This story is a partnership between the Nashville Banner and the Nashville Scene. The Nashville Banner is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization focused on civic news. Visit nashvillebanner.com for more information.

On the last night of her life — March 27, 1988 — 29-year-old Angela Clay finished a Sunday shift as a lab worker at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Leaving the hospital around 10 p.m., she found her boyfriend, Byron Black, unexpectedly waiting to give her a ride home.

Their relationship had not been a peaceful one. On the night he came to pick up Clay from work, Black was on a weekend furlough from the Metro Workhouse, a former Nashville jail facility. He’d been serving a two-year sentence there for shooting Clay’s estranged husband — and the father of her two daughters — Bennie Clay during an altercation. According to court documents, Black had once kicked in the front door of Angela’s apartment after she refused to let him in. Family members later told police that she had been talking about reconciling with her husband and that Black had threatened to “pull a Sterling Gray” if she went through with it. Gray was the disgraced Davidson County Criminal Court judge who had killed his wife before shooting himself after she left him earlier that year.

Media reports and court documents from the time reflect slightly different versions of what might’ve happened after Clay left work that night. At some point after seeing some of her family, Black and Clay ended up together with her two daughters, 9-year-old Latoya and 6-year-old Lakeisha. The couple had been seen arguing in preceding days, and one of Clay’s neighbors reported hearing a series of loud bangs coming from her apartment between 1 and 1:30 in the morning.

The following evening, after police were called to the South Nashville apartment by concerned relatives, they found Angela shot to death in her bed. Her older daughter Latoya was dead in the bedroom with her, shot through the neck and chest. The other child, Lakeisha, was lying facedown in a separate bedroom with two gunshot wounds.

Smith, who was convicted of the 1989 murders of his estranged wife and her two teenage sons, was put to death by lethal injection Thursday morning, marking the return of the state’s death penalty

Black denied carrying out the massacre but offered shifting alibis. In an initial interview, according to court documents, Black told detectives that he had dropped Angela and the girls off with her mother before going to his own mother’s house and staying there for the rest of the night. He returned to the Metro Workhouse shortly after 5 p.m. Monday, several hours before the bodies were discovered. In a second interview the same day, with Black’s defense attorney present, he said that he had gone to Angela’s apartment that Sunday night and discovered the bodies inside before leaving in a panic.

Black was arrested two weeks later after state ballistics experts said a bullet removed from Bennie Clay’s shoulder — which had been lodged there since Black shot him the year before — was fired from the same gun used to kill Angela Clay and her daughters.

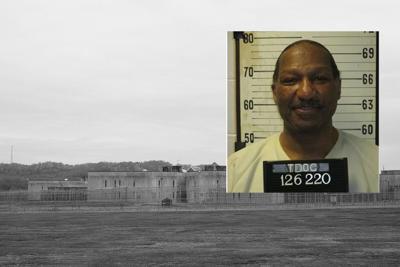

A Nashville jury convicted Black and sentenced him to death in 1989. Now more than 35 years later, he is set to be killed by lethal injection on Tuesday by executioners at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution.

In March, after the Tennessee Supreme Court set execution dates for Black and several other death row inmates, Bennie Clay talked to The Tennessean about his daughters, who would be 46 and 43 years old today.

“My kids, they were babies,” he said. “They were smart, they were gonna be something. They never got the chance.”

Clay has told reporters he plans to attend the execution, but reached by the Nashville Banner over the weekend, he said he did not want to discuss the case — or talk about his wife and daughters — any more until it’s done. He and other family members have seen Black scheduled for execution twice before over the past five years, only to see those dates moved — first due to the COVID-19 pandemic and then because of problems with the lethal injection protocol. But this time, without an 11th-hour stay from the United States Supreme Court or an intervention from Gov. Bill Lee, he seems unlikely to stay out of the death chamber.

Black’s IQ

The state will resume executing people on death row using the single drug pentobarbital

Although Black has maintained that he did not kill Angela, Latoya and Lakeisha Clay, the legal fights and public debates about his case have not revolved around guilt or innocence. His pending execution has raised multiple ethical questions provoked by the death penalty — in particular, how to determine a person’s culpability for heinous acts, at the time or decades later, and what constitutes a humane punishment when applied to a convicted killer.

Over the past month, as his execution date approached, Black’s attorneys have emphasized in court and in the media his well-documented intellectual disability. If he were on trial today, they’ve noted, he would not be eligible for the death penalty. Far from a last-minute legal Hail Mary, attorneys representing Black have been making that argument as long as courts have been considering his case.

Defense attorney Ross Alderman argued in 1989 that his client was not competent to stand trial. In a sworn declaration submitted along with Black’s application for clemency from the governor last month, Alderman said that his then-client was “delusional about what was going on” and “lacked the ability to process” the court proceedings. After Black went to prison, multiple tests administered between 1993 and 2021 found his IQ to be below 70.

In recent years, there has been little argument about his intellectual condition. In 2022, attorneys for the state stipulated in a court filing that Black would be declared intellectually disabled if a new hearing were held today. For the same reason, Davidson County District Attorney Glenn Funk asked a judge that year to vacate Black’s death sentence. But because Black had already lost that argument in court more than 20 years ago — under a standard the state has since updated — judges have ruled that Tennessee’s current intellectual disability law does not apply to him.

Black is now 69 years old, and his intellectual capacity has been further diminished by dementia, his attorneys say. But he is also in declining physical health.

His attorneys have written in court filings that he has end-stage kidney disease and congestive heart failure. In response to his heart condition, doctors placed an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in his chest last year, designed to shock his heart repeatedly if necessary to restore its normal rhythm. In June, his attorneys asked a judge to order prison officials to arrange for medical professionals to properly deactivate that device right before his lethal injection to prevent him from experiencing a prolonged and torturous death.

With new lethal injection protocol in place, state Supreme Court sets new slate beginning in May

Although a Nashville judge initially ordered just that, the state appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which ruled last week that Black can be executed with the device still active in his chest. According to expert testimony in the lower court, this leaves the possibility that the defibrillator will attempt to keep him alive as his lethal injection is proceeding, with each shock amounting to “a kick in the chest from a horse.”

If executioners kill Black with lethal injection on Tuesday as planned, he will be the second death row prisoner executed in Tennessee this year under the state’s new lethal injection protocol using the single drug pentobarbital. Harold Nichols is scheduled to be executed on Dec. 11.

Nationally, Black’s would be the 28th execution of 2025, making this the most active year for America’s death penalty in the past decade.

This article first appeared on Nashville Banner and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.