the execution. She’d planned to talk to the Banner, but later decided against it. The swelling media attention had become emotionally overwhelming, she said. On Facebook, she asked friends and family to join her in celebrating her sister Karen by sharing favorite memories.

Nichols has never denied that he is the cause of the Pulley family’s bottomless pain, that he committed horrific crimes decades ago. After he was arrested in January 1989 for raping four women in the Chattanooga area, he confessed to those attacks. He also admitted that he had broken into Pulley’s home months earlier and raped her before hitting her over the head with a wooden board. Although a roommate found her alive, according to court documents, she died the next day. Nichols later pleaded guilty to felony murder, aggravated rape and burglary. The jury sentenced him to death, although six jurors are quoted in Nichols’ clemency application saying they either would have chosen life without the possibility of parole if it had been an option at the time or have changed their mind about the death sentence since.

“I wish that there was something I could do to change the things that happened,” Nichols said during his sentencing hearing, according to trial transcripts cited by his attorneys in his clemency application. “I know that all these families and friends are hurting. I know Miss Pulley’s family is hurting. And I’m not asking [them] for forgiveness. I don’t expect that. But if I could change places with Karen I would.”

Forgiveness was offered nonetheless by Pulley’s mother, Ann Pulley, who asked to meet with Nichols after his sentencing. She visited him twice more in the county jail and gave him a Bible in which she had inscribed “presented ... by Karen’s mother with prayers for your salvation” and underlined some of her daughter’s favorite verses.

In a video produced by his attorneys and released along with his request for clemency from the governor, Nichols — now just weeks shy of 65 years old — holds that same Bible and struggles to speak about what it means to him.

“Ms. Pulley didn’t know just the effect that would have on me … not just that day but today,” he says, removing his glasses and wiping tears from his eyes.

His attorneys have said that Nichols — who they know by his middle name — is a perfect candidate for clemency precisely because he is not innocent. Rather, they say, he is guilty and repentant.

Working against the clock, attorneys wage a multifront campaign against the state and Gov. Bill Lee

“Clemency is for mercy,” Deborah Drew of the Tennessee Office of the Post Conviction Defender says in a written statement to the Banner. “Wayne deserves mercy for taking responsibility for his crimes early on, expressing his deep remorse and apologizing to the Pulley family and the other women he sexually assaulted, and taking Mrs. Ann Pulley’s grant of forgiveness to heart, which set him on this 35-year path of atonement.”

Commuting his sentence to life without the possibility of parole, Drew adds, would also be in line with the position prosecutors took in 2018 when they agreed to that sentence before a judge rejected it.

Nichols’ path of atonement, his attorneys write in his clemency application, has included becoming a leader and a peacemaker on death row, assisting prison staff as a maintenance worker, participating in philosophy and divinity classes with Vanderbilt University students and mentoring at-risk youth in a writing program.

Nichols’ attorneys also write about the torturous boyhood that came before he became a man with so much to atone for. His father was “a violent, intimidating, and profoundly mentally unhinged man who terrorized his family” with physical, sexual and emotional abuse. His mother died of breast cancer when he was 10 years old, after which that abuse intensified. Leaders at the family’s church threatened to report him if he didn’t give up the children. Nichols and his sister were then moved to a church-run orphanage, which only turned out to be a different kind of hell.

That’s also how Monroe has described what she and her family have been living through for 37 years since her sister’s murder. Whether the death of the man whose crimes dragged them there can bring them out will be determined in the years to come, away from the courts and the media.

Nichols has been on death watch since Thanksgiving morning in accordance with the state’s new lethal injection protocol, which calls for a 14-day isolation period before an execution. His attorneys are appealing a federal judge’s recent dismissal of his legal challenge to that protocol, which relies solely on pentobarbital. That’s the same drug Tennessee used to execute Oscar Smith and Byron Black earlier this year, the latter of which went painfully awry.

Barring last-minute legal success on that front, or a change of heart by the governor, Nichols will move next to the death chamber.

This article first appeared on Nashville Banner and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.